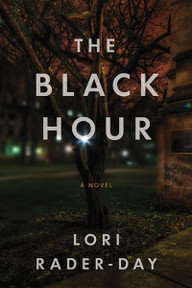

For many of us who work on college campuses, the specter of violence often looms. For instructors, there is an additional vulnerability, a sense of being studied and examined as intently as if they were the subjects of the course. In my day job, instructors frequently speak of feeling naked and exposed when they teach. Indeed, the public scrutiny can be tough for instructors. Even those who can bear it may still acknowledge a somewhat alarming truth: Students may know all kinds of things about us--often well before we know a single thing about them. So looking out at that sea of student faces, instructors may find themselves asking--who are these students, really? What are they thinking? What are they hiding? These are the kinds of questions that Lori Rader-Day explores in her stunning debut novel, The Black Hour (Seventh Street Books). In this compelling work of fiction, a sociology professor seeks to understand why a student she didn't even know tried to kill her. I invited Lori to chat about her novel on my blog. [Full disclosure: Lori and I work at the same university, although we actually met at Printer's Row in Chicago last year.]  The Talented Lori Rader-Day The Talented Lori Rader-Day Could you tell us about what inspired The Black Hour? I know that you work at a university—what role did that play in your inspiration? You don’t have to work at a university to worry about the violence happening on campuses across the nation, but because I do work at a university, it’s something I think about. But The Black Hour is more about the aftermath than the violence itself. The idea was: what would a first day back on campus be like for someone who survived an act of violence? Since the perpetrator was no mystery, the question had to be why. When I started writing, I didn’t know why, either. I had to keep writing until I knew why. The Black Hour is told through the alternating perspective of two individuals—the sociology professor who was the victim of the shooter, and a graduate student serving as her Teaching Assistant (TA). What contributed to your decision to tell the story using two voices? What were the challenges and the benefits of this technique? Originally I started the book from Amelia’s perspective. In the first few chapters, she met a new graduate student who was interested in her work studying violence. About 50 pages into writing the book, I realized I had a problem. Amelia was newly injured. How was she going to go scampering all over campus looking into her own attack? It turned out that the student, Nathaniel, had more to say. And then took over half the book. The challenge was in keeping the two first-person narrators separate so that a reader would know who was talking at all times, but the opportunities were greater. I had a lot of fun playing them against each other, and forcing them to share the story gave the novel its structure and pace.

2 Comments

what bad event might have happened here? what bad event might have happened here? Since my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate, was published in 2013, I have gotten many questions about my writing process. “Are you a plotter or a pantser?” is the question I most often get. Back then, I didn’t even know what the question meant. Now I know the questioner wants to know whether I outline my books in elaborate detail before I start writing (plotting), or do I go by the seat of my pants (pantsing), figuring out the plot and details as I go. I want to say that I’m usually captivated by an opening image—and that’s what my story revolves around. For my first novel, I have a young woman walking innocently up to a man she knows, who then surprises her by sticking a knife in her gut. Who was this woman? Why did she trust this man? And of course, why did he kill her? (Ironically, the image that inspired A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate never even made it into the final version. I had written it as a prologue, but I worried about starting the story twice. You can check it out here, if you are interested.). However, I've now learned that some things truly need to be figured out before I start writing the book. As I start my fourth Lucy Campion novel, I thought I'd try to share something of my process of thinking through the plot. I have my opening image, and--for now--a one paragraph description of the plot: When the niece of one of Master Hargrave’s high-ranking friends is found on London Bridge, huddled near a pool of blood, traumatized and unable to speak, Lucy Campion, printer’s apprentice, is enlisted to serve temporarily as the young woman’s companion. As she recovers over the month of April 1667, the woman begins—with Lucy’s help—to reconstruct a terrible event that occurred on the bridge. When the woman is attacked while in her care, Lucy becomes unwillingly privy to a plot with far-reaching political implications. So I have my opening image, but now I have to start thinking through all the big questions. Initially, I seem to do this as a reader. Who is this woman? What happened to her? What was this terrible event? Was it something that she witnessed, or is she physically injured. Whose blood is it? Why is she on London Bridge alone?

Then I will start the hard part--thinking through these questions as a writer. I've definitely learned that I need to figure out who the antagonist is from the outset. My natural tendency is to reveal the story to myself (pantsing), probably because I'm naturally more interested in how terrible events affect a community, not why people do terrible things. However, that approach usually means I don't know whodunnit, and that's a challenge for a mystery writer! I usually have to do a lot of backtracking and rethinking motivations and actions, when I have not worked out who the killer is upfront. So then, my next set of questions will be plot-related. What is this terrible event that occurred? Why did it happen? Who caused it to happen? How did this young noblewoman get involved in such a thing? And--sadly enough--I need to figure out if the London Bridge will work as a backdrop. I know it got burnt in the Great Fire, but I'm not sure yet how feasible it is that she ends up there. Then, because Lucy needs to be brought in, I need to figure out what makes this so urgent. Will this woman be attacked under Lucy's care? Probably. Why? What does she know? What are the larger implications of this crime. So, over the next week or so, I will brainstorm these big questions, and from there--voila!--a plot of sorts will emerge for me. I will figure out anchor points, motivations, and subplots from there. Then I will start writing. Every time I hit a roadblock, I will just start the questioning process again, until I figure out the direction I need to take to move forward. So I will call my approach, Plot-Pantsing. What about you? If you are a writer, what approach do you prefer? As a reader, do you think you can tell which approach a writer took? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed