Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.

1 Comment

Intrigued? Then check out my most recent post on A Bloody Good Read: Where Writers and Readers of Historical Thrillers Talk Shop  She probably writes reports... Every time my sleuths engage in detective work, I have to laugh a little. After all, as a non-detective I: *am a bit afraid of guns * am not exactly fluent in any language besides English and Kid *can't kick-box *would run screaming if I encountered a dead body *never ever would decide to track down a killer on my own or even with my favorite cop That doesn't mean, of course, I haven't always wondered what kind of spy I'd be.

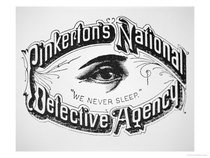

So I took the CIA personality Quiz. Turns out I'd be the non-glamorous, behind-the-scenes kind. (Hey, we need those too. Right? Right?). Take the test for yourself. Then come back and let me know how you did. Maybe we could form our own elite group of super spies. Apparently, I'll be the one taking notes.  17th c. detective of poisons A few weeks ago, I wrote about the first female literary sleuths, and since then I've since been wondering about the real first "detectives." I don't mean just any investigators of criminal activity, for surely, those have existed since time immemorial. But I was curious about when the term "detective" emerged as a recognizable title and/or occupation. The word does appear in the Early English Books Online as early as 1634. However, the word detective was not used as a noun, but rather as a verb, referring to the process of detecting. Specifically, the "famous chirugion [surgeon] Ambrose Parey" detective the effects of deadly poisons on the human body. Turning to my trusty Oxford Etymological Dictionary, I found that as a noun, "detective" was not used before before 1843. According to the Chambers Edinburgh Journal, "Intelligent men have been recently selected to form a body called the ‘detective police’‥at times the detective policeman attires himself in the dress of ordinary individuals." (12: 54). The word was later referenced in Willis' discussion of modern thief-taking in 1850: "To each division of the Force is attached two officers, who are denominated ‘detectives’" (C. Dickens, Househ. Words 13 July 368/1). Prior to 1850, those conducting investigations might have been called a searcher (1382), intracer (?a1475), inquisitor (?1504), inseer (1532), theif taker (1535) (my favorite, and the one I use!), peruser (1549) investigator (1552), tracer (1552), scrutineer (1557), examiner (1561), revisitor (1594), researcher (1615), examinant (1620), indagator (1620) (that's a great one!), ferret (1629), (another great one!), pryer (1674A), probator (1691), disquisitor (1766), grubber (1776), prober (1777), plant (1812), grubbler (1813), and plain clothes (1822). After 1850, additional colorful slang variants were used: Plainsclothesman (1856), mouser (1863), sleuth (1872), tec (1879), dee (1882) (shortened version of detective), sleuth-hound (1890), split (1891) (evolution of informer, turning against another person), hawkshaw (1903) (a character in a play), busy (1904), gumshoe (1906), (from the quiet stealthy shoes detectives began to adopt), dick (1908) (comes from a colloquial collapsing of 'detective'), and Richard (1914) (the common surname for nickname Dick). (Most of these expressions, it should be noted, came from criminal slang) And the first real person to be called detective? Well, it's hard to say...  In literature, the first detective is usually considered to be August Dupine in Edgar Allen Poe's Murder in the Rue Morgue (1841) (although I don't think he's referred to in the original version as a detective). Paul Collins, an associate professor at Portland State, a.k.a. the literary detective, has made the case for Charles Felix's detective in Velvet Lawn (1862) as the first of the genre. (On my list to read!). Others have argued for Inspector Buckett from Charles Dickens' Bleak House (1853), who may well have been based on a real private investigator that Dickens knew.  "We never sleep?!" Hey, that's my motto These works, demonstrating the emerging professionalism of detectives (or inspectors), clearly were influenced by larger nineteenth-century trends--most notably the ongoing reform efforts (which called for systematic, often covert, investigations into the corrupted and abusive practices found in factories, prisons, schools, hospitals, etc). Something else accompanied that change. As an investigator, the nineteenth-century detective was trying to systematically solve problems, using science to find solutions to the puzzles that plagued society. The "new" detectives were adopting a scientific, logical quality to the process of capturing criminals. The first known (and organized) private detective agency emerged in France in 1833. This occurred under the auspices of Eugène François Vidocq, a soldier turned privateer, who lived much of his early life on the run from from the law. (Apparently, Victor Hugo was so impressed with Vidocq that he based not one, but two, of his most important characters in Les Miserables--both Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert--on the man). Officially, however, at least in the U.S., Allen Pinkerton, a transplant from Glasgow, Scotland became Chicago's first detective in 1849. Soon after, he set up his famous Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the 1850s. Ultimately, this professionalization of the detective--with its' new emphasis on applying science, logic and technology to catching criminals--gradually reshaped the image of the investigator from "thief taker" to puzzle solver. These trends seem to have substantially influenced at least the first few generations of literary detectives, maybe more. Enter Sherlock, Poirot and all those who rely on "their little grey cells" to solve mysteries... (I do think the recent trend of paranormal crime solvers indicates the inevitable backlash, however, but that's another story). What do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed