|

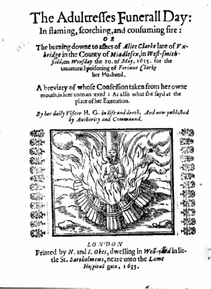

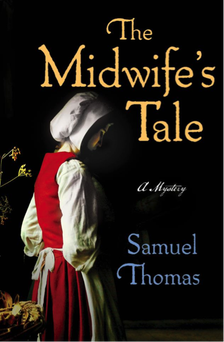

I am excited that Sam Thomas, author of The Midwife Mysteries, was able to join me on my blog today! To celebrate the fact that The Midwife's Tale is now available as an E-Book for just $2.99, Sam shares the story behind his cover! (Head over to Amazon or Barnes & Noble to pick up your copy!) One question that a lot of readers have asked is how The Midwife’s Tale wound up with its cover, and whether I had any say in its creation. It’s a pretty great question with an interesting answer. When I envisioned the cover of The Midwife’s Tale, I wanted it to look like a seventeenth-century book, largely in keeping with my original title, Bloody News from York. The image I had in mind was something like this book from 1635: I thought that this cover would both capture my setting and the central tension of the book, whether a woman would be burned at the stake. Unfortunately, kept this idea to myself for a bit too long, and before I said anything to my editor, he sent this cover: I was floored. I loved the darkness, the color scheme, the way the light played across the figure’s back… nearly everything about it.

The one concern my agent had was that it seemed a bit too still. I had written a murder story, after all, and he thought it could use a bit more danger. We suggested putting a knife in her hand, and perhaps replacing the stalks of grain on the table with a mortar and pestle. This is where Minotaur came through for me the first time. By all rights, they could have said, “Nope, this is it.” But they didn’t. They came back with a modified cover:

2 Comments

I am pleased to re-post a blog entry written by Christy Robinson about recent 17th century novels. The post originally appeared on Christy's blog. Christy's novels focus on William and Mary Dyer, two famous 17th century Quakers who also happened to be her ancestors. There’s a vast crowd of enthusiasts reading and discussing everything medieval and renaissance. But time didn’t stop with Elizabeth Tudor’s death in 1603. Are you looking for the rest of the story?

King James I, his son King Charles I, and grandsons Charles II and James II kept the drama level high and dangerous in the seventeenth century, with their marriages and lovers, births and deaths, political intrigues, religious conflicts, witch hunts, and wars. [Along with, of course, Oliver Cromwell and William and Mary -SC] Their aristocrats and politicians, tradesmen, midwives, ministers, writers, musicians, scientists, and artists changed the world. Have you noticed that it’s the gift-giving season? Why not knock out your whole gift list right now with these suggestions? The gift of a book is one that's remembered for years. Some people find it convenient to buy books for all their siblings, or as appreciation gifts for their children’s teachers. You might give paperback books to some in the family, or use the Kindle-gift option. Some books are stand-alone, some are part of a series. This is a list of authors who have the 17th century covered, from Shakespeare and midwife investigators to barber surgeons, Charles II’s mistresses, men and women who founded American democracy, servants and highway robbers, people who gave their lives for their principles or just because they were falsely accused as witches. In these books you’ll find sumptuous gowns and high society, educated women, poverty, prostitutes, and massacres, childbirth and plague, castles and manors, cathedrals and meetinghouses—even a vampire. Our ninth or tenth great-grandparents [at least Christy's!-SC] knew these people—or were these people. (Well, probably not the vampire—but everyone else!) Discover what their lives were like...Many of the book characters from the 17th century are based on facts, events, and real people. The authors, in addition to their literary skills, have spent months and years in research to get the 17th century world “just right,” so you’ll get your history veggies in a delicious brownie. Ride the wave of the time-space continuum into the 17th century with these award-winning and highly-rated authors. The images you see are a small sample of what's available from this talented group! Click the highlighted author’s name to open a new tab. Anna Belfrage — Time-slip (then and now) love and war. Jo Ann Butler — From England to New England: survival, love, and a dynasty. Susanna Calkins — Murder mysteries set in 1660s London. Francine Howarth — Heroines, swashbuckling romance. Judith James — Rakes and rogues of the Restoration. Marci Jefferson — Royal Stuarts in Restoration England. Elizabeth Kales — French Huguenot survival of Inquisition. Juliet Haines Mofford — True crime of New England, pirates. Mary Novik — Rev. John Donne and daughter. Donald Michael Platt — Spanish Inquisition cloak and dagger. Katherine Pym — London in the 1660s. Diane Rapaport — Colonial New England true crime. Peni Jo Renner — Salem witch trials. Christy K Robinson — British founders of American democracy and rights. Anita Seymour -- Royalists and rebels in English Civil War. Mary Sharratt — Witches (healers) of Pendle Hill, 1612. Alison Stuart — Time-slip war romance, ghosts. Deborah Swift — Servant girls running for lives, highwaywoman. Ann Swinfen — Farmers fighting to keep land, chronicles of Portuguese physician. Sam Thomas — Midwife solves murders in city of York. Suzy Witten — Salem witch trials. Andrea Zuvich — Vampire in Stuart reign, Duke of Monmouth and mistress.  Among the many things I never expected when I began to publish my historical mysteries is the steady stream of questions I get from readers. I really enjoy getting these questions, but sometimes I'm a little perplexed. The "easy" questions focus on interesting historical details, like how people kept time in the 17th century or what the revolving signet ring described in From the Charred Remains actually looked like. Sometimes they focus on larger questions, such as the gendered nature of the printing industry, the so-called "miracle" of the Great Fire, and the like. Sometimes, I just answer these history-related questions in a quick email, but I will probably start answering them in more detail on this blog. However, what's interesting to me is the number of questions that I'm starting to get about the decision-making processes that accompany the writing of a novel, especially historical fiction. "How do I decide on a time period/setting for my novel?" "How do I begin my research?" "How much research do I need to do?" "How much historical detail is enough?" "Do I need footnotes?" I hate to say it, but all of these questions can be answered in a single phrase. It depends. I know, I know. That's not very helpful. Since I've written at length in Writers Digest about seven tips for writing historical fiction,"Balancing accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction," I won't go into detail about those writing strategies here. And really, I don't have any particular insights about how to select an interesting time period. Choose a time period that fascinates you, intrigues you, keeps you enthralled. Keep in mind: this time period had better hold your attention, since writing a novel takes a very long time indeed! If you become bored with the time period, I have no doubt it will show in your writing, and your reader will become bored too. Truly, to answer such questions: "Have I done enough research?" "Have I offered enough historical detail?" "Do I need footnotes?" it really does depend on who your intended audience is, the kind of book you are writing, and the conventions of the genre. To answer these questions, there's a bigger question that you really need to ask yourself first: Am I actually writing historical fiction? This seems like a simple question, but I've been quite surprised when readers and writers ask me about the difference between history and historical fiction. It's clear to me now that there is a spectrum of categories, associated with the writing of history. None is "better" than another--each has a different purpose. I thought I would lay out how I conceptualize the difference in these categories: (1) Scholarly historical writing: This type of non-fiction writing is usually conducted by scholars and academics, produced in institutions of higher learning, museums and libraries, with highly specialized audiences and very small print runs with academic presses. Historical narratives and interpretations are framed by theory, historiography, with a strict adherence to evidence found in primary and secondary sources. Footnotes are crucial for credibility. Usually peer reviewed by other scholars/specialists before proceeding to publication. (2)Popular historical writing: This non-fiction writing may be very similar in scholarship to academic writing, but it may be more sensational in nature; it may be mass produced by commercial presses and readily found in bookstores; less emphasis may be placed on historiography and theory, but these features may still be present. Standards of evidence may be less strict. May not be peer reviewed, or only reviewed by editors. Generally, the writing seems more accessible and is intended for a lay audience. Footnotes are present, but are used more to explain ideas than to provide citations for every piece of evidence (again, this varies by publisher). (3) Fictionalized History: This is a tricky category to explain, because I think it is usually lumped together with historical fiction. I think this occurs when a writer takes a well-known historical narrative and adds to this narrative with made-up conversations and interactions between real historical figures. There is a great deal more supposition and creative license in constructing this type of narrative. Evidence may be selectively used to frame the overall story. Footnotes may be expected by readers. I think it is safe to say that this category can be called "Based on a True Story." (4) Historical fiction: While this varies, I would say that in this category, the historical narrative usually forms a backdrop to the story, with characters interacting with authentic details. Background theory and research will inform the best writing in this category, but will be implicit, not explicit. Historical fiction is not usually produced by academic presses, and undergoes editorial, not peer, review prior to publication. Much of the main plot may be fictionalized, even if there are real characters and true historic events being described. So in my case, the 17th century plague and the Great Fire of London form the backdrop of my stories, and my completely fictional characters sell murder ballads, spend time in Newgate prison, and scrub chamberpots. I do not have footnotes (ack! ack! not in a novel! Convention right now, at least in traditional publishing, is to eschew footnotes), but I do have a lengthy historical note in each book to explain historical points more or to indicate where I stretched the facts slightly to enhance the storytelling. I avoid information dumps, and try to get my characters to engage with the historical details. I'm telling a story, not writing a textbook. In any one of the above-mentioned categories, however, writers may be seeking to shed light on a little known historical event or figure, to expose larger truths, to offer new explanations and interpretations about a historical event or idea, or simply to provoke curiosity about a bygone era. One category is not BETTER than another; there are different purposes for each (and there are examples of good and poor writing in every category.) Ultimately, the level of historical detail and the length of the book will depend upon your intended audience (children, adults, scholars, history enthusiasts etc), the opinion of your editor and publisher, the conventions of your genre, and most importantly, the story you are trying to tell. But what do you think? Do these categories make sense? I'm so excited....Bouchercon is just a few days away. MURDER. AT. THE. BEACH. What could be more fun than that?! This will be my fourth time at this fabulous meeting of mystery readers, authors, publishers etc, and I can't wait!

All my stuff happens on the Thursday, which frees me up for hanging out at the bar, er, "networking" for the rest of the conference. First, I will be on an awesome panel called "Chills, Thrills, and Mysteries in the 17th to 19th centuries" (Thursday, November 13, 2014 2:30-3:30 pm Regency A), to be moderated by Laura Brennan, with some wonderful authors Emily Brightwell, Charles Finch, Eleanor Kuhns and Suzanne (SK) Rizzolo. Seriously, how much am I looking forward to chatting with these writers? A lot! Then, a few hours later, I will be at the Murder at The Beach "Hollywood Premiere" Opening Ceremonies 6:30 pm. I'm honored to say that my first novel, A MURDER AT ROSAMUND'S GATE was nominated for a Sue Feder Historical Macavity Award (so exciting!). The winners will be announced during this session. And just in case you are wondering, the answer is, "No I do not have anything ready to say on the off chance the world flips upside down and my name is called." There's not much need to prepare when you're up for an award alongside fabulous authors like:

The cliche is true: It truly is an honor to be nominated. But thankfully none of the other nominees start with a "Su-" sound, so I won't be halfway to the stage before I realize it wasn't my name called. ("Ahem, I was just taking a little walk. You know, to congratulate the winner. Right during the ceremony. That's okay isn't it? No? Should I just sit down then? Okay, I'll do that.") However, I'll write about the experience afterwards and let you know how it goes! Wish me luck! (and them too, of course! ;-) ) |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed