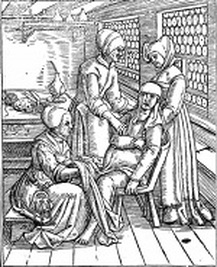

I'm delighted to have Sam Thomas join me on my blog today, talking about death and the seventeenth-century midwife. Sam's first historical mystery, The Midwife's Tale (Minotaur Books, St Martin's), has received great critical acclaim (and I thought it was terrific!). (Check out the interview I did with Sam last year!) His second in the series, The Harlot's Tale, will be out this week and I'm looking forward to getting my copy in the mail! I hope you don't miss out on this great read! Death and the Midwife  A midwife at work A midwife at work When I tell people that I’m writing a series of murder mysteries about an English midwife, I often receive the kind of condescension that people reserve for the very young and the very old. That’s nice, they say with an uncertain smile, not entirely sure that they’ve understood me. Actually, that’s not true. They know they have understood me. They’re just not sure that I’m making any sense. After all, what could midwives have to with murder? Lawyer-sleuths? Sure, we’ll believe that. Crime-solving doctors? Absolutely. But midwives? Yes, midwives. While we (rightly) associate midwives with bringing life in to the world, for several centuries midwives also sent people out. Most obviously, thanks to comparatively high infant and maternal mortality rates, midwives saw their share of death in the delivery room. But this is just the start, for midwives were key players in England’s legal and judicial system, and when a woman came into contact with the law, whether as a victim or a suspect, a midwife often was on the scene. The most common legal task that midwives faced was to discover the fathers of illegitimate children so that they could be made to pay for the upkeep of their offspring. Midwives did this by – to be blunt – threatening the mothers: If a woman refused to name the father of her bastard child (perhaps she had been paid for her silence), the midwife was supposed to withhold care during the birth. “You don’t want to name the father?” she would ask. “Then you’re giving birth alone. Good luck and Godspeed.” (It is not for nothing that I opened The Midwife’s Tale with just this situation.) And while most mothers probably relented, there are cases in which midwives did indeed make good on their threat. In thus was the midwife’s job to expose infidelity and lechery to public view – reason enough for some men to kill, no? More dramatic – and mercifully less common –was the midwife’s role in infanticide investigations. When an infant’s body was discovered, the constable would summon the local midwife and she would search out and interrogate suspects. Imagine the scene from the mother’s perspective: A young woman has given birth to an illegitimate child, and she has done this in secret and by herself. Perhaps the child is stillborn, perhaps not, but the mother panics and abandons the child out of fear of discovery and punishment. Within days or even hours, the midwife arrives with a dozen women in tow. She corners the mother and squeezes her breasts to see if she is lactating. She then insists on examining the mother’s privities (to use the early modern word) for evidence of a recent birth. Then the midwife and her assistants begin to badger the mother in confessing to a crime which had only one punishment: death by hanging. In depositions from infanticide cases, the language of pressing is ubiquitous: “after much pressing, Jane did confess” or “we pressed her further and again, until Jane did confessed.” There were no lawyers, no Miranda rights, just the mother and the women who would not be denied. Such work was not for the tender-hearted. Nor was this all. As the local expert on women’s bodies, it fell to the midwife to examine women or girls who had been raped, and to testify against their assailants. If a woman were sentenced to death and claimed to be pregnant (which would prevent execution), the midwife judged whether she was lying. When a woman was accused of witchcraft, the midwife examined her body for evidence of the Witch’s Mark, where Satan’s imp had suckled. Guilt or innocence lay in the midwife’s hands. Midwives thus dealt in their community’s darkest secrets: adultery, murder, rape and witchcraft were their stock in trade. And in these cases, the midwife’s word determined who lived and who died. What more could you want from a protagonist? (This post originally appeared in Poe's Deadly Daughters and was reprinted with permission by the author). Sam Thomas is an author and teacher living in Shaker Heights, Ohio. The Harlot’s Tale, the second book in the Midwife Mystery series, is on sale now. It’s predecessor, The Midwife’s Tale, is now available in paperback. To find a copy of either book, follow this link. Also, he would be more than happy to visit with your book group, either in person or via Skype.

2 Comments

|

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed