Reconstruction of Lincoln's Inn Fields Reconstruction of Lincoln's Inn Fields While I work on my copy edits of The Masque of a Murderer, I thought I'd post something about Lincoln's Inn Fields Theater, which plays into my third novel. Lincoln's Inn Fields Theater interested me because it was one of the playhouses that King Charles II built in 1661 after he was restored to the throne. Ironically, it was not originally intended to be a theater, but a tennis court. (You can see the long rows of box seats on either side where an audience would have watched a match). The Lisle Court only became a theater in 1662, before being temporarily closed during the plague in 1665. [There may also have been a murder that occurred there, but somehow that tale has only recently resurfaced :-) ] In doing my research, I came across the work of Steve Bouler, a theater professional and academic, as well as being an extremely talented designer of virtually reconstructed theatrical playhouses. It's hard to express how immensely helpful these reconstructions are to a researcher. Since so many of these Renaissance and Restoration playhouses are now gone, we must rely on extant sketches that can be difficult to track down,and even more difficult to interpret. I know I spend a lot of time looking over faded sketches with teeny print, trying to figure out how everything fits together. But when I came across these reconstructions, I gained a far better sense of how plays would have been staged (and received). You'll understand when you check out Bouler's amazing panoramic reconstructions! Check it out! Image: http://historicalplayhouses.com/Lincoln_s_Inn_Fields.html

1 Comment

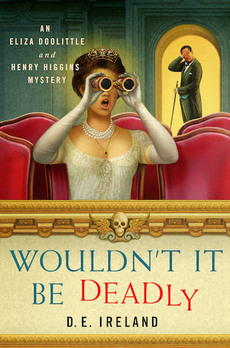

A while back someone gave me a book on writing, which contained a number of random quotes by writers. As a historian, I am sometimes frustrated when presented with quotes that have been detached from their original context and passed off as inspirational or profound. So as I was flipping through the book, I came across this one that made me sit up and take notice: "The author must keep his mouth shut when his work starts to speak." -Friedrich Nietzsche  So without knowing anything about Nietzsche, I might interpret this as a humble phrase. Let your work speak for itself. Perhaps, it is a warning. You must let others critique your work as they will, once it is out in the world. Do not answer your critics. Or maybe it is just a reminder to writers. Do not edit or self-censor as you write, but allow your work to emerge in the world in its most full and beautiful form. I assume because the quote was included in this writing book, and is oft-repeated (again, with no context) on many writing sites, that this admonition is seen as a virtue. Do words have meaning of themselves? Do they live, and change with the times? Or do they need to be ever-framed by the context with which they were first uttered? Consider the source of this quote. Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche was a nineteenth-century German philosopher, philologist and poet, among other things. Such as being a megalomaniac. And a syphilis-riddled man who spoke frequently of his own genius. A man whose work inspired both Nazis and Fascists alike. Altogether, an intriguing--if tortured--soul. So what did he mean when he said this? As I indicated, it's very difficult to identify the source of this quote, so for all I know it is completely inaccurate and has just been repeated ad nauseam. Some digging for the past hour (which is about all the time I have to devote to this quest) has yielded little more context, except that I think, but can not be sure, that the quote appeared in the second edition of Nietzsche's first published book The Birth of Tragedy, in a new section called "Attempt at a Self-Criticism" (1888). Rather than being a true self-criticism, however, the statement is widely viewed by scholars as a means for Nietzsche to clarify his earlier views, and to impose his later thinking onto his earlier work. Such a revision could be construed as more arrogant than humble ("See how brilliant I was, even when I was a young man?") This additional context, to my mind, sheds a different interpretation on the quote. Should we just make sense of words ourselves? Or does the larger context matter? While there's a pleasing democracy about the idea that we can all interpret words for ourselves, for my part, I think, understanding the larger context almost always offers a more full and interpretation of words. But what do you think? [P.S. I also find it amusing how often the above quote by Nietzsche is used by authors, when it turns out that he actually did write "Rules for Writers" that are NEVER EVER quoted. Such as this gem: "Be careful with periods! Only those people who also have long duration of breath while speaking are entitled to periods. With most people, the period is a matter of affectation." Rich stuff indeed!] Image: Lou Andreas-Salomé, Paul Rée and Friedrich Nietzsche (1882) Given that My Fair Lady is one of my favorite musicals, I was quite intrigued when I learned that D.E. Ireland had transformed the unlikely uncouple--the curmudgeonly linguistics professor Henry Higgins and the charming but inarticulate Covent Garden flower-girl--into a crime-solving duo. Loverly! I am thrilled that the two authors who comprise D.E. Ireland were able to waltz their way over to my blog today, and answer some questions about their debut novel and the writing process.  From the official blurb: Following her successful appearance at an Embassy Ball—where Eliza Doolittle won Professor Henry Higgins’ bet that he could pass off a Cockney flower girl as a duchess—Eliza becomes an assistant to his chief rival Emil Nepommuck. After Nepommuck publicly takes credit for transforming Eliza into a lady, an enraged Higgins submits proof to a London newspaper that Nepommuck is a fraud. When Nepommuck is found with a dagger in his back, Henry Higgins becomes Scotland Yard’s prime suspect...  D.E. Ireland researching high tea D.E. Ireland researching high tea SC: I know that the two of you became friends when you were undergraduates, but how did you become “D.E. Ireland?” Can you tell us a little bit about how you decided on the name? Does it mean something? DEI: We are longtime friends and critique partners and have been looking for an idea to collaborate on for years. And voila, while singing to the My Fair Lady soundtrack on her way to visit Sharon a few years back, Meg stumbled on putting Eliza and Higgins together as amateur sleuths. We plotted, outlined, then wrote the first book in the series. Since we're both published authors under our own names, we needed to choose a pseudonym. We finally agreed upon ‘Ireland’ in honor of George Bernard Shaw who was born in Dublin. And ‘D.E.’ is Eliza Doolittle backwards! SC: Your mystery features the unlikely yet beloved couple from stage and screen, Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins, from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (later adapted as My Fair Lady.) What was it about these characters—a guttersnipe from the dredges of London, and a professor of linguistics—that appealed to you as amateur crime-solvers? DEI: We are both huge fans of the play and the movies. Since Shaw's Pygmalion is in the public domain, we used his play and the delightful banter between Eliza and Higgins as the models for our own series' characters. However we had to flesh out their backgrounds along with that of the other characters such as Pickering, Mrs. Pearce, Mrs. Higgins and the Eynsford Hill family. In the play, Eliza worked hard to win Higgins's bet, yet she hadn't truly earned – and kept! – his respect until our series. We want to keep alive the witty exchanges these two whip at each other, and continue to expand on their friendship as they turn their collective talents to sleuthing. That should be great fun. SC: The book offers a great deal of detail about life in Edwardian London (1913). How did you conduct your research into this era? What was the most interesting or surprising thing you learned while conducting your research? DEI: We are both research hounds; Sharon wrote several historical romances set in the Old West and Victorian England, while Meg has written American western mysteries. Sharon was also a college history instructor so the opportunity to research Edwardian England seemed like great fun. We eagerly started digging into the era immediately following the death of King Edward VII. We love the two PBS series Downton Abbey and Mr. Selfridge, and both shows serve as inspiration. But we rely heavily on our "Edwardian Bible" which we have compiled that includes London shops, streets, parks, neighborhoods, food, social behavior, etc. And of course, we always refer to Shaw's Pygmalion, along with his appendices and notes of the play which include descriptions of Higgins' phonetics lab and his mother's Chelsea flat. Book 2 required that we expand our research to include horse racing, Ascot, the Henley Regatta, along with the suffragette movement. The most interesting or surprising thing? Hmm. Since electricity, autos, the telephone, and the cinema had shown up by the 1900s, perhaps it was our realization at how similar life was then to our times now -- except for fashion and manners of course. SC: Do you foresee Henry Higgins developing over time? Will he be out petitioning for votes for women in future novels? DEI: Oh, we think Higgins is the one who will be clinging to his fencepost, kicking and screaming for the old days. Eliza is the changeling of the pair and will tug and pull him into the 20th century! Oh, yes! It's exactly what you think. Read on! Naturally, the subtitle says it all... “Giving An Account of an Old Miserable Woman, who lately kept a blind ale-house, in St. Tooley-Streat, near the Burrough of Southwark; who was so wretchedly covetous, as to deny her self the common benefits of life, as to meat and cloaths; leaving, at her death, about fifteen hundred pounds, to her cat, using to say often, when the cat mow’d: “Peace Puss, peace: The poem that ensues is a bit silly but sort of endearing as well. (And I have to say, it was nice to see a relationship between a woman and her cat that was not wrapped in accusations of witchcraft, bestiality or other fantastical conjectures.) As the story goes, for years, this "mean" woman did not spend her money, preferring to keep her alehouse earnings to herself. Finally, when no one had seen her for a while, one of her neighbors went in to check on her: “Upstairs he went, and in the bed, He found the Rich Old Woman dead: And, looking in a truk just by, Near Eighteen Hundred Pounds did lie. No sooner he had found the hoard, But he divulg’d it all abroad: Then shockt the neighbours, to behold, The Treasur’d bags of coyned gold. Thus did she cheat the battle such, They thought her poor; for she was rich: Her belly saved it for her CAT, But Puss must shew the will for that." Unfortunately, there's no word on what the cat did with her legacy, but hopefully she was able to get a nice mouse cobbler from time to time.

Not crazy though, right? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed