|

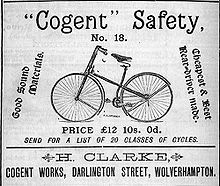

Writers are frequently enjoined to "write what they know," and my guest blogger today has certainly taken that message to heart. Edith Maxwell, author of the the forthcoming historical mystery, Delivering the Truth, features a Quaker midwife in 19th century New England. Edith is a Quaker, has taught childbirth classes, and lives in New England. So I guess she knows what she's talking about!!!  From the official blurb: For Quaker midwife Rose Carroll, life in Amesbury, Massachusetts, provides equal measures of joy and tribulation. She attends to the needs of mothers and newborns even as she mourns the recent death of her sister. Likewise, Rose enjoys the giddy feelings that come from being courted by a handsome doctor, but a suspicious fire and two murders leave her fearing for the well-being of her loved ones. Driven by her desire for safety and justice, Rose Carroll begins asking questions related to the crimes. Consulting with her friends and neighbors―including the famous Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier―Rose draws on her strengths as a counselor and problem solver in trying to bring the perpetrators to light.  Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used In my Quaker Midwife Mysteries, Rose Carroll is a midwife helping pregnant women give birth in the safest way possible - in the 1888 New England mill town of Amesbury. She’s twenty-four, as yet unmarried, and a Quaker. Rose is an independent businesswoman, unconventional both for going about her business on her bicycle and for being a member of the Society of Friends. Quakers have long been known for being unconventional, though, and New England Friends of the era even more so. Rose’s mother works tirelessly for women’s suffrage. Rose’s friend and mentor, the real John Greenleaf Whittier, was an outspoken abolitionist and supported equality among his fellow humans. Rose addresses everyone by their first name regardless of social class or occupation, and speaks using “thee” and “thy” as Quakers did, so she’s used to traveling outside certain norms. She’s also known for her honesty and clean living. Her clients trust her. Although there was a New England Female Medical College, which was a training school for midwives, Rose took the traditional route and apprenticed with Orpha Perkins to learn her trade. When the elderly Orpha retires, Rose takes over her business. The late 1880s is a fascinating period to write about because so much was changing, including the practice of midwifery and medicine. The germ theory of infection was known, so Rose is careful to wash her hands and keep the birthing chamber clean. A new hospital had been built across the river in the bustling seaport town of Newburyport only a few years earlier. Cesarean sections were done, but it was still a very risky procedure. And male doctors were starting to do deliveries, practicing obstetrics. I read that this practice increased in part because women working in factories were living away from their female relatives who would normally support them through the birth and postpartum period. The husband of one of Rose’s clients insists that his baby be delivered by a male doctor, but most of Rose’s pregnant clients much prefer having a woman attend them. I also read an account of a Massachusetts midwife being sued in 1905 for practicing medicine without a license. I haven’t heard of such accusations twenty years earlier, however. Of course, being a midwife makes Rose a perfect protagonist. She can go places no male police officer can – women’s bed chambers – and hears secrets the detective isn’t privy to, both during labor and at client visits. I know in earlier times midwives had a obligation to extract information from unwed mothers about the father of the baby and report him to the authorities, but I haven’t been able to unearth whether that practice still stood at the end of the nineteenth century. (See Sam Thomas' excellent post on the role of midwives in 17th century England, for example. -SC)  Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission I’m delighted to follow Rose around the streets of my town where many of the buildings of the late 1880s still stand, including the Friends Meetinghouse where she and Whittier worship, and write down her adventures.  Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries (Midnight Ink) and the Local Foods Mysteries, the Country Store Mysteries (as Maddie Day), and the Lauren Rousseau Mysteries (as Tace Baker), as well as award-winning short crime fiction. Her short story, “A Questionable Death,” is nominated for a 2016 Agatha Award for Best Short Story. The tale features the 1888 setting and characters from her Quaker Midwife Mysteries series, which debuts with Delivering the Truth on April 8, 2016. Maxwell is Vice-President of Sisters in Crime New England and Clerk of Amesbury Friends Meeting. She lives north of Boston with her beau and three cats, and blogs with the other Wicked Cozy Authors. You can find her on Facebook, @edithmaxwell, on Pinterest, and at her web site, edithmaxwell.com. Want to know more about the original Quakers from 17th century England? Check out my discussion of the political activities and writing of Quaker women. Or this post on their last dying speeches.

0 Comments

In my third historical mystery, The Masque of a Murderer, Lucy Campion, printer's apprentice, has been asked to record the last words of a dying Quaker. He had been run over by a cart and horse the day before, and was slowly dying from his extensive injuries. A number of people have gathered by his bedside, listening to his final rambling words, testifying to his journey from sinner to one who has found the "Inner Light." And before the man finally succumbs, he regains a moment of lucidity and manages to tell Lucy that he had, in fact, been pushed in front of the horse and his death was no accident. Moreover, he believed that his murderer had to be one of his closer acquaintances, perhaps even a fellow Quaker. The premise came from a tradition that was common in early modern England of recording the "last dying speeches" of different types of individuals. Such speeches were common for criminals about to be executed, for example, and which would be distributed at the gallows for eager spectators. [In From the Charred Remains, I have Lucy selling some of these at the public hanging of a criminal]. Often written by clergymen, such chapbooks or pamphlets were usually both pious and didadic in tone. As historian J.A. Sharpe has put forth: “The gallows literature illustrates the way in which the civil and religious authorities designed the execution spectacle to articulate a particular set of values, inculcate a certain behavioral model and bolster a social order perceived as threatened. Only a small number of people might witness an execution, but the pamphlet account was designed to reach a wider audience.”*  Wing W2039 Wing W2039 Indeed, there was a similar quality to other types of sinner's journeys that were published as chapbooks or pamphlets. Quakers, who produced hundreds of tracts in the 17th century, frequently recorded the last words of Friends whom they wished to hold up as a means to extol a certain value or set of virtues for others. For example, when I was writing my dissertation on 17th century Quaker women, I came across a poignant tract--The Work of God in a Dying Maid (1677)**--written by one of the more prominent Quaker leaders, Joan Whitrowe, detailing the death of her daughter, fifteen-year old Susannah. The 48-page tract tells the story, not just of Susannah's death, but of the young girl's early struggles with temptation. The testimonies, written by Joan and other local leaders, demonstrates how Quaker children and youth were supposed to behave, and why they should listen to the advice of their parents and other elders. Indeed, Joan dedicates the work as a warning to those wayward souls, "who are in the same condition [Susannah] was in before her sickness." But the back story that emerges throughout the pious testimonies is quite compelling. As Susannah lay dying in her Middlesex home in 1677, neighbors whispered that the cause of her "distemper" was a recently thwarted romance. Questioned by her parents, the young Quaker admitted that a certain man was "very urgent with [her] upon the account of Marriage" and since her father had been a "little harsh" to her she thought she would set herself "at liberty." But upon reconsideration she allegedly told her suitor, "I would do nothing without my Father and Mother's advice." She assured her mother, "before I fell sick this last time, I did desire never to see him more." [Here are some of the lessons about virtue and obeying one's parents--and the consequences of not doing so.] Feverish, restless, and in pain, the young Quaker reportedly clamored for God's swift judgment, mercy, and an end to her suffering. For six days her mother and father and various friends maintained an anxious vigil at her bedside, praying and recording Susannah's final excited visions and earnest penitent speeches to God. She chastised herself for her vanity, "How often have I adorned myself as fine in their [her female acquaintances] fashions as I could make me?" She berated herself for bringing shame to her family and lamented speaking out against her mother’s sect: "Oh! How have I been against a woman's speaking in a [Quaker] meeting?" What we can not know of course, is how much of this Susannah actually said, and how much was expanded upon in the written narrative to make the larger point about godliness. But it gives a sense of the way that people's final words were recorded, and it offers a fascinating backdrop for a murder mystery... *J. A. Sharpe, "Last Dying Speeches": Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England. Past & Present No. 107 (May, 1985), pp. 144-167. quote on p.148.

Joan Whitrowe, The Work of God in a Dying Maid: Being a Short Account of the Dealings of the Lord with one Susannah Whitrowe (n.p., 1677), 16.  I can't tell you how excited I am to see the cover of my first novel!!! A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. I think the artists at Minotaur captured the essence of my story beautifully. The opening (and closing) images of my novel are of Lucy standing at a door. There are some other clues about the story tucked away here, but you'll have to read the book to discover them for yourselves!!!  Esther Biddle, Quaker, 1660 This weekend I had the fun of seeing my first guest blog "Prophecy and Polemic— The Earliest Quaker Women" posted on the English Historical Fiction Authors website. There, I discuss why Quaker women were so political and how they differed in one particular way from most other women at the time--even members of other non-conformist sects (such as the Diggers, the Ranters, the Levelers etc). And oh! how they expressed themselves... Dressing in sack-cloth "Running naked as a sign" Refusing to bow to authority But that wasn't all... Quaker women were different because they wrote. And they wrote. And they wrote. And they wrote. In fact, as a group, Quaker women wrote 220 tracts before 1700, more than any other women. Petitions, broad-sides, chapbooks--all carrying admonitions to King, Parliament and clergy to recognize sinful acts, accounts of injustices and cruelties to their members, and pleas to release their religious brethren from prisons and authorize non-conformist worship in England, and the American colonies. I've always respected the bravery and creativity shown by the earliest Quakers, in their attempt to get their message heard. I've often thought how hard that must have been for them to write these open pieces. They were not just challenging Parliament, Magistrates, Churchmen and the King: they were challenging convention and the very heart of patriarchy, often risking public ridicule, shaming, abuses and imprisonment. Taking the mantles of Old Testament prophets, mid-seventeenth century Quaker women wrote openly about the social wrongs they perceived around them, especially those caused by the (imagined and real) abuses of men in power. In the soul-examining spirit of the time, Quaker women--like their male counterparts--also wrote publicly about their own struggles to find the "Inner Light" and to give up earthly fripperies. (Poor Susannah Whitrowe--she really wanted to cling to her ribbons, but knew she wasn't supposed to) They wrote about death and heartbreak, joy and promise. (This is not too suggest that they did not use their expressions of suffering to advance their cause--both politically and religiously--but there is an honesty to their expression that is admirable). At a time when women who wrote were disparaged as "petticoat authors," early Quaker women persevered to make their voices known. Just as they "ran naked as a sign" to convey their discontent to religious and secular authorities, they wrote nakedly too. They laid their emotions and concerns bare, for public consumption, expressing themselves in ways that were both daunting and inspiring. As I writer, I certainly struggle to lay my words bare on the page. Those little editorial voices are hard to muffle! I'm hoping, with time, to find my most authentic voice. How about you? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed