Can Jung explain coincidence? _I was reading a mystery today, enjoying the story, when I was brought to a screeching halt. The author had introduced a rather significant coincidence into the story--two seemingly unrelated events--which of course became pivotal to the plot. I wasn't bothered by the coincidence, but rather by how easily the heroine assumed that these events--a distant relative's death from natural causes and the disappearance of a local person--just HAD to be connected. It felt a bit clumsy, a bit contrived. I know that history is full of crazy coincidences, but as a reader, I wasn't sure that it worked. I felt a little manipulated by the author. HOWEVER, my husband, a cognitive psychologist, had a different take. He said that the character's insistence that the events had to be linked exemplifies two things. First, that people naturally look for patterns, even when no patterns exist. Second, people feel the need to account for extraordinary events with extraordinary explanations, even when a common explanation would suffice (also called the "Spectacular Explanation Fallacy.") So, for example, have you ever been humming a tune, and when you next turn on the radio, that same tune is playing? Or have you ever dreamed about a friend, and the next day she calls you? Strange, right? But how do you explain it? A divine being at work? ESP? Fate? Alignment of the planets? Jung's collective unconscious? Producers manipulating your life? (okay, think Truman Show for the last one). So I'm curious about two things: Have you ever been thrown off by a coincidence that seemed too jarring to be credible, as either a reader or as a viewer? Have you ever experienced a coincidence that's stranger than fiction? So, ultimately, should a coincidence be plausible?

11 Comments

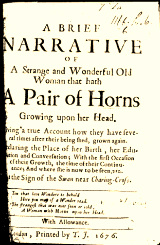

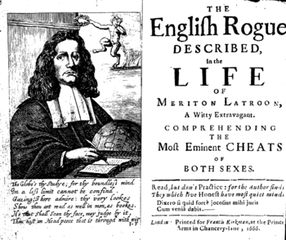

The woman who gave birth to a cat (really!!) has to be one of my favorite stories from the archives. Poor Agnes Bowker--a young woman who did not want to admit what had happened to her child--claimed in 1569 that a monster (actually an ordinary feline) had emerged from her womb. None of the six women present at the birth could say for sure what had happened. Although a silly tale, the case was investigated thoroughly, as the Tudor government had a vested interest in maintaining order. And widespread gossiping about the supernatural was decidedly disorderly.  As I've mentioned before,such cases ("true accounts," "strange newes"; "wonderful happenings") have done much to inspire my own writing. But what's the truth of them? We can't completely know. We do know such stories shed light on how early modern villagers and townspeople understood the world around them, often revealing thinly disguised wrongs, moral tales, and political allegories. Some simply targeted people different from them, such as the "wonderful old woman" who had "a pair of horns growing upon her head."  _Others disguised everyday criminal events. The "Strange and Wonderful News from Kensington" (1674), for example tells of a maid "carryed away by an evil spirit" convinced to steal heartily from her master. (The Devil made her do it, anyone?) Whether anyone actually believed this servant is another question altogether. But of course, booksellers were looking to make a penny. And that tradition has kept many a tabloid in business. Some classics are apparently worth keeping. Just as the seventeenth-century bookseller once warned that a "True and Wonderful serpent (or dragon)" had been lately discovered in Horsam,the National Enquirer duly informs us that the Loch Ness Monster has been found by GoogleEarth!  Compare the 17th century discovery of a murderous serpent with GoogleEarth locating the Loch Ness monster! _ _Are we really so different today? We may feel more rational, less credulous--but are we really more "truthful?" Have we just found new, re-imagined, more scientific ways to explain the inexplicable? What do you think?

Did Scarlett J. do this character justice? _After I viewed the trailer for Hunger Games, I admit I breathed a great sigh of relief. The young woman playing Katniss (Jennifer Lawrence) seemed spot on, as did the young man in the role of Gale (Liam Hemsworth). I have to say, too, that Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) looked better than what I imagined. The movie looked exciting, and more importantly, seemed true to this tense and unpredictable book. Why was I worried, you might ask. Like every reader, I had imagined these vivid characters--and the whole world--in a certain way, bringing my own sensibilities and experience into the book. Sometimes, it's really hard when an actor seems all wrong for the character. (Case in point--I enjoyed Matthew Macfadyen in MI-5, but I think he really misunderstood Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice--and not just because the wonderful Colin Firth had already dominated the role). I always wonder what it's like for authors to see how others view their characters. Perhaps sometimes the characters dance off the pages, just as they'd imagined, while at other times emerge as virtual strangers. For my part, I garner physical descriptions for my characters by seeking out visual cues. Sometimes I rely on period art, as I think Tracy Chevalier may have done with Vermeer's The Girl with a Pearl Earring, to get a feel for how someone in early modern England might dress or wear their hair, and to ponder their worldview. More often than not, I find photos of real actors to help me remember what each of my characters is "supposed to" look like, at least to me. Hmmm...I could share those photos and images, if I wanted to. I'm pretty sure, however, it's cheating when you tell readers how they are supposed to think. So as a writer, I'll stay hands-off about my own characters. I accept that characters are negotiated through the lenses that readers bring to the text. As a reader, I admit I often don't want that negotiation to happen. I want to see on the big screen exactly what I see in my mind's eye. Otherwise, I'm confused, even disappointed. Johnny Depp as Willy Wonka? George Clooney as Batman? Jim Carrey as the Grinch? I'm not so sure. But sometimes characters evolve from author to reader to viewer, when in deft hands. Consider Matt Damon as Jason Bourne. Robert Downey Jr. as Sherlock. Emily Deschanel as Temperance Brennan. And yes, Scarlett Johansson as Griet, the Girl with a Pearl Earring. None of these characters were really rendered as the author wrote them, and yet I was satisfied, even intrigued, in their re-imagining. The problem at that point, of course, is when everyone says: 'I think the characters were better in the movie than in the book." ARGHHHH! What do you think? Have you ever been surprised--pleasantly or unpleasantly--when a character is portrayed very differently than what you had imagined?  The original rock-a-bye baby Why is my five-year old speaking caustically about the French Revolution? How is he able to make critical remarks about England's Glorious Revolution? I mean, he's brilliant and all (I joke!) but really! How does he know about such things? Well, the short answer is, he doesn't. He's just chanting words many of us learned when we were kids, about Jack and Jill and babies rocking in tree tops. Mother Goose Rhymes? Nope, try re-appropriated tavern songs and ballads. (Similar to "Ring-Around-the-Rosy's" dismal connection to the Bubonic Plague and the Danse Macabre. I'd have talked about that, but that's old hat! Old hat?) Next time you're humming that old tavern tale, er, nursery rhyme "Rock-a-bye baby," imagine the real context. It's 1688. Protestant England is being ruled by James II. Despite the King's overt Catholic tendencies, Parliament and the people are generally fine with their ruler. After all, in due time, his daughter Mary--married to William of Orange, a good Protestant--would inherit the throne. But when rumors start to spread that the Queen had secretly borne a male heir--or stolen a child, smuggled into England in a warming pan, if you can believe THAT!-- a child who would surely return the country to Catholicism, the people rebelled. They overthrew James II, cast off the baby, and gave the throne to Mary to rule jointly with her husband. So how is all this revealed in the most everyday of songs? Check it out! "Rock-a-bye, baby" (the warming pan baby, James III) "On the tree tops" (I think the tree represents the English monarchy) "When the wind blows" (the Protestant wind blowing in from the Netherlands, with William and Mary) "The cradle will rock." (The cradle is the monarchy being rocked). "When the bough breaks," (Again, the tree) "The cradle will fall, and down will fall baby, cradle and all." (The End of the English monarchy!! Huzzah!) A whole different perspective, right? But the other story--Jack and Jill--tells a much more bloody tale. Well, okay, some say "Jack and Jill" is referring to the economic downturn in early seventeenth century England. In this version, Charles I commanded that the volume of a 'Jack" (1/2 pint) be lowered because it was too costly ("broke the crown"), and the "Jill" (or gill, 1/4 pint) came tumbling after. But that's less fun. I like the version that ascribes the nursery rhyme's origins to the French Revolution. Very simply: "Jack and Jill" (the luckless King Louis XVI and his wife, the much maligned Marie Antoinette) "Went up the hill" (They mounted the scaffold in 1793. You see where I'm going here?) "To fetch a pail of water." (Okay, not sure about this line! any thoughts?) "Jack came down, and broke his crown," (Executed by the slicing dicing guillotine) "And Jill came tumbling after." (Marie Antoinette executed a few months later. That guillotine was awfully efficient. But again, the end of a monarchy.) What do you think? Fun stuff, right?  _ When I was first writing Monster at the Gate, I toyed with the idea of writing the whole book in authentic seventeenth century prose. That idea lasted about two seconds. Partly because that trick's been done, you know, by actual writers from that time period, like Defoe. And partly because I thought readers might throw rotten tomatoes at me for writing in such a cumbersome manner (heck, I might throw them at myself). But mainly, it was because many seventeenth-century words and phrases don't translate readily today, and unless my editor lets me write a companion volume with glossary and explanatory footnotes, I don't think it would work (assuming I had the patience for such an endeavor, which I don't). For example, criminals and thieves created their own language, "cant," which was deliberately designed to hide their shadowy doings. Amazingly though, a few curious contemporaries, such as Richard Head, decoded this elusive criminal language in cant dictionaries (similar to modern slang dictionaries), basically as a public service to let their readers in on what the criminals were doing. So, for example, a thief might Bite the Peter or Roger (which our good Richard tells us means "steal the port-mantle or cloak-bag"), proceed to Tip the Cole to Adam Tyler ("give what money you pocket-pickt to the next party") , who might take it then to a stauling ken(a "house that wyll receaue stolen ware.") (I guess we'd say 'fence?'). Some phrases are even harder to translate. So, say a broadside depicts what happens to a criminal who is caught. It might read: “As the Prancer drew the Quire Cove at the Cropping of the Rotan through the Rum pads of the Rume vile, and was flog’d by the Nubbing-Cove.” Huh? Any guesses? No? Really? Well, according to J. Coleman's History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries (Oxford, 2004), that statement translates to: “That is, The Rogue was drag’d at a Carts-arse, through the chief streets of London and was soundly whipt by the Hangman.” You probably knew that. Awesome stuff! But I'm curious. Have you read any terrific (modern) books that were written completely in dialect? Did you find them hard-going? fun? or something in between? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed