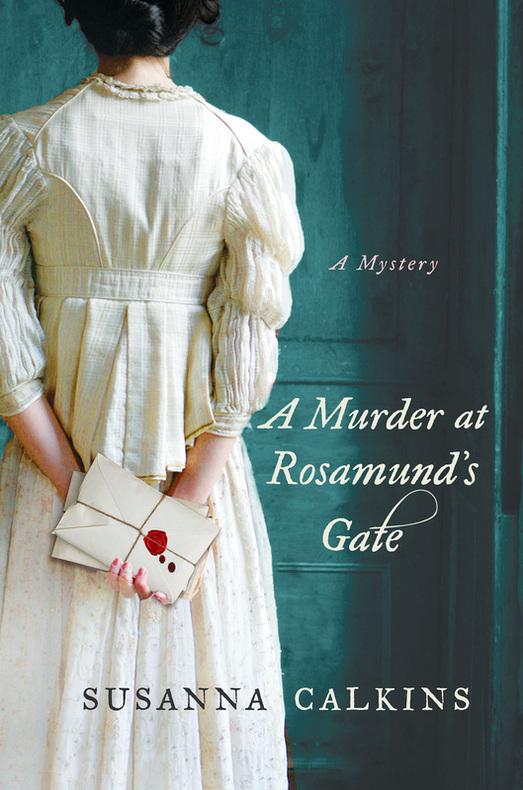

I can't tell you how excited I am to see the cover of my first novel!!! A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. I think the artists at Minotaur captured the essence of my story beautifully. The opening (and closing) images of my novel are of Lucy standing at a door. There are some other clues about the story tucked away here, but you'll have to read the book to discover them for yourselves!!!

40 Comments

Yes, it's true! We've changed the title of my first novel to.... drum roll!!! drum roll!!! drum roll!!! A Murder at Rosamund's Gate My original title, Monster at the Gate, was deemed by the good people at Minotaur/St. Martin's to sound a little too harsh, a little too supernatural--and more importantly--a little too different in style from the type of book I had actually written.

I get that, actually. In one of my first blog posts, I talked about how the word "monster" was understood in seventeenth-century England, back when it didn't carry the supernatural "Frankenstein's Creature" connotation that it does today. But you know what? I love my new title. I think it captures the essence of my book better than the first title did. And hopefully, you'll see why, when my book comes out in early 2013. For now, you might imagine strolling through the beautiful garden pictured above. Birds, trees, seventeenth-century stonework...and oh no! a body...  Anne Bonny, pirate, defying convention Hearing all the talk about piracy recently makes me think of my own days as a pirate. No, I was no Mary Read or Anne Bonny, two eighteenth-century women who disguised themselves as men in order to serve on a pirate ship. (But seriously, how cool were they? For several years they plundered and stole with the best of them...although of course they were publicly tried as pirates--and for defying conventions for women). But in the 90s, I did pull a short stint aboard the Golden Hinde, the museum replica of Sir Francis Drake's ship that circumnavigated the globe, currently dry-docked in the Thames, near London Bridge.  Golden Hinde (with an "e"!) in London During the week, I was a tour guide--ahem, costumed educator--for tourists and school groups, while on the weekends we ran pirate parties and living histories. We dressed in sixteenth-century sailor garb, which is not as glamorous as you might think. (In fact, once when I was taking my 'tea break' outside the nearby ruins of Winchester palace, a tourist offered me half a sandwich. Yup, she thought I was homeless.) Despite being a certified landlubber, I learned about ratlines, scurvy, gun drills and barber surgery (so gross, but so cool), swabbing the deck (much less cool) and a little tiny bit of nautical stuff, like turning the capstan, moving the yardarm, and of course some random pirate ditties. I was even hoisted once along the yardarm by the master rigger, a nauseating experience that gave me nightmares for some time. I got to talk about weevils, "powder monkeys" (the boys who carried gun powder would sway with the listing ship, looking like monkeys) , and the origins of such phrases as "loose canons" (cannons had to be secured on gun deck), "batten down the hatches" (that one's literal still, right?), and "freeze the balls of a brass monkey." (The last not so naughty as you might think). The best part? We all had to take turns on ship watch, sleeping in Francis Drake's own captain's cabin, while St. Paul's Cathedral gleamed across the Thames. Easily one of the most gorgeous views in London. (The crew and I also spent a lot of time playing sardines among the barrels, and 'tippling down the hatch' but that's entirely another story.) For me, it was a bit of a lark, something wonderful to support me while I worked in London's archives. And Bankside--where the Golden Hinde and Shakespeare's Globe are located--came to feature prominently in Monster at the Gate. I always wondered, though, what it would have been like to have been a real pirate--to have run away from home; to have shunned tradition, convention and stereotypes. Although maybe a few days living among rats, weevils, sickness, and 70 other unwashed bodies might have cured me of that romantic impulse. (Not to mention I think I'm a bit adverse to violence and plundering). But what do you think? Could it have been the pirate life for you?  _ When I was first writing Monster at the Gate, I toyed with the idea of writing the whole book in authentic seventeenth century prose. That idea lasted about two seconds. Partly because that trick's been done, you know, by actual writers from that time period, like Defoe. And partly because I thought readers might throw rotten tomatoes at me for writing in such a cumbersome manner (heck, I might throw them at myself). But mainly, it was because many seventeenth-century words and phrases don't translate readily today, and unless my editor lets me write a companion volume with glossary and explanatory footnotes, I don't think it would work (assuming I had the patience for such an endeavor, which I don't). For example, criminals and thieves created their own language, "cant," which was deliberately designed to hide their shadowy doings. Amazingly though, a few curious contemporaries, such as Richard Head, decoded this elusive criminal language in cant dictionaries (similar to modern slang dictionaries), basically as a public service to let their readers in on what the criminals were doing. So, for example, a thief might Bite the Peter or Roger (which our good Richard tells us means "steal the port-mantle or cloak-bag"), proceed to Tip the Cole to Adam Tyler ("give what money you pocket-pickt to the next party") , who might take it then to a stauling ken(a "house that wyll receaue stolen ware.") (I guess we'd say 'fence?'). Some phrases are even harder to translate. So, say a broadside depicts what happens to a criminal who is caught. It might read: “As the Prancer drew the Quire Cove at the Cropping of the Rotan through the Rum pads of the Rume vile, and was flog’d by the Nubbing-Cove.” Huh? Any guesses? No? Really? Well, according to J. Coleman's History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries (Oxford, 2004), that statement translates to: “That is, The Rogue was drag’d at a Carts-arse, through the chief streets of London and was soundly whipt by the Hangman.” You probably knew that. Awesome stuff! But I'm curious. Have you read any terrific (modern) books that were written completely in dialect? Did you find them hard-going? fun? or something in between? When I teach history, I always ask my students to view every "fact" as relative and subject to interpretation. Inevitably, someone will ask: "Well, what about dates? Those are facts." But dating and calendar systems vary widely, and may not be consistent across different groups of people.

I've been thinking about this recently as I struggled with the timeline of my own novel. Monster at the Gate begins a few months before the plague struck London in the 1660s. I start the novel on Shrovetuesday in February 1665 (a crazy strange day before Lent) and end with the Fire of London the following year (September 1666). Two clear beginning and ending dates, spanning about nineteenth months in total. Easy enough? NO! As I was writing, I kept running into odd inconsistencies with the historical records I was using (such as Pepys' Diary), trying to double-check details. I kept finding that Tuesdays should have been Sundays, or that Easter had occurred at a different time than I expected. I knew that historical records would say 1664/1665 or 1665/1666, but I couldn't remember the exact details of how contemporaries kept time. (MUCH GNASHING OF TEETH!!!!) Finally, I sorted it out. England was still on the Julian Calendar (which had been adjusted for a missing ten days), rather than moving to the Gregorian Calendar used by most of Europe (it did not reform its calendar until 1752). To make it even more confusing, the Julian Calendar year starts on March 26, not January 1. But luckily I found a historic date calculator to help me keep it all straight. So, my book technically starts on Feb 7 1664, and ends September 3, 1666, and that's still only nineteenth months. You do the math! But I'm wondering if it will confuse my readers if they think the book is starting in 1664, when by today's modern calendar, it would actually be 1665. What do you think? "Monsters" in seventeenth-century England were funny sorts--not like today's zombies or even Frankenstein's creature--but rather aberrations of humanity. Real human beings who, like my antagonist in Monster at the Gate, had crossed society's lines--committed murder or other unspeakable acts. Their humanity was restored only by execution--usually by public hanging.

(Ironically, the early modern crowds who gathered to watch these executions--men, women, and children who cheered on the criminals' grim ends--were not themselves considered to be monsters, despite their bloodlust and fascination with the gallows. But hey, people aren't always consistent, are they?) Booksellers and printers understood and exploited these sentiments, tapping into the public's fears, passions, and anxieties. Long before modern tabloids sensationalized criminal activity, early modern woodcuts, ballads and chapbooks conveyed to their readers 'true accounts' of each monstrosity, offering sordid and titillating details of the crime, the victim's last hours, and the monster's motivations. Implicit in many of these accounts was a warning--less to future victims, and more to society at large--that monsters walked among them. Though masked and disguised as humans, their monstrous nature would out. Woe to the community who did not catch and put an end to them! So when reading these accounts, I always wondered what parts of the sensationalized accounts were true, what was contrived, and most of all--Who were these monsters, really, when they weren't being monsters? The first image I had for Monster at the Gate was dreamlike, cruel--and a bit of a mystery cliche, although I did not realize it for years. I'd been pouring through woodcuts and broadsides-- researching gender patterns in domestic homicide--and I was struck by the same story that appeared again and again. A woman, stabbed in a secluded glen, discovered with a letter in her pocket. The letter would say something like 'Meet me at the secluded glen. I must see you.' And then it would be signed, 'L.J.' or something like that. The townspeople, the constable, everyone would scratch their heads--'Who was the monster? Who could have killed her?'

Huh? Was it possible that a whole community could be so naive? So gullible? I mean, there was a signed note from L.J.! Or was this just some sort of early literary trope that booksellers created to sell their wares? Either way, the story was not just sad, but incomplete. In some ways, MATG became the answer to the questions that never got asked--Who was this woman? Had she been excited when she met her murderer? Why the heck hadn't she been more suspicious? And most important of all--how could she get the justice she deserved? The image of that woman stayed with me for years, eventually becoming the prologue--until I learned that prefaces are pretty much despised by agents, editors, and readers alike. So ironically, my inspiration for the novel will never make it to publication. Re-reading it now, I think it was right to cut the preface. Yet, in my mind, this image will always remain pivotal for me. So I thought I'd share it here, both to share my original thinking, and to show why it won't make it to print. The young woman stumbled through the long grasses, squinting in the moonlight, trying to find the path. She had not dared to steal a lantern, and now she lamented her folly. Her long skirts caught on a branch, and she tugged impatiently at her red embroidered sash. Hearing a twig crack behind her, she whirled around. Recognizing the shadowy figure before her, she relaxed. But still she was puzzled. “What are you doing here?” She asked, panting slightly. “Have you a message?” The glint of a shining knife stopped her. Too late she realized her assailant’s intention. A quick thrust, and the blade ripped inside her. Brutal, fast, she barely had time to react. A hand clapped tightly over her mouth, muffling her dying sighs. Her struggles ceased, and her body grew limp in her captor’s arms. A moment later, her body fell to the soft ground. Clouds glided before the moon, and a light rain fell gently on her still form. Blood and water soon plastered her hair across her face. Her murderer gazed at her for a moment, then stole away. So....was I right to kill the prologue? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed