I went on to write two other mysteries, Murder Knocks Twice and The Fate of a Flapper set in 1929 Chicago, featuring Gina Ricci, a cocktail waitress in a Chicago speakeasy. (And some readers have asked me if Gina is Lucy's great-great-great-great-great granddaughter, and I always say, 'sure why not?' When the series is complete maybe I'll work out Gina's genealogy). I honestly thought that my time with Lucy and 17th century London would be over after DARF was published. But then Severn House approached me about writing another Lucy, and continuing the series, and I jumped at this amazing opportunity.

Getting back into Lucy's world was not nearly as difficult as I imagined. Essentially I just had to push my cocktail glasses off the table, stack my Prohibition books back on the shelf, and change my music from flappers fun to classical (I can't quite bring myself to listen to madrigals and baroque music, or drink mead for that matter, to get myself in the right mood). Each of my first four Lucy books all came to me in the form of an image, and The Sign of the Gallows was no exception. I immediately had the image of Lucy standing at a crossroads, because that's where I mentally pictured her (and me) to be. It can't get more "on the head" than that. This image was particularly appealing location for a mystery because in the 17th century a crossroads was still very much viewed as a dangerous and frightening place. Murderers and suicides were often buried at crossroads since they could not be buried in sacred grounds. The idea was that their tortured spirits would not be able to find their way back home and they'd get confused at a crossroads. That also meant, of course, that travelers needed to be wary, when passing through a crossroads, lest they attract one of these unfortunate souls and carry them back home with them.... That image gave way to a plot...Lucy discovers a dead man hanging from a gallows at the crossroads, drawing her into a puzzling mystery. The image of Lucy at the crossroads also informed Lucy's lot in life, and I wrote much of the novel with the idea that Lucy would be on a definite path by the story's close. However, ironically, just as I was writing the last chapter, I was asked by Severn House to write a sixth Lucy Campion mystery-- which meant I had to rethink Lucy's crossroads conundrum. A fun challenge to have! It's been so fun to jump back into Lucy's world. As I was writing, I did have this weird sense my characters had been waiting for me. A little like Pirandello's "Six Characters in Search of an Author," only the 17th century version. (Although that's a little disturbing, if you think about it too much). It's been really gratifying to be able to move Lucy's story forward, and to tell a story I never thought would be told.

8 Comments

Dorothy Sayers Dorothy Sayers Recently* I came across the Detective’s Oath, written by Dorothy Sayers and first administered by G.K. Chesterton, as part of the initiation ceremony for the British Detective Club. The club, created in 1930, included the likes of Sayers, Agatha Christie, and a slew of other Golden Age mystery writers. The oath was this: “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?” While I think we’ve all seen authors—well-known ones at that—break these principles regularly (after all, why can’t a ghost solve a crime? Or for that matter, a cat?), there was something to these expectations that made sense. A reader should be able to work out whodunit, at least after the fact, to be fair.  But when I first read the oath, I had to laugh. I have situated my mysteries in early modern England, a time when divine revelation, providence, acts of God (or the Devil, for that matter) often served as the explanation for most mishaps and misfortune. It would have been so easy—and realistic—to have my sleuth solve crimes in that fashion. After all, there are many incidences of a community “solving” a murder when a corpse’s finger pointed to its murderer. Or when the corpse’s eyes would open and stare in the direction of the murderer’s house. There are even examples of a corpse bleeding from the nose or ears, indicating that the murderer was in the vicinity. Sometimes, logic and reason and evidence would prevail and sometimes…they did not. There are many examples of superstitions, hearsay, and feelings making their way into court testimony, especially in ecclesiastical courts.  Certainly in A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, when a young woman is found dazed and confused with blood on her clothes, there is immediate suspicion that she might be bewitched. But I wanted Lucy Campion, my chambermaid turned printer's apprentice, to be someone who was resourceful and intelligent, despite having little formal education. But it wasn’t just about creating a character who would use her wits and evidence to solve crimes; I wanted her to question how the community identified murderers in the first place. I also wanted Lucy to be someone who rejects the notion of providence as a means to explain murder. I wanted her to dismiss the idea that divine revelation could be a reliable way to identify a murderer—even if that meant challenging the expectations of her community. I’d like to think that Lucy would approve of the Detective’s Oath. This post was first published on the Bloody Good Read.

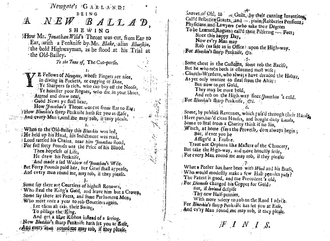

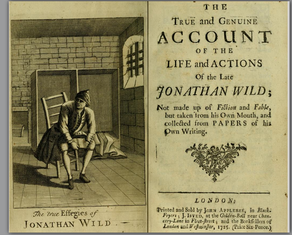

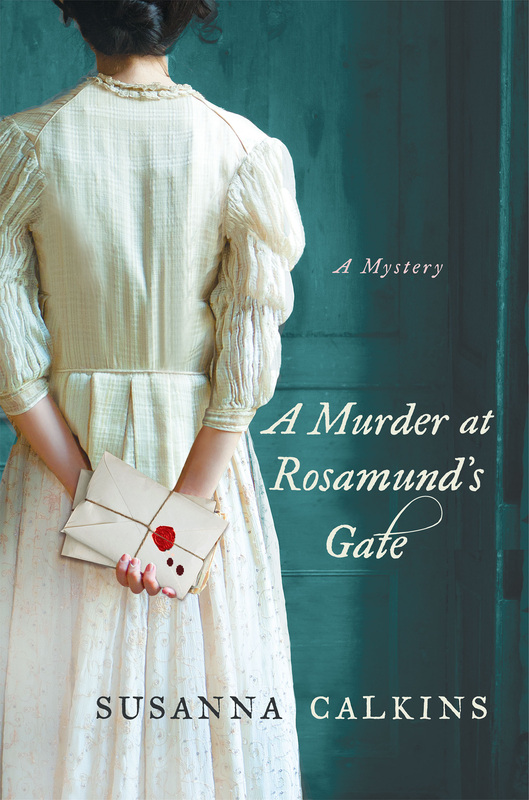

1677 Wing / 1528:11 1677 Wing / 1528:11 "Where do you get your ideas?" I don't know what it is about this question that drives some writers bonkers, but it's one we all get at book talks and literary events. In response, some authors take the humorous approach ("In Aisle Twelve"), and others try to ignore the question outright ("Next!") Some will roll their eyes and joke about banning the question before offering their response. Personally, I never really understood the reluctance because I love answering this question. I find it so much fun to tell people about the murder ballads that inspired my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. I wonder sometimes whether the real question is not "Where did you get your ideas?" but really, "Where did you get your questions?" Because at the heart of all my books are questions I'm trying to answer, and I suspect this is the same for many authors, perhaps particularly those who write crime fiction. Indeed, I get a lot of my ideas--and questions-- simply by poking around the Early English Books Online. For example, I've been thinking a lot about poisons lately--because, you know, writer--and I came across this gem. The story from 1677 pretty much writes itself! "Horrid News from St. Martins: Or, Unheard of Murder and Poyson. Being a true relation how a girl not full Sixteen years of age murdered her own mother at one time, and a servant-maid at another time with ratsbane. As also, how she very lately gave poyson to two gentlewomen that since met her Mother's Death kept and maintained her. Upon which being apprehended, she has confessed the former villanies, and was on Tuesday last the 19th of this instant June, committed to Prison, where she now remain."  What a great story, right? A sixteen-year old serial killer poisoning the women closest to her? What's up with that? And with ratsbane? That's not an easy way to go either... So of course I have lots of questions... This story may not make it into one of my novels, or who knows? It could be the crux of the whole tale. But the point is, ideas don't come fully formed, they come in bits and pieces. The important thing is what we do with those ideas--the questions we ask when we ponder different ideas. It's not just whodunnit--its all the other questions that drive the story forward. I think, ultimately, that the idea is not a story until the writer learns to get beyond the "What happened?" and begins to ask "Why?" But what do you think?  For many of us who work on college campuses, the specter of violence often looms. For instructors, there is an additional vulnerability, a sense of being studied and examined as intently as if they were the subjects of the course. In my day job, instructors frequently speak of feeling naked and exposed when they teach. Indeed, the public scrutiny can be tough for instructors. Even those who can bear it may still acknowledge a somewhat alarming truth: Students may know all kinds of things about us--often well before we know a single thing about them. So looking out at that sea of student faces, instructors may find themselves asking--who are these students, really? What are they thinking? What are they hiding? These are the kinds of questions that Lori Rader-Day explores in her stunning debut novel, The Black Hour (Seventh Street Books). In this compelling work of fiction, a sociology professor seeks to understand why a student she didn't even know tried to kill her. I invited Lori to chat about her novel on my blog. [Full disclosure: Lori and I work at the same university, although we actually met at Printer's Row in Chicago last year.]  The Talented Lori Rader-Day The Talented Lori Rader-Day Could you tell us about what inspired The Black Hour? I know that you work at a university—what role did that play in your inspiration? You don’t have to work at a university to worry about the violence happening on campuses across the nation, but because I do work at a university, it’s something I think about. But The Black Hour is more about the aftermath than the violence itself. The idea was: what would a first day back on campus be like for someone who survived an act of violence? Since the perpetrator was no mystery, the question had to be why. When I started writing, I didn’t know why, either. I had to keep writing until I knew why. The Black Hour is told through the alternating perspective of two individuals—the sociology professor who was the victim of the shooter, and a graduate student serving as her Teaching Assistant (TA). What contributed to your decision to tell the story using two voices? What were the challenges and the benefits of this technique? Originally I started the book from Amelia’s perspective. In the first few chapters, she met a new graduate student who was interested in her work studying violence. About 50 pages into writing the book, I realized I had a problem. Amelia was newly injured. How was she going to go scampering all over campus looking into her own attack? It turned out that the student, Nathaniel, had more to say. And then took over half the book. The challenge was in keeping the two first-person narrators separate so that a reader would know who was talking at all times, but the opportunities were greater. I had a lot of fun playing them against each other, and forcing them to share the story gave the novel its structure and pace.  Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  My book started years ago, when I was a graduate student, pouring over 17th century murder ballads. The ballads served as musical 'true accounts' of murderers who wrote letters to their victims, urging them to rendezvous in dark deserted fields. I knew I had to write about these monsters. I drank lots of coffee.  I spent years writing this first book, scene by scene, in little half hour bursts, at coffee shops, on the train, when the kids were sleeping, until one day--in 2010-- I finished. Even my husband--alpha reader extraordinaire--did not know much about the story. "It's set in the seventeenth century," I'd mumble. "A servant gets killed. Another servant tries to figure it out. Stuff like that." But eventually, I asked him and a few other trusted friends to read the book. I revised again, queried, queried, queried, while writing an entirely different book in the interim. In 2011, I got my wonderful agent who quickly connected me to my equally wonderful editor at Minotaur. My journey was no longer an imaginary jaunt; the path to publication was suddenly very real.  In 2012, more changes happened. The title of my book got changed. My publication date got pushed back. My beautiful cover was revealed. Multiple revisions happened. Copy edits made me crazy, but I learned a lot in the process. I had my first public appearance as a novelist ("2 minutes at Bouchercon"). At some point, I received my ARCs. 2013. Months still passed. My book began to be publicized. I reached the 100 Day mark. Another few months passed. My book started to be reviewed. My hardback copy came in the mail. And now...Be still my heart... MY BOOK IS FINALLY HERE!!!!

Thanks to all my colleagues, friends and family--especially my husband--who made this possible!!!!  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.  Intrigued? Then check out my most recent post on A Bloody Good Read: Where Writers and Readers of Historical Thrillers Talk Shop  Do you prefer a puzzle at the outset... What kind of mystery do you prefer--the kind that presents a puzzle from the outset, or one that reveals the puzzle during the investigation? Let me know! Check out my post on this topic over at A Bloody Good Read!  the murder may have happened here I had the opportunity the other day to contribute to a great blog, A Bloody Good Read: Where writers and readers of historical thrillers talk shop. There, I talked a little about a long ago murder and how a writer can fill in where historians fear to tread. Inspiration can be found in many places, I guess!  If you have a few minutes, check out the great entries by my colleagues: Nancy Bilyeau, author of The Crown (Touchstone, 2012) (she's also worked for all kinds of publications like Rolling Stone, In Style magazine, and Entertainment Weekly)...  ...and Sam Thomas, an early modern historian specializing in midwifery. Sam's first novel, A Midwife's Tale (Minotaur/St. Martin's) is due out in early 2013. |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed