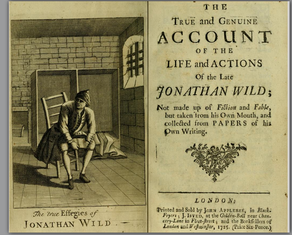

Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!

2 Comments

|

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed