I'm often asked about how I write my books, whether I outline them first or just start writing. But really my books come to me in a series of images and then questions, which I then seek to answer. For A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, the image that came to me is essentially what has been portrayed on the cover. The image was of a disheveled woman, barefoot and clad only in a simple shift, covered in blood that was not her own. In my mind, she had no memory of who she was, or what had happened to her. But that's where the questions started.... First, I needed to think about where Lucy could encounter her that was plausible. I thought maybe on the London Bridge, but the Bridge had been damaged by the Great Fire, and I didn't think Lucy could be walking in that direction. So I thought about other options, and ended up having Lucy encounter the woman on Holborn Bridge, by the rancid River Fleet when out delivering books. Then, I began to think about what Lucy would do when she found the woman--how would she react? Lucy, being Lucy, decides that she can't just leave this poor afflicted woman to the devices of suspicious townspeople, and takes her to a physician she knows. And then that led to more questions. What would a more educated person think about the woman's illness? What kind of healed wounds might the woman have, under closer inspection? How could they learn the woman's identity--what kind of clues could be on her person? And of course lastly--whose blood was on the woman? Those are the types of questions that I would ask myself, to keep my story moving forward.... If you are interested in reading an excerpt, you can see how these questions involved into the story at the heart of A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET.

0 Comments

Probably one of the most frequently asked questions I get from people seeking to write historical fiction is this: How much research should I include in my historical novel? And my reply, which may sound more flippant than I intend, is just this: Enough to tell the story. I've written elsewhere about balancing historical accuracy and authenticity. So, I thought today I'd given an example of how I seek to have my characters interact with historical details, hopefully without just dumping my research on my readers. I could have picked any passage, but in honor of Easter, I picked an excerpt from my forthcoming novel, A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET. In this, scene Master Aubrey has just returned from selling pamphlets (unsuccessfully) on Maundy Thursday, (known in other parts of the world as "Holy Thursday.") There were a couple of factual details about Easter that I wanted to bring up in the scene. First, since the Middle Ages, there was a tradition in England that on Maundy Thursday, the monarch would give money to the poor and wash the feet of twelve poor people. [Indeed, while the etymology is not certain, the word "Maundy" may have come from the Latin world mendicare ("to beg.")] But we know from the diarist Samuel Pepys, in 1667, King Charles II opted against the practice that year, asking the Bishop of London to do it for him. Second, there had been an ongoing debate about the moveable date of Easter--some scholars of the time insisted that the date should be the same each year, similar to how Christmas was always on December 25. Third, in general, I wanted to allude to the fact that England was on a different calendar (the Julian Calendar) than Catholic nations like France and Italy, which had adopted the calendar created by Pope Gregory (the Gregorian Calendar). I couldn't use all the research I had at my fingertips, but I tried to work in a few of the more salient points within their trade as the printers and sellers of books. So you can see what details I managed to include...  John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 Master Aubrey laid his pack down. “I sold a few. I went to Whitehall to see the King wash the feet of the poor people, but the Bishop of London did it on his behalf.” The printer seemed a bit disgruntled. It had long been the custom for the monarchs of England to wash the feet of twelve men and women, as Jesus had washed the feet of the Apostles before the Last Supper. Having the Bishop of London take on the task instead of the king clearly irked him. Sometimes Lucy suspected the printer had Leveller sensibilities and liked it when the royals took on more mundane responsibilities. “Which pieces did you bring?” Lucy asked, changing the subject. In truth, she was always intrigued to know how the packs got decided. Master Aubrey had a knack for knowing what to sell to attract a crowd that she desperately hoped to learn for herself one day. “Could not very well sell murder ballads and monstrous births on Maundy Thursday, hey? Brought along John Booker’s Tractatus paschalis and John Pell’s Easter Not Mis-Timed. Too many of them, it seems. Only the sinners’ journeys, like the one you wrote about that Quaker, sold today.” He kicked the still-full bag, looking in that moment a bit like Lach, causing Lucy to hide a smile. A rare miss for Master Aubrey. Most people did not care how the date of the moveable holy day was affixed in the almanacs each year. Nor did they care why Catholic nations celebrated Easter and Christmas on different days than they did in England. I'm sure some readers might think that I have provided too much detail here, and other people think I have not offered enough. But, for me, this was "enough to tell the story."

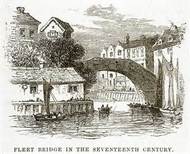

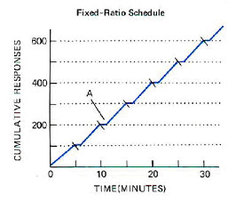

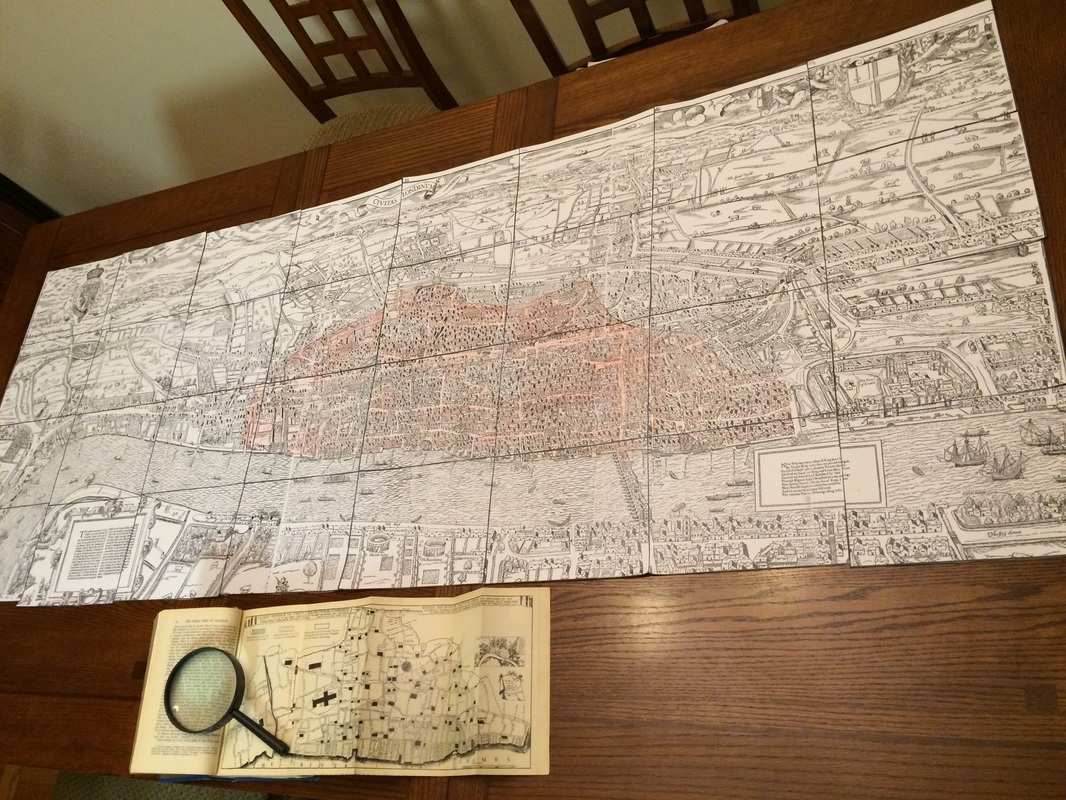

When I first began to conceive of A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET (to be released April 12, 2016!), an image came to me that ultimately informed the entire novel. That image was of a young woman, barefoot and clad only in her shift, stumbling at dawn through the rubble left by the Great Fire of 1666 (and yes, I am counting down to the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire! See counter to the right!) And, of course, I needed her to run into Lucy, so that my intrepid chambermaid-turned-printer's apprentice would have a reason to be involved in the mystery that follows. But it took me a while to figure out exactly where this encounter could reasonably occur. I thought at first the woman could be found on London Bridge. And I really wanted to write something about how the impaled heads of traitors, which lined either side of the Bridge, had caught fire. After all, in Annus Mirabilis Dryden had described in macabre detail how sparks had scorched the heads: "The ghosts of traitors from the Bridge descend, But then when I did a little more digging, I discovered that London Bridge had been damaged in the Fire, and really was not much of a thoroughfare in the months that followed the blaze. Indeed, there would have been no good reason for Lucy to be traveling in that direction, particularly so early in the morning. So I realized that, first, I needed to think through what Lucy was doing out of Master Aubrey's house, just before dawn. Not too hard to figure out actually. She needed to be delivering books. But then the question became, in what direction did she need to travel to deliver those books? Most people were living to the west of where the Fire had stopped. So why would she be going into the wasteland at all? To figure out this challenge, I began to systematically create a large scale map of Lucy's London using photocopies of reconstructed maps of the period. As I marked in red the burnt out area of London, I realized that the Fire line had been stopped to the west along the River Fleet. The River Fleet? This was not a river I knew anything about. A vague recollection that the Romans had used the river to transport goods, but I couldn't remember ever hearing about it otherwise. I became even more curious when I saw that several bridges, including the Fleet Bridge and Holborn Bridge, crossed it. Clearly, the river was wide enough or significant enough to require actual bridges, so it couldn't just be a stream. Intrigued, I began to read more about this mysterious river. From the maps I could see that the river flowed from the north, went through the Smithfield butcher markets, traversed Fleet Street, and emptied into the Thames. There was also a region that surrounded it, awesomely called "Fleet Ditch." [Sidenote: I really wanted my book to be called "Murder at Fleet Ditch," but that title didn't even make it past my editor. A little too stark, I guess.]  By all accounts, by the 17th century, the River Fleet was no longer a river where boats could easily travel, but had instead become a place where people would dump animal parts, excrement, and general household waste. Indeed, Walter George Bill, one of the great original historians of the Great Fire, described the River Fleet as an "uncovered sewer of outrageous filthiness." And yet, there were still accounts of people bathing in its waters (yuck) and even drinking from it (yuck, yuck, double yuck), despite its considerable stench and grossness.  So the River Fleet--and the original bridges that crossed it--formed a natural backdrop for my story. I could not find a picture of the 17th century Holborn Bridge, but I thought this artist's rendering of Fleet Bridge might serve as a model. And because the Holborn Bridge was still in place after the Fire, with the unburnt area and markets on one side, and the burnt out area on the other, it became the perfect place for Lucy to encounter this desperate woman.  My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... But of course, I was still curious...is there still a River Fleet? The answer is, yes, of course, but it was finally bricked over in the 1730s, after being declared a public menace. It was still problematic though, particularly in the 19th century, when a great explosion occurred as a result of the expanding gasses in the pipes below the streets. Raw sewage apparently spilled everywhere!!! (Don't even think I wouldn't use that awesome detail if I ever set a book in 19th century London. But I doubt it would make it to the cover!) And if you want to know more, here is a nice overview of the history of the River Fleet in all its--ahem--glory.  What's he waiting for? What's he waiting for? A few weeks ago, I received my editor's notes for A Death Along the River Fleet. As always, the comments were insightful and thorough, but not particularly hard to address or to think through. And yet I found myself wanting to do anything but sit down and work on them. Everything else was suddenly more immediate, more necessary--organizing a desk drawer, writing a blog post (including this one), and a vast array of other far less important things and activities. Classic procrastination, right?  http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg But why? Why would I procrastinate on a task that I knew I wouldn't mind doing--that I might even enjoy doing? I mean, usually when I procrastinate, its because there's a task looming that I really don't want to do. Like, cleaning the litter box. Pulling weeds in the garden. Other tedious or annoying tasks like that. So why was I putting off a task that I didn't really mind doing? If it's not procrastination, is it simple weariness? Or maybe fatigue? But I didn't really feel exhausted. I mentioned this question to my husband--my alpha reader and in-house cognitive psychologist--because he can offer a psychological explanation for anything that plagues me as a writer (e.g. Me: "Why can't I remember what happens in my books?" Him: "You're not crazy, you're just experiencing proactive interference.") So in this case, he told me that my most recent issue was probably not truly procrastination, but rather something called a "Schedule of Reinforcement." So the schedule of reinforcement goes something like this: Imagine that an adorable little rat with a bright twitching nose is in a box with a lever. That rat is on a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, which just means it will receive a food pellet (reward) after every 100 lever presses. Once the rat begins to press the lever, it will work at a fast steady pace until the food reward is earned (the up slope in the figure below). (So if I'm the rat in this scenario, I've earned my reward--I've sent my book in to my editor and received my edits.) However, once the rat earns the reward, it stops responding for a while (the flat point A in the figure). This is known as either the “post-reinforcement pause” or the “pre-ratio pause.” Essentially, the length of the pause is proportional to the amount of work that was required to get to the reward. The interesting part, he explains, is that, generally, the length of the pause is not due to fatigue. Instead, the rat--or other organism, like a human being--seems to use that time to mentally prepare for the large amount of work to come. He says it’s not fatigue because if you artificially get the organism to begin (e.g., place rat paws on lever so that it depresses), then the organism will go on a “ratio run” and perform the behavior until the next reward is given (even if it just completed a run and had no break). So apparently, this has interesting implications for procrastination with humans. As he explains, research on schedules of reinforcement suggest that the best way for a human to overcome procrastination is to artificially get the human to begin the project. For instance, if a college student has to write a term paper, s/he can trick themselves by saying, “I’m only going to write the first two sentences and then I’ll stop.” Often, once they begin, they go on a “ratio run” and write much more than intended (just like when the rat was forced to depress the lever). So, the takeaway for writers (because this is apparently what happened to me): "When you have to dig back into a project (e.g., edits), it’s probably not fatigue that leads to procrastination. That “procrastination time” is used to mentally gear up for the considerable amount of work to come. Even so, simply starting (e.g., on the easy edits), can lead to a ratio run and solid progress." So a scientific explanation for what we all at heart know is the secret for overcoming procrastination: Get your butt in chair and JUST START....but start with the easiest thing possible. The rest will come. And hey, let me know if you have any other writerly conundrums that you would like a professional psychologist to explain. He can come up with a theory for anything. Just address your query to "Dear Alpha Reader." :-) I think it looks beautiful! Great movement--a fresh direction. Who is that woman anyway..? Why is she running...?

All secrets will be revealed April 2016...!!!  I'm so happy and honored to say that my third historical novel, The Masque of a Murderer, officially launches today, April 14! And while I may not be quite as giddy when my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate (2013) launched two years ago--because nothing can ever compare to the release of a first novel--I'm still as loopy as I was last year, when From the Charred Remains (2014) entered the world. Recently, in preparation for the launch, I've been answering a lot of fun and interesting questions about The Masque of a Murderer (the historical background, the story and characters, and my writing process etc). So, I thought I'd do a quick round-up here! I welcome you to:

Thanks so much for sharing this journey with me!!! And I appreciate all the bloggers and reviewers who hosted me, including those through Amy Bruno's Historical Fiction Virtual Blog Tours! And I'm always so grateful to the wonderful people at Minotaur, especially Kelley Ragland and Elizabeth Lacks, and my agent David Hale Smith, and of course my wonderful alpha reader, Matt Kelley!! (and now, I turn my attention back to A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, due out April 2016!!!!) My fourth book has had several different titles, but none that really resonated with me or with my editor.

I've talked before about the image that prompted this novel initially--although, alas, that too has changed somewhat--and about the difficulties I've had with titles generally. But naming a book is a difficult thing--it has to be right! The new title--A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET--feels right. (I mean, I also liked Murder at Fleet Ditch, but it was deemed a bit too harsh for my Lucy books, which I can totally see now). Here is the working premise: Crossing Holborn Bridge, where it crosses the River Fleet, Lucy Campion—printer’s apprentice--encounters a distraught young woman, barely able to speak and clad only in a blood-spattered nightdress. To the local townspeople, the woman is mad, afflicted with the devil’s tongue, but Lucy, feeling concerned for the woman’s well-being, takes her to a physician. When the woman is shockingly identified as the daughter of a nobleman, Lucy is asked to temporarily give up her bookselling duties to discreetly serve as the woman’s companion while in the physician’s care. As the woman recovers over the month of April 1667, she begins—with Lucy’s help—to reconstruct the terrible event that occurred near the bridge, as well as the disturbing events that preceded it. When the woman is attacked while in her care, Lucy becomes unwillingly privy to a plot with far-reaching social implications. But, given that I don't like to disclose too much about my work-in-progress, this is all I will say! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed