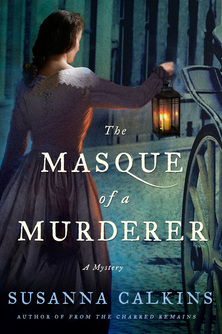

I'm so happy and honored to say that my third historical novel, The Masque of a Murderer, officially launches today, April 14! And while I may not be quite as giddy when my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate (2013) launched two years ago--because nothing can ever compare to the release of a first novel--I'm still as loopy as I was last year, when From the Charred Remains (2014) entered the world. Recently, in preparation for the launch, I've been answering a lot of fun and interesting questions about The Masque of a Murderer (the historical background, the story and characters, and my writing process etc). So, I thought I'd do a quick round-up here! I welcome you to:

Thanks so much for sharing this journey with me!!! And I appreciate all the bloggers and reviewers who hosted me, including those through Amy Bruno's Historical Fiction Virtual Blog Tours! And I'm always so grateful to the wonderful people at Minotaur, especially Kelley Ragland and Elizabeth Lacks, and my agent David Hale Smith, and of course my wonderful alpha reader, Matt Kelley!! (and now, I turn my attention back to A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, due out April 2016!!!!)

1 Comment

In my third historical mystery, The Masque of a Murderer, Lucy Campion, printer's apprentice, has been asked to record the last words of a dying Quaker. He had been run over by a cart and horse the day before, and was slowly dying from his extensive injuries. A number of people have gathered by his bedside, listening to his final rambling words, testifying to his journey from sinner to one who has found the "Inner Light." And before the man finally succumbs, he regains a moment of lucidity and manages to tell Lucy that he had, in fact, been pushed in front of the horse and his death was no accident. Moreover, he believed that his murderer had to be one of his closer acquaintances, perhaps even a fellow Quaker. The premise came from a tradition that was common in early modern England of recording the "last dying speeches" of different types of individuals. Such speeches were common for criminals about to be executed, for example, and which would be distributed at the gallows for eager spectators. [In From the Charred Remains, I have Lucy selling some of these at the public hanging of a criminal]. Often written by clergymen, such chapbooks or pamphlets were usually both pious and didadic in tone. As historian J.A. Sharpe has put forth: “The gallows literature illustrates the way in which the civil and religious authorities designed the execution spectacle to articulate a particular set of values, inculcate a certain behavioral model and bolster a social order perceived as threatened. Only a small number of people might witness an execution, but the pamphlet account was designed to reach a wider audience.”*  Wing W2039 Wing W2039 Indeed, there was a similar quality to other types of sinner's journeys that were published as chapbooks or pamphlets. Quakers, who produced hundreds of tracts in the 17th century, frequently recorded the last words of Friends whom they wished to hold up as a means to extol a certain value or set of virtues for others. For example, when I was writing my dissertation on 17th century Quaker women, I came across a poignant tract--The Work of God in a Dying Maid (1677)**--written by one of the more prominent Quaker leaders, Joan Whitrowe, detailing the death of her daughter, fifteen-year old Susannah. The 48-page tract tells the story, not just of Susannah's death, but of the young girl's early struggles with temptation. The testimonies, written by Joan and other local leaders, demonstrates how Quaker children and youth were supposed to behave, and why they should listen to the advice of their parents and other elders. Indeed, Joan dedicates the work as a warning to those wayward souls, "who are in the same condition [Susannah] was in before her sickness." But the back story that emerges throughout the pious testimonies is quite compelling. As Susannah lay dying in her Middlesex home in 1677, neighbors whispered that the cause of her "distemper" was a recently thwarted romance. Questioned by her parents, the young Quaker admitted that a certain man was "very urgent with [her] upon the account of Marriage" and since her father had been a "little harsh" to her she thought she would set herself "at liberty." But upon reconsideration she allegedly told her suitor, "I would do nothing without my Father and Mother's advice." She assured her mother, "before I fell sick this last time, I did desire never to see him more." [Here are some of the lessons about virtue and obeying one's parents--and the consequences of not doing so.] Feverish, restless, and in pain, the young Quaker reportedly clamored for God's swift judgment, mercy, and an end to her suffering. For six days her mother and father and various friends maintained an anxious vigil at her bedside, praying and recording Susannah's final excited visions and earnest penitent speeches to God. She chastised herself for her vanity, "How often have I adorned myself as fine in their [her female acquaintances] fashions as I could make me?" She berated herself for bringing shame to her family and lamented speaking out against her mother’s sect: "Oh! How have I been against a woman's speaking in a [Quaker] meeting?" What we can not know of course, is how much of this Susannah actually said, and how much was expanded upon in the written narrative to make the larger point about godliness. But it gives a sense of the way that people's final words were recorded, and it offers a fascinating backdrop for a murder mystery... *J. A. Sharpe, "Last Dying Speeches": Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England. Past & Present No. 107 (May, 1985), pp. 144-167. quote on p.148.

Joan Whitrowe, The Work of God in a Dying Maid: Being a Short Account of the Dealings of the Lord with one Susannah Whitrowe (n.p., 1677), 16.

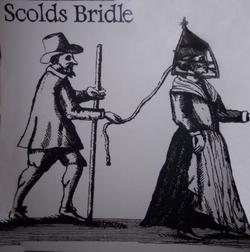

Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Every morning, when I check my email, I'm reminded of a funny (funny-weird, not funny-humorous) thing about book titles. Because I have a daily Google alert on my titles, I get a little summary about how they have used been used on the internet. For my first novel A Murder at Rosamund's Gate and for my third novel, The Masque of a Murderer, I get alerts that actually pertain to my book. But for my second book, From the Charred Remains, I am treated to all sorts of terrible and strange news stories--usually house fires--of things or people being found after a fire (this gem to the right is one of the better things that's come this way). Literally, this illustrates the dark side of book titles. There are terrible things that happen in the world--beyond what happened on the mythical Tatooine--and every day those come to my inbox because of how I titled my book. I shouldn't be surprised--after all, the premise of my book is that a body has been found in a barrel outside the Cheshire Cheese after the Great Fire has devastated much of London. So as I sort though new titles for my fourth book--the soon to be renamed Stranger on the Bridge--I find myself avoiding titles that reporters might use to describe particularly grisly stuff. It's ironic really. The title of my first book didn't make it through marketing, but it was originally called Monster at the Gate. I thought the concept of monster fit well with my time period, but that title was deemed too harsh and supernatural. I can only imagine the kinds of Google hits I would have gotten, had I kept that title. The original title of my third book, Whispers of a Dying Man, didn't make it past my own internal scrutiny. Bleagh. Glad I changed that one. The Masque of a Murderer is a much better title. But From the Charred Remains sailed through easily. I still like the title, but I'm still a bit wary when I see what Google has sent me. Now, I'm still pondering the title of my fourth book. Stranger on the Bridge just isn't resonating for me. So at New Year's, after describing the premise, I asked a bunch of my friends to all put single words (nouns and adjectives) into a hat. Then we all picked three or four slips of paper and formed titles. The best of this admittedly drunken endeavor was Across the Misty Divide. Probably won't go over either (sorry Steve!). Maybe the parlor game method of naming books is not the best method. So hopefully something connects soon!!! I'll keep you posted!  This never gets old...so exciting to get the copy edits for my third Lucy Campion mystery--The Masque of a Murderer! I am hoping to reveal the cover soon. I've seen an early version and I love it! Can't wait! (To be released on April 14, 2015, but available now for pre-order at Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and a bookseller near you!)  The scolding wife Date: 1670-1696 Tract Supplement / A2:4[78] The scolding wife Date: 1670-1696 Tract Supplement / A2:4[78] I won't say HOW exactly, but a scold's bridle features prominently in my third novel, Masque of a Murderer. (Well, okay, maybe one is found on the corpse of a young woman. Or not.) But the bridle does play an important role, and I thought I would give a little more background. Since at least the Middle Ages, women had been expected to heed Paul's admonition to be "chaste, silent and obedient," an expectation that became even more pronounced for women in early modern Europe. Women were branded "scolds" if they harangued their husbands or neighbors, or as we may say today, spoke their minds. "The Scolding Wife," shown here, is one of many tales of a merry young man who made the mistake of marrying a rich widow who very quickly made his life miserable. Indeed, the couple couldn't even sit down to eat without her scolding him: "They was not all at supper set, or at the board sat down, Such accounts explain how the men's good will and cheer are sapped by the woman's speech. It should be noted, however, that the tale is to be 'set to a pleasant tune.' The ballad is meant to be lighthearted--an everyday tale of a man who cannot control his wife. As such, it is as much a comment about his nature as it is about hers. Nevertheless, there is a gendered warning here about the respective roles that men and women should play in a marriage. My favorite of these little discourses is one by Anonymous (1684): "The tongue combatants, or A sharp dispute between a comical courageous country grasier, and a London bull-feather'd butchers twitling, twatling, turbulent, thundering, tempestuous, terrifying, taunting, troublesome, talkative tongu'd wife." Hmmmm.....  Sometimes, however, the warning against women's scolding was more explicit--and more terrifying. Devices known as scold's bridles, or scold's masks, first emerged in the Middle Ages, and continued to be used (in England at least) throughout the early modern era. The scold's mask was a painful contraption of iron and leather that fit over a woman's face that effectively prohibited her from speaking. Sometimes, the woman might be paraded about, as a humiliating reminder to keep her opinions to herself, and as a lesson to other women who might be inclined to do the same. So how does this play out in my novel? Find out in April 2015, when Masque of a Murderer is released!  Well the last ten days have been fun, fun, fun, and crazy, and I don't know what else. Hence, the reason I am writing a post at four in the morning. (This effect could also be called: "Why Susie should not drink a medium latte at 9 PM"). A week ago, I had the fun of seeing my second novel, From the Charred Remains, out in the world. (From that day 'til now, I also had a class full of essays to grade, several big reports to write for work, a full-day faculty retreat to run, classes to teach, and a plenary on critical thinking to facilitate for 150 law professors, so to say my week was a bit nuts is a mild understatement.) (*But work is work, and writing is writing, and ne'er the twain shall meet!) In between, I frantically got one post out for Criminal Element, where I discuss "Crime-Solvers: Forensics of the Past." And, well, I am trying to finish book 3--The Masque of a Murderer--**which I promise, my dear editor Kelley, is nearly done. ***Gritting my teeth while smiling is about where I'm at these days. But a quick recap of the last ten days in photos: In a few hours, I will be taking the train down to Bethesda, for the Malice Domestic Conference. It's always so much fun to connect with other mystery lovers. I have a panel on Sunday, May 4, 2014 11:45-12:35, called "One Is Not Amused by Murder: Historical English Mysteries." I'm delighted to be on this panel with fellow historical mystery authors: Kate Parker, Sam Thomas, and Christine Trent. The moderator will be Donna Andrews.  And on Thursday, May 8 at 7 pm, I'll do a talk at ArrivaDolce, the coffee shop where I do a lot of my writing. Someone will win this coffee and book themed basket! Hope to see you there! *Disclaimer to work colleagues who might read my blog.

**Disclaimer to my editor and agent, who might read my blog. ***Disclaimer to my dentist, who might read my blog. Okay, now I'm getting the 4 a.m. loopies.  Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 As I'm finishing up my third historical mystery--The Masque of a Murderer--I found that I still had a few more things to research. In particular, what would commoners living in 17th-century London have known of chocolate, and how might they have experienced it for the first time? References to "chocolate" in England can first be found in the 1640s. Of course, "chocolate" as a substance had been around for several thousand years as Smithonian.com explains, originating in Mesoamerica. However, it did not find its way to Europe until the early seventeenth century, as one of the strange products imported from the New World. The word "chocolate" comes from the Aztec word "xocoatl," (or is it the Nahuatl word chocolatl?) referring to a bitter drink derived from cacao beans, with medical and health properties (for more about the etymology of the word, check out Oxford Dictionaries blog for ten facts concerning the word Chocolate... ). By the 1650s, several discourses on the "physicks" and health properties of chocolate were in circulation in London. In 1640, "A Curious Treatise of the nature and quality of Chocolate" by Antonio Colmenero, a Spanish"Doctor in Physicke and Chirurgery, was translated into English. More significantly, Henry Stubb published the far more substantial treatise on "The Indian Nectar" in 1662. We know too, from a collection of 1667 statutes from King Charles II that there were restrictions on who could sell chocolate: "And be it further Enacted by Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said first day of September, no person or persons shall be permitted to sell or retail any Coffée, Chocolate, Sherbet or Tea, without License first obtained and had by Order of the General Sessions of the Peace in the several and respective Counties,etc etc." This makes me reasonably certain that chocolate would have been sold at coffee houses, for those would have been the establishments likely to acquire such a license. It is unlikely that chocolate would have been sold at taverns or alehouses, at least in early Restoration England, due to the great dispute between those who sold wine and beer, and those who sold coffee. Chocolate might have been procured for medicinal purposes as well, although it is unclear to me--at least at this preliminary stage--whether it would have been actively prescribed by a physician. However, if the "Virtues" are to be believed (of course, that's if they are to believed), chocolate cures infertility, "ill complexion," digestive illnesses, consumption and "coughs to the lungs," "sweetens the breath," "cleaneth the teeth," "provoketh urine" and "cureth the stone." Apparently, this miracle drug also cures "the running of the reins," (the last a euphemistic biblical reference to venereal disease). Who knew? I have to surmise a bit here, on how popular chocolate truly was in Restoration London. But I think it's reasonable to assume, especially once sugar became a more common household good, that it would have been become popular fairly quickly. (Although it's also likely that it remained in the realm of the elite and wealthy, for quite some time.) But what do you think? England and Wales. A collection of the statutes made in the reigns of King Charles the I. and King Charles the II. with the abridgment of such as stand repealed or expired. Continued after the method of Mr. Pulton. With notes of references, one to the other, as they now stand altered, enlarged or explained. To which also are added, the titles of all the statutes and private acts of Parliament passed by their said Majesties, untill this present year, MDCLXVII. With a table directing to the principal matters of the said statutes. By Tho: Manby of Lincolns-Inn, Esq. 1667 Wing (CD-ROM, 1996) / E898

Wing / 2532:08 |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed