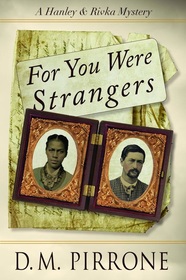

I'm delighted to be joined today by D.M. Pirrone, author of the Hanley & Rivka mystery series (Allium Press). From the official blurb: On a spring morning in 1872, former Civil War captain Ben Champion is found dead in his Chicago bedroom, a bayonet protruding from his back. His death uncovers hidden truths best left buried, that still threaten powerful men. Defective guns sold to the Union army, an 1864 conspiracy to turn Chicago into the capital of a Northwest Confederacy, a former slave passing for white, an escaped Confederate guerrilla bent on revenge...any of these might have led to Champion's murder. Hanley and Rivka race to solve the crime before the secrets of bygone days claim more victims.  D.M.Pirrone D.M.Pirrone As writers of historical fiction, we must still relate to our readers today. What are some of the things from “back then” in your books that have resonance here and now? Corruption, in politics and law enforcement, comes immediately to mind, of course. I’m writing about Chicago in the 1870s, so that’s a no-brainer! Poor Frank Hanley, my Irish detective, is one of the few honest guys in a system that rewards those who go along to get along—he has to deal with bought politicians and corrupt fellow cops who are either just as bad as the “bad guys” or too willing to turn a blind eye. In both of the Hanley & Rivka mysteries so far (Shall We Not Revenge and For You Were Strangers), Hanley has run-ins with a particularly dirty superior officer, Captain Michael Hickey. Hickey was a real person in the Chicago Police Department, and well known for crooked dealing, but no one could ever prove anything. He kept getting kicked upstairs rather than drummed out of the force, which poses an interesting problem—I would love to have Hanley take Hickey down, but history says I can’t. At least, not exactly… Another thing that resonates is injustice against the poor, masquerading as morality. This is a major theme of Shall We Not Revenge, which takes place just after the Great Chicago Fire. Contributions to the stricken city—money, food, clothes, blankets, even books for the library we didn’t have!—were sent from around the world, but distribution of aid was taken from the City Council and given to the Relief and Aid Society, a private organization run by prominent businessmen. These guys set up a system of what was then called “scientific charity”—meaning, a way of making sure aid went only to the so-called deserving poor, and even that, for the briefest possible time. The Aid Society sent out legions of volunteers, many of them well-off society women, to interview those who applied for aid, and decide on the basis of a single visit whether or not each person or family was morally worthy of help.

Did these people really need aid, or were they lying malingerers? Would they use the assistance given them to get back on their feet, or simply mooch off the public? The assumption was that the poor were mostly moochers by nature, the “47 percent” of their day, who didn’t want to work or improve themselves. Giving them aid only encouraged their natural sloth—particularly the Irish, who were seen as lazy drunkards and (as Catholics, mainly) inherently unable to assimilate into Protestant America. Sound familiar? Hanley has to deal with this directly, when his mother requests aid funds to buy a new sewing machine so she can earn a living again as a seamstress. It shocked me to learn that the Relief and Aid Society kept $600,000 worth of aid, smugly confident that they’d reached all the “truly needy” cases in Chicago with only a small portion of the donations sent to the city. For You Were Strangers takes on another hot-button current issue—racial and ethnic divisions, and the whole question of who “belongs” or doesn’t. Not to give too much away, but Rivka Kelmansky’s brother Aaron—who left home ten years earlier to fight in the Civil War, and wasn’t heard from after it ended—turns up on Rivka’s doorstep with a mulatto wife and stepson. He’s been on a long, strange trip, and is seeking sanctuary from danger for himself and his Christian family members among the observant Jewish community he left so long ago. Another character in the book is passing for white, and is forced by events to come to terms with that. There’s also a major character from the South, formerly wealthy and pampered, whose world turned upside down when war came, and who doesn’t succeed very well at finding a new place to belong, with ultimately tragic consequences. So it’s a rich stew of issues that mattered back then as much as they do now.

0 Comments

|

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed