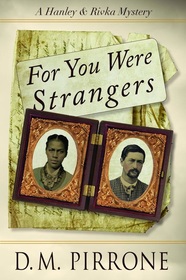

I'm delighted to be joined today by D.M. Pirrone, author of the Hanley & Rivka mystery series (Allium Press). From the official blurb: On a spring morning in 1872, former Civil War captain Ben Champion is found dead in his Chicago bedroom, a bayonet protruding from his back. His death uncovers hidden truths best left buried, that still threaten powerful men. Defective guns sold to the Union army, an 1864 conspiracy to turn Chicago into the capital of a Northwest Confederacy, a former slave passing for white, an escaped Confederate guerrilla bent on revenge...any of these might have led to Champion's murder. Hanley and Rivka race to solve the crime before the secrets of bygone days claim more victims.  D.M.Pirrone D.M.Pirrone As writers of historical fiction, we must still relate to our readers today. What are some of the things from “back then” in your books that have resonance here and now? Corruption, in politics and law enforcement, comes immediately to mind, of course. I’m writing about Chicago in the 1870s, so that’s a no-brainer! Poor Frank Hanley, my Irish detective, is one of the few honest guys in a system that rewards those who go along to get along—he has to deal with bought politicians and corrupt fellow cops who are either just as bad as the “bad guys” or too willing to turn a blind eye. In both of the Hanley & Rivka mysteries so far (Shall We Not Revenge and For You Were Strangers), Hanley has run-ins with a particularly dirty superior officer, Captain Michael Hickey. Hickey was a real person in the Chicago Police Department, and well known for crooked dealing, but no one could ever prove anything. He kept getting kicked upstairs rather than drummed out of the force, which poses an interesting problem—I would love to have Hanley take Hickey down, but history says I can’t. At least, not exactly… Another thing that resonates is injustice against the poor, masquerading as morality. This is a major theme of Shall We Not Revenge, which takes place just after the Great Chicago Fire. Contributions to the stricken city—money, food, clothes, blankets, even books for the library we didn’t have!—were sent from around the world, but distribution of aid was taken from the City Council and given to the Relief and Aid Society, a private organization run by prominent businessmen. These guys set up a system of what was then called “scientific charity”—meaning, a way of making sure aid went only to the so-called deserving poor, and even that, for the briefest possible time. The Aid Society sent out legions of volunteers, many of them well-off society women, to interview those who applied for aid, and decide on the basis of a single visit whether or not each person or family was morally worthy of help. Did these people really need aid, or were they lying malingerers? Would they use the assistance given them to get back on their feet, or simply mooch off the public? The assumption was that the poor were mostly moochers by nature, the “47 percent” of their day, who didn’t want to work or improve themselves. Giving them aid only encouraged their natural sloth—particularly the Irish, who were seen as lazy drunkards and (as Catholics, mainly) inherently unable to assimilate into Protestant America. Sound familiar? Hanley has to deal with this directly, when his mother requests aid funds to buy a new sewing machine so she can earn a living again as a seamstress. It shocked me to learn that the Relief and Aid Society kept $600,000 worth of aid, smugly confident that they’d reached all the “truly needy” cases in Chicago with only a small portion of the donations sent to the city. For You Were Strangers takes on another hot-button current issue—racial and ethnic divisions, and the whole question of who “belongs” or doesn’t. Not to give too much away, but Rivka Kelmansky’s brother Aaron—who left home ten years earlier to fight in the Civil War, and wasn’t heard from after it ended—turns up on Rivka’s doorstep with a mulatto wife and stepson. He’s been on a long, strange trip, and is seeking sanctuary from danger for himself and his Christian family members among the observant Jewish community he left so long ago. Another character in the book is passing for white, and is forced by events to come to terms with that. There’s also a major character from the South, formerly wealthy and pampered, whose world turned upside down when war came, and who doesn’t succeed very well at finding a new place to belong, with ultimately tragic consequences. So it’s a rich stew of issues that mattered back then as much as they do now. What’s the biggest challenge you've faced in writing historical fiction?

There’s the obvious one, how to balance all the great stuff I find in my research with the need to keep the story moving. The temptation to “info dump”—lay out a huge chunk of background information on some historical event that plays into my story line—can be enormous, especially when readers have to know about it in order for my characters’ actions to make sense. That turned out to be a major challenge in For You Were Strangers. Part of the plot revolves around the Northwest Conspiracy, an attempt by Southern sympathizers to take over Chicago in 1864 and turn it into the capital of a Northwest Confederacy. The conspiracy fizzled out, and nowadays most people don’t know about it—but it was a big deal to Chicagoans at the time. They saw it much as we do nowadays when we hear rumors of some terrorist plot or other, whether or not anything actually happens. Another challenge can be to get the mindset of an earlier time across to modern audiences, especially when that mindset includes less pleasant world views—racism, sexism, and so on. One thing Hanley struggles with in For You Were Strangers is the underlying racism so common among whites at the time…not the vicious hatred of black people that we so often think of as racism, but the more insidious assumption that blacks are naturally inferior to whites. Hanley isn’t completely free of this, and yet I want my readers to like him, so it was tough to find the right balance. What’s your writing process like? On a good day—meaning, I don’t have a big editing project or an audiobook to record, and I manage to avoid the temptations of Facebook and reading blogs—I generally spend my mornings writing or outlining, or both. I’ve tried writing with an outline and without one, and I find I need to plan at least a few chapters ahead, or I flail around and get lost. Usually, somewhere around the middle of a book, I’ll get a better idea than the one in my outline—my subconscious is way smarter than me—and I’ll end up tossing parts of my old outline and reworking the rest to fit the new plot events. Sometimes, when I have a better idea or I get some especially great feedback from my writers’ group, I’ll shift direction and then have to go back and tweak things in prior chapters for the new direction to make sense. That can be a pain, but it’s also an interesting challenge in figuring out what to keep and what to jettison. The great thing about outlining is, I talk it out to myself before I write anything down—which means I can work on my book and get domestic chores done at the same time, when there’s no one else around to wonder if I’ve gone a little crazy. What’s the weirdest, or most unexpected, historical fact that you’ve ever come across while researching for a book? One unexpected thing I came across in researching 1870s Chicago is that the Irish weren’t yet a major power in the city. I grew up thinking of the Irish as basically running things—just go down the list of prominent Chicago politicians, judges and so on, and you find Irish name after Irish name, Daley, Madigan, et cetera. But in 1872, the Irish were still underdogs—distrusted, looked down on, discriminated against. They’re just short of critical mass, when they’ll start to become a powerhouse in Chicago politics and law enforcement. So Hanley knows firsthand what discrimination feels like. An oddball story I love is one I ran across in City of the Century, by Donald L. Miller. There’s a chapter where he talks about The Sands, a red-light and gambling district that used to be down by the lake shore…and of course, Chicagoans got their water principally from Lake Michigan, which wasn’t as filthy as the Chicago River. This included the saloons, and the water wasn’t filtered at all, just sucked up straight from the lake. Miller has a story about an off-duty Chicago cop who arrests a saloon owner in The Sands for watering the beer—he discovered it when he raised his glass and spotted a minnow swimming in the liquor. I’m definitely giving Hanley that moment in one of my books. I just need to find the right scene. Author Bio D. M. Pirrone is the nom de plume of Diane Piron-Gelman. Her historical novel Shall We Not Revenge (Book 1 of the Hanley & Rivka Mysteries, Allium Press of Chicago, 2014), was a Kirkus Prize nominee and a Notable Page-Turner in the 2014 Shelf Unbound Indie Novel competition, and earned Honorable Mention for traditional fiction in the Chicago Writers’ Association 2015 Book Awards. Book 2 in the Hanley & Rivka series, For You Were Strangers, comes out on December 15th from Allium Press. Ms. Piron-Gelman is also the author of No Less In Blood (Five Star/Cengage, 2011). A Chicago native and history buff, she is a member of Mystery Writers of America, Sisters in Crime Chicagoland, the Chicago Writers Association, and the Society of Midland Authors. Check out her website at www.dmpirrone.net.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed