Understanding Motivation: Why do some writers complete a novel...and others do not? (yet...)10/12/2015 What motivates some writers to complete a novel? This question has been on my mind for a while. Last week, I did a keynote for another university on motivating and engaging students in higher education (a facet of my day job I won’t go into here). After my talk, someone who knew I was also a novelist said to me, “You know, I used to be a really good writer. All through school, from elementary school through college, everyone thought I would be a novelist. But as an adult, every time I’ve tried to sit down and write a novel, I just can’t do it. How did you do it?” Obviously, this person wasn’t asking me how to write a novel—I’m sure she is well aware of the scores of books that explore the craft of novel writing. But she was asking me a more fundamental question about motivation. “I want to write a book. I have the skills to write a book. I even have a great idea. Other people have written books, some far less skilled and imaginative than me. So why can’t I actually complete something I want to do?”  Why indeed? The day after I delivered that keynote on motivation, I traveled to Raleigh where Bouchercon, the world mystery convention, was getting underway. There, I heard variations of the same question being posed over and over to authors everywhere, in panels, in the book room, over drinks in the bar. How did you do it? And underlying that question, the more desperate ones: Why can’t I do this? What do you know that I don’t? To be clear, I am focusing here on the questions posed to novelists about how they complete a book-length manuscript (or do it more than once), not about how they got their books published (a process which generally transcends self-motivation). I began to pay more attention to how authors replied to this question. Setting the flippant replies aside (“Lots of chocolate!” “Wine!”), a lot of them said things like “Find the kind of writing style that works for you and stick to it.” “Write a set amount of words a day!” “Just keep going!” or most succinctly, “Butt. In. Chair.” Everyone has heard this sincerely intended, tried-and-true advice a million times. The questioner would dutifully nod, but the puzzled look would remain. How do I actually do that? I know what I’m supposed to do, but I don’t actually do it. Why can’t I do what you do? [It's like trying to lose 15 pounds. We all know we're supposed to exercise daily, eat vegetables, avoid sugar, and watch our portions. Or whatever. But it's hard to do.] On the flip side, when I was chatting with some of these writers, I’d ask them what they thought was keeping them from finishing their novels. Here, there were a few variations on a set of themes. Sometimes they focused on time. I have a full time job. I’m taking care of my children, aging parent etc. I can’t find a set time every day to write. I don’t have time to do the research. Or sometimes, they focused on the story itself. I don’t know where to begin. I have writer’s block. The middle is completely confusing. I don’t know how to end my story. My critique group has confused me and I don’t know what to do. Sometimes, they focused on doubt or self-worth or other emotions. I’m just not sure if my story is any good. I don’t know if readers will like it. People are expecting something really great from me, but they’ll know I’m a fraud. I’m not really a good writer. All challenges. All difficult and stressful things. All things that can keep a person from completing a novel. But I’m telling you with some confidence: Every writer who has successfully completed a book-length novel has probably experienced all or most of the same constraints, challenges and boulders in the road. But the difference is, they successfully managed to navigate the obstacles. So the question is: How? Or maybe, Why? [And the answer is not, I assure you, that they are somehow better or more talented than everyone else!] Interestingly, motivation theory can do much to explain why some people successfully complete a given task, and others do not. I’ll say right now that I don’t have a magical novel-completion formula on hand. But I do have a set of questions and some thoughts that might help writers explore their own motivations more fully. These questions include:

Go ahead. Think about these questions. Write down a few thoughts. I’ll wait.

3 Comments

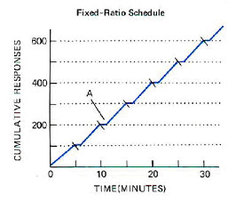

What's he waiting for? What's he waiting for? A few weeks ago, I received my editor's notes for A Death Along the River Fleet. As always, the comments were insightful and thorough, but not particularly hard to address or to think through. And yet I found myself wanting to do anything but sit down and work on them. Everything else was suddenly more immediate, more necessary--organizing a desk drawer, writing a blog post (including this one), and a vast array of other far less important things and activities. Classic procrastination, right?  http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg But why? Why would I procrastinate on a task that I knew I wouldn't mind doing--that I might even enjoy doing? I mean, usually when I procrastinate, its because there's a task looming that I really don't want to do. Like, cleaning the litter box. Pulling weeds in the garden. Other tedious or annoying tasks like that. So why was I putting off a task that I didn't really mind doing? If it's not procrastination, is it simple weariness? Or maybe fatigue? But I didn't really feel exhausted. I mentioned this question to my husband--my alpha reader and in-house cognitive psychologist--because he can offer a psychological explanation for anything that plagues me as a writer (e.g. Me: "Why can't I remember what happens in my books?" Him: "You're not crazy, you're just experiencing proactive interference.") So in this case, he told me that my most recent issue was probably not truly procrastination, but rather something called a "Schedule of Reinforcement." So the schedule of reinforcement goes something like this: Imagine that an adorable little rat with a bright twitching nose is in a box with a lever. That rat is on a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, which just means it will receive a food pellet (reward) after every 100 lever presses. Once the rat begins to press the lever, it will work at a fast steady pace until the food reward is earned (the up slope in the figure below). (So if I'm the rat in this scenario, I've earned my reward--I've sent my book in to my editor and received my edits.) However, once the rat earns the reward, it stops responding for a while (the flat point A in the figure). This is known as either the “post-reinforcement pause” or the “pre-ratio pause.” Essentially, the length of the pause is proportional to the amount of work that was required to get to the reward. The interesting part, he explains, is that, generally, the length of the pause is not due to fatigue. Instead, the rat--or other organism, like a human being--seems to use that time to mentally prepare for the large amount of work to come. He says it’s not fatigue because if you artificially get the organism to begin (e.g., place rat paws on lever so that it depresses), then the organism will go on a “ratio run” and perform the behavior until the next reward is given (even if it just completed a run and had no break). So apparently, this has interesting implications for procrastination with humans. As he explains, research on schedules of reinforcement suggest that the best way for a human to overcome procrastination is to artificially get the human to begin the project. For instance, if a college student has to write a term paper, s/he can trick themselves by saying, “I’m only going to write the first two sentences and then I’ll stop.” Often, once they begin, they go on a “ratio run” and write much more than intended (just like when the rat was forced to depress the lever). So, the takeaway for writers (because this is apparently what happened to me): "When you have to dig back into a project (e.g., edits), it’s probably not fatigue that leads to procrastination. That “procrastination time” is used to mentally gear up for the considerable amount of work to come. Even so, simply starting (e.g., on the easy edits), can lead to a ratio run and solid progress." So a scientific explanation for what we all at heart know is the secret for overcoming procrastination: Get your butt in chair and JUST START....but start with the easiest thing possible. The rest will come. And hey, let me know if you have any other writerly conundrums that you would like a professional psychologist to explain. He can come up with a theory for anything. Just address your query to "Dear Alpha Reader." :-)

I've been running into a funny problem while reflecting on the edits for my second Lucy Campion mystery (From the Charred Remains, out in April 2014!). It's the same problem I encountered when talking to a book group tonight... I'm having some trouble keeping the details of my stories straight. Crazy, right? How can I not know my own stories? I spent YEARS writing them (at least A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.) But still, I have notes and charts and timelines and figures (yes, figures!) detailing subplots, tracking character motivations, etc. And yet, I'm still a bit confused sometimes. How is this possible? So I raised the question of my faulty memory with my chief psychological consultant (literally my resident psychologist, a.k.a my alpha reader). "I wrote the darn thing!" I whined, er, lamented. "How can I not remember all these details? I shouldn't have to re-read my notes to know my own story. Do I just have the worst memory in the world?" And, with a lift of his eyebrow and a stroke to his goatee, my cognitive psychologist replied, "Ah, well let me tell you about a little thing we in the field like to call PROACTIVE INTERFERENCE." And here's what he explained: "I'd imagine it's always harder for the writer to remember the details than it is for a reader. For the reader, there is one reality and it is laid out there on the page. The writer, however, has vividly imagined (and discarded) many realities. These early imaginings compete and interfere with the memories for the most recent version of the story. This proactive interference is a hallmark of human memory and, sadly, it is largely unavoidable. Be thankful that you took good notes in the first place!" (See why I keep my alpha reader in my permanent employ? He helps me rationalize my disorderly thinking with a neat psychological construct!)

But this idea of proactive interference, and this notion of multiple imagined (and discarded) realities, really does resonate with me. I've found that even though I take notes as I write, I don't keep track of the scenes, characters events, etc. that get deleted or shuffled around. So I retain this memory of what I wrote, even though it's no longer in the manuscript, which is why I'm sometimes confused months later. I also wrote another unrelated novel in the interim, which probably doesn't help with my recall of the one currently being edited. Perhaps I could do a better job of documenting the changes I make when I write (although, really, it's not like I EVER get rid of a draft!). But, in a way, I sort of like the idea that underlies this confusion. Maybe it's part of the romantic image of writer as creator: the idea that one being can simultaneously hold multiple realities is strangely compelling. Or maybe its just convenient to pull out the "proactive interference" defense. Dazzle my questioners with the multiple realities angle, and I can sidestep the missing details altogether. But what do you think? Will that fly? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed