Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 As I'm finishing up my third historical mystery--The Masque of a Murderer--I found that I still had a few more things to research. In particular, what would commoners living in 17th-century London have known of chocolate, and how might they have experienced it for the first time? References to "chocolate" in England can first be found in the 1640s. Of course, "chocolate" as a substance had been around for several thousand years as Smithonian.com explains, originating in Mesoamerica. However, it did not find its way to Europe until the early seventeenth century, as one of the strange products imported from the New World. The word "chocolate" comes from the Aztec word "xocoatl," (or is it the Nahuatl word chocolatl?) referring to a bitter drink derived from cacao beans, with medical and health properties (for more about the etymology of the word, check out Oxford Dictionaries blog for ten facts concerning the word Chocolate... ). By the 1650s, several discourses on the "physicks" and health properties of chocolate were in circulation in London. In 1640, "A Curious Treatise of the nature and quality of Chocolate" by Antonio Colmenero, a Spanish"Doctor in Physicke and Chirurgery, was translated into English. More significantly, Henry Stubb published the far more substantial treatise on "The Indian Nectar" in 1662. We know too, from a collection of 1667 statutes from King Charles II that there were restrictions on who could sell chocolate: "And be it further Enacted by Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said first day of September, no person or persons shall be permitted to sell or retail any Coffée, Chocolate, Sherbet or Tea, without License first obtained and had by Order of the General Sessions of the Peace in the several and respective Counties,etc etc." This makes me reasonably certain that chocolate would have been sold at coffee houses, for those would have been the establishments likely to acquire such a license. It is unlikely that chocolate would have been sold at taverns or alehouses, at least in early Restoration England, due to the great dispute between those who sold wine and beer, and those who sold coffee. Chocolate might have been procured for medicinal purposes as well, although it is unclear to me--at least at this preliminary stage--whether it would have been actively prescribed by a physician. However, if the "Virtues" are to be believed (of course, that's if they are to believed), chocolate cures infertility, "ill complexion," digestive illnesses, consumption and "coughs to the lungs," "sweetens the breath," "cleaneth the teeth," "provoketh urine" and "cureth the stone." Apparently, this miracle drug also cures "the running of the reins," (the last a euphemistic biblical reference to venereal disease). Who knew? I have to surmise a bit here, on how popular chocolate truly was in Restoration London. But I think it's reasonable to assume, especially once sugar became a more common household good, that it would have been become popular fairly quickly. (Although it's also likely that it remained in the realm of the elite and wealthy, for quite some time.) But what do you think? England and Wales. A collection of the statutes made in the reigns of King Charles the I. and King Charles the II. with the abridgment of such as stand repealed or expired. Continued after the method of Mr. Pulton. With notes of references, one to the other, as they now stand altered, enlarged or explained. To which also are added, the titles of all the statutes and private acts of Parliament passed by their said Majesties, untill this present year, MDCLXVII. With a table directing to the principal matters of the said statutes. By Tho: Manby of Lincolns-Inn, Esq. 1667 Wing (CD-ROM, 1996) / E898

Wing / 2532:08

2 Comments

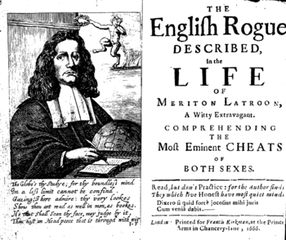

Watching my five-year old play hopscotch the other day got me wondering--where did this simple game come from anyway? I mean, if you think about it, doesn't HOP SCOTCH sound like it's connected to beer and liquor? Maybe the game came from kids watching adults stumbling out of taverns, under the influence, trying to hop on one foot while picking up stuff they'd dropped, without toppling over. Maybe kids mimicked the grown ups and over time--voila!-- the game of hopscotch emerged. (Okay, I'm writing this entry on a Friday night after a LONG week, so I could be reaching.)  so these guys played hopscotch? Indeed, a quick internet search informed me that no, hopscotch has nothing to do with alcohol (darn it! I thought I was onto something there). Instead, a jillion sites claim that the game actually derived from an ancient Roman military training exercise. Roman soldiers, wearing full body armor, would hop through a hundred-yard field in a precise way, to help improve their footwork in battle. (Cool, hey? Shall I stop here?) Wel-l-l-l, I'm always a bit skeptical of what I read on the internet. Especially since many of these sites seemed to be just parroting the same tidbit over and over without any evidence. And there didn't seem to be any evidence of the term before the seventeenth century. And then I found this fascinating bit of detective work carried out by the "Rogue Classicist." Here, he essentially traced the origins of the hopscotch myth--and yes, it is a myth--to a misunderstanding. Apparently, in 1870 a scholar sharing his findings in an archeology journal made an offhand comment to the effect that some ancient tiles and disks might be 'admirably suited to our modern game of hopscotch.' But someone else misunderstood, and made an erroneous leap--reading a link from ancient times to modern game that was not there. This misunderstanding was picked up, and repeated so many times that eventually it became "fact". Oh, and what's the truth of it all? Hopscotch, originally called "scotch-hop", was a game which probably emerged in seventeenth-century England (although similar games can be found around the world.) First mentioned in the Book of Games in the 1670s, Francis Willughby describes the game of "hopscotchers" in which children play with a little piece of lead on a floor with lines etched--or "scotched"--onto its surface. So, a game. However, if you prefer, we can rewrite the history of hopscotch once again. Just cut and paste my imagined origins of the game--you know, where kids were laughing at drunk grown-ups--and pass it off as fact. What do you think?  this MEANS something! After working through the copy edits of my first novel--A Murder at Rosamund's Gate--I must say, I really learned a few things. First, copy editors are amazing. Really. All this chicken scratch to the left actually means something important to the copy editing process. Delete! Insert! Move up! Move down! and my favorite, "AU," which is short for "Author, what the heck could you possibly mean by this passage?" I'm used to marking up student papers, but only the first few pages.So I was shocked--and frankly, a bit chagrined--to see that my entire manuscript was marked up from beginning to end, with characters and symbols I didn't recognize. (Thankfully, copy editors don't seem to share my grading philosophy: "Make 'em fix it themselves!") But I'm deeply grateful for her enormous help, and cognizant of how fortunate I am. Second, apparently, I don't use commas correctly. Nearly all my commas were eliminated in the editing process. This surprised me. Purdue's famous Online Writing Laboratory tells us there are 15 rules concerning the use of commas. Having had to memorize these rules as a grad student, I'd been reasonably confident in my ability to render a comma correctly. Yet, as I've learned, few of these comma rules hold true in fiction writing. Why such a marked difference in style? I suppose in fiction, the goal is to keep readers breathless, which won't happen if they have to stop at every comma speed bump. So my takeaway? Commas be damned!  those verbal tics are insidious! Third, I learned I have some terrible writing tics. Okay, I know the words "But," "However," "Yet," and "Actually" are not as disgusting as the tick pictured here, but they're equally insidious--crawling through my manuscript, clinging to my sentences-- refusing to be combed away under even the closest of scrutiny. Disgusting, I tell you! Disgusting! And so so SO hard to exterminate! See how many I've used in this post alone? But being aware of them is half the battle, right?  I don't edit with scissors anymore! Fourth, and more significantly, I also learned that continuity errors are extremely easy to make in the revising process. I can't remember if I've talked about this already but let me just say: Continuity errors are extremely easy to make in the revising process. (Ha! you see what I did there?) Seriously, I've discovered this problem the hard way. After I chopped out 10,000 words from the beginning and pushed the novel timeline back six months, I made some mistakes. These continuity errors also occurred, I think, when I cut a few minor characters (and reassigned their actions to other characters). Unless a writer is meticulous, which frankly I'm not, it's easy to make mistakes. This leads me to the fifth thing I learned: The spreadsheet is my friend! I'd heard writers talk about their "Bibles" (Nathan Bransford calls his the "Series Bible"), which contain all their character descriptions and quirks, key points, timelines etc. Never mind the term is a complete misnomer, the idea is sound. Systematically keeping track of stuff in a spreadsheet seems to be a particularly good idea now that I'm working on my second novel. This might give my Vice-President for Continuity Management (aka my alpha reader) a reprieve as well. And the sixth, more serious, point: As much as I think I've scrutinized my manuscript for historical inaccuracies, they seeped in anyway. "The Fire of London," my copy editor politely informed me, "began on September 2, which was a Sunday morning, not a Monday morning." No! this couldn't be true! She must not have understood how the Julian calendar worked. Ten days off the Gregorian calendar, beginning on March 26, blah blah blah I've talked about this before. Bottom line: there was no way I had it wrong. Confidently, I opened up my trusty historical date calculator, blithely went to September 2, 1666 and --Egads!-- found that the great calamity of London had indeed begun in the wee hours of a Sunday morning. I know my cheeks were a furious shade of red as I scrambled to reframe one of the most important scenes in my novel. It was hard work I wasn't expecting at this point, but I'm so grateful these errors were caught in the end.  shaping a novel--farrier style Which leads me to my seventh, most important, most nerve-wracking realization. The copy editing process means my novel--ten years in the making--is almost ready for the world! I'm no longer shaping this malleable object, hammering it, re-firing it, working it just so. It's almost ready! But the big question is...Am I? Murder at Rosamund's Gate  So if you're at that seventeenth-century dinner party that I mentioned in my last post, you'll want a few "merry jests, smart repartees, witty sayings, and a few notable bulls" to amuse and delight your friends (that is, if you want to transcend urine tricks and flatulence). (Not jokes though--apparently the word joque, from the Latin iocus "jest, sport, pastime'--had only just emerged in England in the 1660s, and was only just entering the seventeenth-century vernacular.) This particular jest-book, Humphrey Crouch's England's Jests Refin'd and Improved (1693), one of England's first such collections, offers equal opportunity digs at all manner of people: gentry, magistrates, royals, Quakers, Catholics, priests, Jews, foreigners, scholars, students, old people, young people, pregnant women, scolds, rakes, brothel-keepers, cuckolded husbands, criminals awaiting execution--you name it. Many jests were political or religious in nature but, as you might imagine, such humor doesn't always translate easily across three centuries (and English doesn't always translate to American. HA!) However, this one just amuses me. "A witty young fellow was try'd for his life, since his Majesties Restoration. And being caught, they told him he must be hang'd: But he pleaded in his own defence a long time; at last desir'd the Judge, That if he must be hang'd, he might be hanged after the new way that Oliver was, three or four years after he was dead." (The corpse of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell had been dug up and hanged posthumously two years after Charles II was restored to the English throne. Yup, as gross as it sounds.) And, I could skip the obligatory lawyer jest but I won't. "A certain person speaking unseemly words before a Gentlewoman, she ask'd him what profession he was of. Madam, says he, I am a civil lawyer. Alas, Sir, she replied, If Civil lawyers are such rude people, I wonder what other Lawyers are." Mwah ha ha! Civil lawyers. (Okay, fine. Maybe not that funny) Of course, I imagine bawdy humor will still translate best.... "Two friends meeting, one being overjoyed to see the other. Hark you Sir, said he, Between you and I, my wife's with child. Faith, cry'd the other, you're a liar, for I have not seen her this twelve months." (Awk-ward!) "A young woman, having married a great student, who was so intent on his studies, that she thought herself too little regarded by him, and one day when they were at Dinner with some Friends, she wished herself a book, that she may have more of her Husband's company. If it must be so, says her husband, I wish thou wert an Almanack, that I might change thee for a new one once a year." (Ouch!)  the witless cuckolded husband (with horns!) "One that had only been married but a week called her husband a 'cuckold,' which her mother hearing, reproved her: You slut, says she, do you call your husband cuckold already?And I have been married this twenty years to your father, and never darest tell him of it yet!" (Ah, the old cuckolded husband jest). So you tell me...how would this jest end? A cuckold, a magistrate, and a Puritan walk into a tavern...  Entrenched in intrigue I'm always fascinated by the way words seep into the English language. In honor of my Downton Abbey withdrawal and Florence Green (the last World War I veteran who passed away a few weeks ago at 111) AND because I recently wrapped up a class discussion on the Great War, I thought I'd say something about how WWI introduced some rather evocative--if heartbreaking--language into our vocabulary.  fashion from the trenches In 1914, Burberry was commissioned to create a new type of coat, the trench coat, that would allow British officers to stay both stylish and comfortable during the war (not sure how that worked out...) After the war, the coat became extremely popular, made even more so when it made its way to Hollywood. (Nowadays, the trench coat is so pervasive, I always wonder if anyone thinks twice about its origins.) Lots of phrases are still around, too, mostly from the terrible conditions soldiers had to face. "In a funk" (feeling dejected) may have referred to the (funky/smelly) holes in the trench walls where soldiers could stand to keep dry."Lousy" referred first to lice infested clothes, later to everything crummy. "Dig oneself in" (stick to one's ground, being stubborn) came from entrenching. To be "Up against the wall" (in a difficult spot) probably came from deserters' placed in front of a firing squad. (All a bit stomach-churning, really). Shell-shock--a kind of obvious one. And sadly, "basket case," a term for someone who's a bit screwed up, arose from the practice of transporting severely injured men in baskets.  Snoopy stayed out of the trenches Some, of course, came from the early aviation: "In a tail-spin," "joystick," "nose dive" --all essentially descriptive. "Hush-Hush" referred to top secret operations. And a "dud" (a failure) comes from an unexploded mine or shell. And of course, the very best. Snoopy, the World War I flying "Ace." An excellent pilot, he was the high card to play against the dreaded Red Baron. (Although, now, when I see Snoopy reenact the prolonged suffering of a lonely airman stationed in France, I find it quite disturbing.) What other vestiges from the Great War do we still speak and hear daily? You tell me!  _ When I was first writing Monster at the Gate, I toyed with the idea of writing the whole book in authentic seventeenth century prose. That idea lasted about two seconds. Partly because that trick's been done, you know, by actual writers from that time period, like Defoe. And partly because I thought readers might throw rotten tomatoes at me for writing in such a cumbersome manner (heck, I might throw them at myself). But mainly, it was because many seventeenth-century words and phrases don't translate readily today, and unless my editor lets me write a companion volume with glossary and explanatory footnotes, I don't think it would work (assuming I had the patience for such an endeavor, which I don't). For example, criminals and thieves created their own language, "cant," which was deliberately designed to hide their shadowy doings. Amazingly though, a few curious contemporaries, such as Richard Head, decoded this elusive criminal language in cant dictionaries (similar to modern slang dictionaries), basically as a public service to let their readers in on what the criminals were doing. So, for example, a thief might Bite the Peter or Roger (which our good Richard tells us means "steal the port-mantle or cloak-bag"), proceed to Tip the Cole to Adam Tyler ("give what money you pocket-pickt to the next party") , who might take it then to a stauling ken(a "house that wyll receaue stolen ware.") (I guess we'd say 'fence?'). Some phrases are even harder to translate. So, say a broadside depicts what happens to a criminal who is caught. It might read: “As the Prancer drew the Quire Cove at the Cropping of the Rotan through the Rum pads of the Rume vile, and was flog’d by the Nubbing-Cove.” Huh? Any guesses? No? Really? Well, according to J. Coleman's History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries (Oxford, 2004), that statement translates to: “That is, The Rogue was drag’d at a Carts-arse, through the chief streets of London and was soundly whipt by the Hangman.” You probably knew that. Awesome stuff! But I'm curious. Have you read any terrific (modern) books that were written completely in dialect? Did you find them hard-going? fun? or something in between? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed