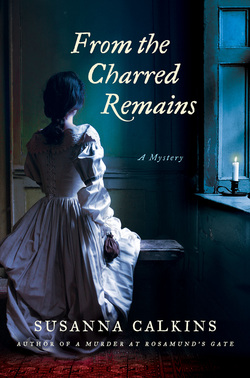

Anyone who knows me, knows I really love doing puzzles. Even when I was a kid, I was always doing puzzles--from word searches to crossword puzzles to substitution ciphers (probably because I felt like I was really decoding mysteries). But when I was in graduate school, I first encountered the fun of acrostics. In the high Middle Ages, scholars like Alcuin of York (Charlemagne's tutor) used to write short poems that contained clever messages--sometimes hidden--when read a certain way. In their simplest form, the first letter of each line would be carefully selected so that, when read down, the reader could discern a message. However, they could be more complex as well, which always fascinated me. I just knew that I had to work acrostics and other puzzles into my story, when I came across this acrostic published just after the Great Fire of London in 1666: London's Fatal Fal, an acrostic. Lo! Now confused Heaps only stand On what did bear the Glory of the Land. No stately places, no Edefices, Do now appear: No, here’s now none of these, Oh Cruel Fates! Can ye be so unkind? Not to leave, scarce a Mansion behind… Working out my own acrostic--and actually several hidden anagrams within the acrostic (shhh!!!)--was probably the most challenging and fun part of writing From the Charred Remains. But puzzles abound throughout the entire novel. There is even a secret hidden on the cover of the book, which you will understand after you read it!

1 Comment

Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 As I'm finishing up my third historical mystery--The Masque of a Murderer--I found that I still had a few more things to research. In particular, what would commoners living in 17th-century London have known of chocolate, and how might they have experienced it for the first time? References to "chocolate" in England can first be found in the 1640s. Of course, "chocolate" as a substance had been around for several thousand years as Smithonian.com explains, originating in Mesoamerica. However, it did not find its way to Europe until the early seventeenth century, as one of the strange products imported from the New World. The word "chocolate" comes from the Aztec word "xocoatl," (or is it the Nahuatl word chocolatl?) referring to a bitter drink derived from cacao beans, with medical and health properties (for more about the etymology of the word, check out Oxford Dictionaries blog for ten facts concerning the word Chocolate... ). By the 1650s, several discourses on the "physicks" and health properties of chocolate were in circulation in London. In 1640, "A Curious Treatise of the nature and quality of Chocolate" by Antonio Colmenero, a Spanish"Doctor in Physicke and Chirurgery, was translated into English. More significantly, Henry Stubb published the far more substantial treatise on "The Indian Nectar" in 1662. We know too, from a collection of 1667 statutes from King Charles II that there were restrictions on who could sell chocolate: "And be it further Enacted by Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said first day of September, no person or persons shall be permitted to sell or retail any Coffée, Chocolate, Sherbet or Tea, without License first obtained and had by Order of the General Sessions of the Peace in the several and respective Counties,etc etc." This makes me reasonably certain that chocolate would have been sold at coffee houses, for those would have been the establishments likely to acquire such a license. It is unlikely that chocolate would have been sold at taverns or alehouses, at least in early Restoration England, due to the great dispute between those who sold wine and beer, and those who sold coffee. Chocolate might have been procured for medicinal purposes as well, although it is unclear to me--at least at this preliminary stage--whether it would have been actively prescribed by a physician. However, if the "Virtues" are to be believed (of course, that's if they are to believed), chocolate cures infertility, "ill complexion," digestive illnesses, consumption and "coughs to the lungs," "sweetens the breath," "cleaneth the teeth," "provoketh urine" and "cureth the stone." Apparently, this miracle drug also cures "the running of the reins," (the last a euphemistic biblical reference to venereal disease). Who knew? I have to surmise a bit here, on how popular chocolate truly was in Restoration London. But I think it's reasonable to assume, especially once sugar became a more common household good, that it would have been become popular fairly quickly. (Although it's also likely that it remained in the realm of the elite and wealthy, for quite some time.) But what do you think? England and Wales. A collection of the statutes made in the reigns of King Charles the I. and King Charles the II. with the abridgment of such as stand repealed or expired. Continued after the method of Mr. Pulton. With notes of references, one to the other, as they now stand altered, enlarged or explained. To which also are added, the titles of all the statutes and private acts of Parliament passed by their said Majesties, untill this present year, MDCLXVII. With a table directing to the principal matters of the said statutes. By Tho: Manby of Lincolns-Inn, Esq. 1667 Wing (CD-ROM, 1996) / E898

Wing / 2532:08 |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed