credit: http://johnaconnell.com/ credit: http://johnaconnell.com/ The Brothers Grimm meet the Nazis? I'm delighted to have John A. Connell join me on my blog today. Here, he describes how a small city in Germany served as the dramatic backdrop for SPOILS OF VICTORY, his latest crime thriller set during the post-World War II era. The dark layered history of this small city is truly fascinating...  Garmisch-Partenkirchen Garmisch-Partenkirchen Garmisch-Partenkirchen would seem like an unlikely place to set SPOILS OF VICTORY, my latest crime thriller about murder and organized crime in post-WW2 Germany. The small German city—or large town, depending on how you look at it—could have been the setting for a fairytale in some far-off land. Nestled in a valley of the Bavarian Alps, its streets are graced with Hansel-and-Gretel houses and buildings with frescoes of pastoral scenes or local saints. Partenkirchen, first mentioned in 15A.D., was originally a Roman settlement, and one of its main streets still follows the old Roman trade route between Venice and Augsburg. Garmisch was settled 800 years later by a Germanic tribe. Separated by the glacier-fed Partnach river, the two towns remained separate until Hitler forced them to unite in 1935. Garmisch (as it is commonly called—much to the chagrin of the people of Partenkirchen) has been a favored winter resort since the late 1800s. The highest mountain in Germany is there, and the entire region is crisscrossed by world-famous ski slopes and dotted with placid alpine lakes. Hardly a promising location for murder and mayhem.  Werdenfels Castle...haunted? Werdenfels Castle...haunted? On the surface, that is, as Garmisch-Partenkirchen has had several dark periods. The first came in the 1600s, when the importance of overland trade routes dried up, causing Garmisch-Partenkirchen to come to near ruin. Privation, plagues, and crops failures led to witch-hunts, and in one two-year period 10% of the meager population was burned at the stake or garroted. Legend has it that Werdenfels castle, where the “witches” were imprisoned and executed, was so haunted that it was abandoned and torn down to build a church to drive away the evil that lurked within its walls. An even darker period descended on Garmisch with the Nazis’ rise to power. Göring went there to be treated for a bullet wound after Hitler’s failed putsch and given honorary citizen status by the city’s leaders. Hitler had wanted to buy farmland there for his mountain retreat, but the farmer wouldn’t sell, and Adolf ended up building his Eagle’s Nest in Berchtesgaden; a veritable who’s who of Nazis had called Garmisch their home away from home. The vestiges of the 1936 Winter Olympics still stand as monuments to Hitler’s dream of a 1000-year empire, though gone are the Nazi banners and signs forbidding Jews, or the elite Gebirgsjäger soldiers and swastika flag-waving fanatics. Indeed, it was a past so sordid that the town only commissioned it's archives in 1972—the people had no interest in remembering their Nazi past.  German soldiers of the Hermann Göring Division posing in front of Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1944 German soldiers of the Hermann Göring Division posing in front of Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1944 So, why did I decide on Garmisch-Partenkirchen for murder and mayhem? It was really by serendipity. My protagonist, Mason Collins, was actually the villain in a previous, defunct novel, with him committing murder in order to steal a cache of Nazi gold in occupied Germany. It was when I began researching Mason’s murderous backstory that I discovered that after WW2 the charming and beautiful Garmisch-Partenkirchen had become the Dodge City of occupied Germany! When the Third Reich collapsed, and the Allied armies were pushing into Germany from the west and east, Garmisch-Partenkirchen became the stem of the funnel for fleeing wealthy Germans, Nazi government officials and war criminals, retreating SS, and former French Vichy and Mussolini officials. And for the same reason it also became the final destination for Nazi-stolen art masterpieces, vast reserves of the Third Reich gold, currencies, precious gems, penicillin, diamonds, uranium from the failed atomic bomb experiments. After the war, all that became available for purchase on the black market. With millions of dollars to be made, murder, extortion, bribes and corruption became the norm. The promise of fortunes also brought in a multitude of scoundrels, scam artists, and gangsters. Add to this, tens of thousands of bored US Army soldiers ripe for temptation. The black market thrived, and gangs of deserted allied soldiers, former POWs, ex-Nazis, and corrupt displaced persons roamed the countryside. With the U.S. officials looking the other way or profiting from the activity, some gangs operated so openly that they were more like import-export companies. Here was this fantastic contrast: a Brothers Grimm fairytale town behind whose charming facades lurked mayhem and murder. It is said that truth is stranger than fiction, and, in this case, it has proved true. I even left some of the crazier stories out just to make seem more “real!” So, as it turns out, Garmisch-Partenkirchen was a great setting for a historical crime thriller after all!  From the official blurb: From the author of Ruins of War comes an electrifying novel featuring U.S. Army criminal investigator Mason Collins, set in the chaos of post-World War II Germany. When the Third Reich collapsed, the small town Garmisch-Partenkirchen became the home of fleeing war criminals, making it the final depository for the Nazis’ stolen riches. There are fortunes to be made on the black market. Murder, extortion, and corruption have become the norm. It’s a perfect storm for a criminal investigator like Mason Collins, who must investigate a shadowy labyrinth of co-conspirators including former SS and Gestapo officers, U.S. Army OSS officers, and liberated Polish POWs. As both witnesses and evidence begin disappearing, it becomes obvious that someone on high is pulling strings to stifle the investigation—and that Mason must feel his way in the darkness if he is going to find out who in town has the most to gain—and the most to lose…  John A. Connell is the author of Ruins of War and SPOILS OF VICTORY, the first two books in the Mason Collins series. He was born in Atlanta, where he earned a BA in Anthropology, and has been a jazz pianist, a stock boy in a brassiere factory, a machinist, repairer of newspaper racks, and a printing-press operator. He has worked as a cameraman on films such as Jurassic Park and Thelma & Louise and on TV shows including The Practice and NYPD Blue. He now lives with his wife in Madrid, Spain, where he is at work on his third Mason Collins novel. Visit him online at johnconnellauthor.com.

1 Comment

Probably one of the most frequently asked questions I get from people seeking to write historical fiction is this: How much research should I include in my historical novel? And my reply, which may sound more flippant than I intend, is just this: Enough to tell the story. I've written elsewhere about balancing historical accuracy and authenticity. So, I thought today I'd given an example of how I seek to have my characters interact with historical details, hopefully without just dumping my research on my readers. I could have picked any passage, but in honor of Easter, I picked an excerpt from my forthcoming novel, A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET. In this, scene Master Aubrey has just returned from selling pamphlets (unsuccessfully) on Maundy Thursday, (known in other parts of the world as "Holy Thursday.") There were a couple of factual details about Easter that I wanted to bring up in the scene. First, since the Middle Ages, there was a tradition in England that on Maundy Thursday, the monarch would give money to the poor and wash the feet of twelve poor people. [Indeed, while the etymology is not certain, the word "Maundy" may have come from the Latin world mendicare ("to beg.")] But we know from the diarist Samuel Pepys, in 1667, King Charles II opted against the practice that year, asking the Bishop of London to do it for him. Second, there had been an ongoing debate about the moveable date of Easter--some scholars of the time insisted that the date should be the same each year, similar to how Christmas was always on December 25. Third, in general, I wanted to allude to the fact that England was on a different calendar (the Julian Calendar) than Catholic nations like France and Italy, which had adopted the calendar created by Pope Gregory (the Gregorian Calendar). I couldn't use all the research I had at my fingertips, but I tried to work in a few of the more salient points within their trade as the printers and sellers of books. So you can see what details I managed to include...  John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 Master Aubrey laid his pack down. “I sold a few. I went to Whitehall to see the King wash the feet of the poor people, but the Bishop of London did it on his behalf.” The printer seemed a bit disgruntled. It had long been the custom for the monarchs of England to wash the feet of twelve men and women, as Jesus had washed the feet of the Apostles before the Last Supper. Having the Bishop of London take on the task instead of the king clearly irked him. Sometimes Lucy suspected the printer had Leveller sensibilities and liked it when the royals took on more mundane responsibilities. “Which pieces did you bring?” Lucy asked, changing the subject. In truth, she was always intrigued to know how the packs got decided. Master Aubrey had a knack for knowing what to sell to attract a crowd that she desperately hoped to learn for herself one day. “Could not very well sell murder ballads and monstrous births on Maundy Thursday, hey? Brought along John Booker’s Tractatus paschalis and John Pell’s Easter Not Mis-Timed. Too many of them, it seems. Only the sinners’ journeys, like the one you wrote about that Quaker, sold today.” He kicked the still-full bag, looking in that moment a bit like Lach, causing Lucy to hide a smile. A rare miss for Master Aubrey. Most people did not care how the date of the moveable holy day was affixed in the almanacs each year. Nor did they care why Catholic nations celebrated Easter and Christmas on different days than they did in England. I'm sure some readers might think that I have provided too much detail here, and other people think I have not offered enough. But, for me, this was "enough to tell the story."

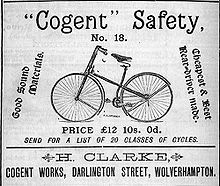

Writers are frequently enjoined to "write what they know," and my guest blogger today has certainly taken that message to heart. Edith Maxwell, author of the the forthcoming historical mystery, Delivering the Truth, features a Quaker midwife in 19th century New England. Edith is a Quaker, has taught childbirth classes, and lives in New England. So I guess she knows what she's talking about!!!  From the official blurb: For Quaker midwife Rose Carroll, life in Amesbury, Massachusetts, provides equal measures of joy and tribulation. She attends to the needs of mothers and newborns even as she mourns the recent death of her sister. Likewise, Rose enjoys the giddy feelings that come from being courted by a handsome doctor, but a suspicious fire and two murders leave her fearing for the well-being of her loved ones. Driven by her desire for safety and justice, Rose Carroll begins asking questions related to the crimes. Consulting with her friends and neighbors―including the famous Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier―Rose draws on her strengths as a counselor and problem solver in trying to bring the perpetrators to light.  Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used In my Quaker Midwife Mysteries, Rose Carroll is a midwife helping pregnant women give birth in the safest way possible - in the 1888 New England mill town of Amesbury. She’s twenty-four, as yet unmarried, and a Quaker. Rose is an independent businesswoman, unconventional both for going about her business on her bicycle and for being a member of the Society of Friends. Quakers have long been known for being unconventional, though, and New England Friends of the era even more so. Rose’s mother works tirelessly for women’s suffrage. Rose’s friend and mentor, the real John Greenleaf Whittier, was an outspoken abolitionist and supported equality among his fellow humans. Rose addresses everyone by their first name regardless of social class or occupation, and speaks using “thee” and “thy” as Quakers did, so she’s used to traveling outside certain norms. She’s also known for her honesty and clean living. Her clients trust her. Although there was a New England Female Medical College, which was a training school for midwives, Rose took the traditional route and apprenticed with Orpha Perkins to learn her trade. When the elderly Orpha retires, Rose takes over her business. The late 1880s is a fascinating period to write about because so much was changing, including the practice of midwifery and medicine. The germ theory of infection was known, so Rose is careful to wash her hands and keep the birthing chamber clean. A new hospital had been built across the river in the bustling seaport town of Newburyport only a few years earlier. Cesarean sections were done, but it was still a very risky procedure. And male doctors were starting to do deliveries, practicing obstetrics. I read that this practice increased in part because women working in factories were living away from their female relatives who would normally support them through the birth and postpartum period. The husband of one of Rose’s clients insists that his baby be delivered by a male doctor, but most of Rose’s pregnant clients much prefer having a woman attend them. I also read an account of a Massachusetts midwife being sued in 1905 for practicing medicine without a license. I haven’t heard of such accusations twenty years earlier, however. Of course, being a midwife makes Rose a perfect protagonist. She can go places no male police officer can – women’s bed chambers – and hears secrets the detective isn’t privy to, both during labor and at client visits. I know in earlier times midwives had a obligation to extract information from unwed mothers about the father of the baby and report him to the authorities, but I haven’t been able to unearth whether that practice still stood at the end of the nineteenth century. (See Sam Thomas' excellent post on the role of midwives in 17th century England, for example. -SC)  Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission I’m delighted to follow Rose around the streets of my town where many of the buildings of the late 1880s still stand, including the Friends Meetinghouse where she and Whittier worship, and write down her adventures.  Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries (Midnight Ink) and the Local Foods Mysteries, the Country Store Mysteries (as Maddie Day), and the Lauren Rousseau Mysteries (as Tace Baker), as well as award-winning short crime fiction. Her short story, “A Questionable Death,” is nominated for a 2016 Agatha Award for Best Short Story. The tale features the 1888 setting and characters from her Quaker Midwife Mysteries series, which debuts with Delivering the Truth on April 8, 2016. Maxwell is Vice-President of Sisters in Crime New England and Clerk of Amesbury Friends Meeting. She lives north of Boston with her beau and three cats, and blogs with the other Wicked Cozy Authors. You can find her on Facebook, @edithmaxwell, on Pinterest, and at her web site, edithmaxwell.com. Want to know more about the original Quakers from 17th century England? Check out my discussion of the political activities and writing of Quaker women. Or this post on their last dying speeches.

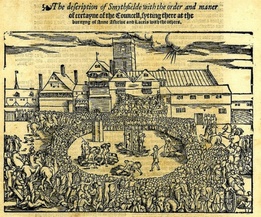

I am delighted to be joined on my blog today by Bridgette R Alexander, author of SOUTHERN GOTHIC: A Celine Caldwell Mystery (to be released March 15, 2016). I had the pleasure of reading Bridgette's debut novel a few weeks ago, and I was struck by the authenticity of her main character's voice. I thought that her amateur sleuth, Celine Caldwell, came across as a "real" teenager--which is actually not an easy feat. So I asked Bridgette to talk about her experience with writing YA fiction. SC: Bridgette, why did you decide to write YA? BA: I grew up loving ABC’s after school specials. What I liked about them was that each story was told from the perspective of a teenage girl, usually, and it gave me a sense that I wasn’t alone in my day-to-day struggles as an adolescent. By that I mean, adolescence is a tough place to be in and you’re there for a long period of time. You are caught between two worlds, one world of a child – its only two or three years ago you were taken to the junior’s section of a department store and your mother was selecting clothes for you. Your world was pretty much being established by the adults around you. Then, there is this other world of [looming] adulthood. Total and complete agency – by you; at 14 or 16 you can make some decisions for yourself, at least what you’re going to wear and who your friends are; and the biggest of all – eros – your attraction and your identity. For me, those moments were paramount. So much so, that I like to view being an adult as an old-kid with benefits. SC: Are there any authors who particularly inspired you? BA: I was introduced to some of my all-time favorite authors when I was in the 7th grade: Mark Twain; John Steinbeck; James Baldwin; William Faulkner; Tennessee Williams; and Hermann Melville. I loved how those works transformed me into the worlds the authors created and caused me to think about the world I inhabited. Then on my own I found the works of other authors and also fell in love with them: Jackie Collins; Harold Robbins; Judith Krantz; I know, I know…they are not exactly children’s authors, but I so loved their works. Mystery and thriller writers I just adore – Agatha Christie, Steven King Joyce Carol Oates and Sarah Paretsky; and of YA writers I really love the work of Sarah Dessen, I love her stories. She totally captures the voice of a strong, independent teenage girl. There are sooo many writers I love, these are just a few of them. SC: What do you enjoy most about writing YA? BA: I like seeing the world fresh again. SC: What kinds of challenges have you faced in writing YA? BA: In writing…not so much. At the moment when I could visualize Celine Caldwell and her life, then her all of her friends and their lives, it was like a motion picture – fluid, moving, colorful and rich with characters. For me it’s been more of a head-game I've had to overcome. The notion of the solitary artist…alone in his or her misery as the only path to creativity is a romantic construct. One that at the on-start of developing and trying to write the Celine Caldwell Mysteries, I thought I was bound to adapt. It was difficult. As a scholar my life was writing among other scholars; sharing my works and dissecting that work with other scholars. As a scholar and thinker I led a fully engaged life. Only in the archives and the library stacks would I actually be in solitude. When I adapted to my writing the engaged-life I was used to, it felt real and true. I am creating characters, developing scenes, structuring the chapters, going back and forth with my editors. SC: How do you make sure your characters are “authentic”? In terms of voice, dialogue, mannerisms? BA: At the beginning of writing Celine Caldwell Mystery series, I organized a teen council made up of girls between the ages of 12 and 18. We’d meet and I’d give them a Celine-Scenario and ask them what would they do or if Celine’s actions were authentic for a teenager, and not just as a teen being driven by an adult. It was important for me to remove myself as much as possible from the equation of Celine Caldwell, 16 year old art world sleuth. Now that’s more of the technical work I’ve done, compared to the easy going fun time I make time for in talking and listening to teen voices. I continue to spend a good deal of time with teenagers because I strongly believe from where I stand it easy for me to “slip” back into the voice and mannerism of an adult person. SC: I know you have a daughter...did you learn anything from her that helped you write your book, or offer insight into the teenager experience? BA: My daughter is the inspiration behind Celine Caldwell. I created [Celine] when my daughter was a newborn. I’d often imagine her future -- how would she relate to the world; what would she look like once she becomes a teenager. My daughter’s life is very different from my upbringing. Her life looks more like the character Celine Caldwell’s with the big exception, my daughter has a doting mother and father. SC: What advice if any would you offer someone interested in writing YA? People or writers hear this a lot…but it stands to be repeated. Write what you know and do it from your soul.  Bridgette R. Alexander is a modern art historian. She received her graduate training in 19th century French art history at the University of Chicago. Alexander worked with some of the world’s greatest museums in New York, Paris, Berlin and Chicago and developed art education programs; curated exhibits; she has taught and published in art history. She’s been featured in a number of publications including, Art + Auction Magazine; the Wall Street Journal; and the Washington Post. SOUTHERN GOTHIC is her debut novel. Alexander currently lives in Chicago and when not writing, she takes her husband, daughter and friends on midnight tours of the cultural institutions. Visit her website (http://celinecaldwell.com).  Civitas Londinum, 1561 Civitas Londinum, 1561 Like the lost River Fleet, another location in London that has long intrigued me is the infamous Smithfield market; a site of enormous contrasts: executions and extreme devotions, torture and merry-making. In the Middle Ages, Smithfield--"a smooth field" to the north of London's walls--was a natural place for jousts, tournaments, and the selling and butchering of livestock. Conveniently (!), animal waste from the market could be dumped into the River Fleet, which flowed into the Thames. It’s original origins as a place where livestock could be bought and sold, can be seen in the vestiges of its street names (e.g. Cow lane, Cock lane).  Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Not surprisingly, Smithfield, like most great open communal spaces was used for greatly varied purposes, including: Public torture: Over the centuries, many criminals—particularly those accused of treason—were tortured. One of the most famous was William Wallace (“Braveheart”)- - a twelfth century hero of the Scottish people. Drawing and quartered was the preferred method, and perhaps castrated as well (but studio executives probably thought movie audiences couldn’t stomach Mel Gibson undergoing that particular humiliation.)  Public executions: While Smithfield was a regular site of hangings and burnings for centuries, under Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary” to her detractors), quite a few Protestant dissenters were publicly burned as heretics. [Interesting side note: According to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, the “Marian Martyrs” would ask that their hands not be bound and their wood pile would consist of the greenest wood, so that their plaintive laments and prayers would last longer.) The burnings of these men and women were collectively referred to as “The Smithfield Fires.” Merry-making and Fair-going: Every August until the mid-seventeenth century, St. Bartholomew’s fair would be held at Smithfield. Originally it was supposed to be only three days of merry-making, but by the 17th century the fair was lasting over two weeks. Check out this advertisement for the entertainment to be had at the “Plow Music Booth” in 16xx:  Anon (1679) Anon (1679) “At the Plow-Music Booth in Smith Field Rounds, (a Red flag being on the Top) during the Time of Bartholomew-Fair, you may be entertained with excellent sports, [such as] Antique dances, entries, cerebrands and jigs, a little girl about 6 years old who danceth with two naked rapiers at her throat, to the admiration of all that ever see her…. With good Wine, Cider, Mum and Mead, and good music for the accommodation of those who are inclined to mirth.”  Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Or of course, for "all single men and bachelors," there was also an ongoing "auction of whores," which--as Michael Altham (1691) joked--contained, “a curious collection of painted whores, cracks, night-walkers, newgate-nappers, bridewell-workers, ladies of pleasue, cart-dancers; with other such dissembling pick-pocket cheats, some pox’d, some clap’d, and some quite rotten and ready to fall in pieces.” Underlying this bill, however a real fear of disease and pollution that seemed to occur whenever so many people were brought in such close proximity. King Charles I tried to cease the Fair on several occasions during his reign. In 1637, he issued a proclamation for putting off the Bartholomew Fair, and a similar fair in Southwark:  Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 “Whereas his Majesty hath taken special care and given several directions, that the usual assemblies and concourse of people might be omitted and forborne, the better to prevent the danger and increase of the infection: Yet finding that the plague is dispersed in sundry places in and near the City of London, his majesty in pursuance of those direction and out of his continual care of the safety of his subjects in general, and of the said city in particular, and to cut off all occasions that may conduce to the further spreading of the sickness, doth hereby declare his royal will and pleasure for the putting off this next fair…” This was only a temporary halt to such festivities; only Cromwell was able to completely stop the fun. The Fair, like all other such festivals, was banned under his regime, only to be restored in 1666 with the Restoration of the fun-loving Charles II.  Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Today, there is little indication of the mass executions and torture that occurred here, although Smithfield Market—now called the Central London Market—is the largest of its kind in London, and one of the largest in all of the European Union. But like the River Fleet, the Smithfield grounds are another part of secret London. |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed