Among the many things I never expected when I began to publish my historical mysteries is the steady stream of questions I get from readers. I really enjoy getting these questions, but sometimes I'm a little perplexed. The "easy" questions focus on interesting historical details, like how people kept time in the 17th century or what the revolving signet ring described in From the Charred Remains actually looked like. Sometimes they focus on larger questions, such as the gendered nature of the printing industry, the so-called "miracle" of the Great Fire, and the like. Sometimes, I just answer these history-related questions in a quick email, but I will probably start answering them in more detail on this blog. However, what's interesting to me is the number of questions that I'm starting to get about the decision-making processes that accompany the writing of a novel, especially historical fiction. "How do I decide on a time period/setting for my novel?" "How do I begin my research?" "How much research do I need to do?" "How much historical detail is enough?" "Do I need footnotes?" I hate to say it, but all of these questions can be answered in a single phrase. It depends. I know, I know. That's not very helpful. Since I've written at length in Writers Digest about seven tips for writing historical fiction,"Balancing accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction," I won't go into detail about those writing strategies here. And really, I don't have any particular insights about how to select an interesting time period. Choose a time period that fascinates you, intrigues you, keeps you enthralled. Keep in mind: this time period had better hold your attention, since writing a novel takes a very long time indeed! If you become bored with the time period, I have no doubt it will show in your writing, and your reader will become bored too. Truly, to answer such questions: "Have I done enough research?" "Have I offered enough historical detail?" "Do I need footnotes?" it really does depend on who your intended audience is, the kind of book you are writing, and the conventions of the genre. To answer these questions, there's a bigger question that you really need to ask yourself first: Am I actually writing historical fiction? This seems like a simple question, but I've been quite surprised when readers and writers ask me about the difference between history and historical fiction. It's clear to me now that there is a spectrum of categories, associated with the writing of history. None is "better" than another--each has a different purpose. I thought I would lay out how I conceptualize the difference in these categories: (1) Scholarly historical writing: This type of non-fiction writing is usually conducted by scholars and academics, produced in institutions of higher learning, museums and libraries, with highly specialized audiences and very small print runs with academic presses. Historical narratives and interpretations are framed by theory, historiography, with a strict adherence to evidence found in primary and secondary sources. Footnotes are crucial for credibility. Usually peer reviewed by other scholars/specialists before proceeding to publication. (2)Popular historical writing: This non-fiction writing may be very similar in scholarship to academic writing, but it may be more sensational in nature; it may be mass produced by commercial presses and readily found in bookstores; less emphasis may be placed on historiography and theory, but these features may still be present. Standards of evidence may be less strict. May not be peer reviewed, or only reviewed by editors. Generally, the writing seems more accessible and is intended for a lay audience. Footnotes are present, but are used more to explain ideas than to provide citations for every piece of evidence (again, this varies by publisher). (3) Fictionalized History: This is a tricky category to explain, because I think it is usually lumped together with historical fiction. I think this occurs when a writer takes a well-known historical narrative and adds to this narrative with made-up conversations and interactions between real historical figures. There is a great deal more supposition and creative license in constructing this type of narrative. Evidence may be selectively used to frame the overall story. Footnotes may be expected by readers. I think it is safe to say that this category can be called "Based on a True Story." (4) Historical fiction: While this varies, I would say that in this category, the historical narrative usually forms a backdrop to the story, with characters interacting with authentic details. Background theory and research will inform the best writing in this category, but will be implicit, not explicit. Historical fiction is not usually produced by academic presses, and undergoes editorial, not peer, review prior to publication. Much of the main plot may be fictionalized, even if there are real characters and true historic events being described. So in my case, the 17th century plague and the Great Fire of London form the backdrop of my stories, and my completely fictional characters sell murder ballads, spend time in Newgate prison, and scrub chamberpots. I do not have footnotes (ack! ack! not in a novel! Convention right now, at least in traditional publishing, is to eschew footnotes), but I do have a lengthy historical note in each book to explain historical points more or to indicate where I stretched the facts slightly to enhance the storytelling. I avoid information dumps, and try to get my characters to engage with the historical details. I'm telling a story, not writing a textbook. In any one of the above-mentioned categories, however, writers may be seeking to shed light on a little known historical event or figure, to expose larger truths, to offer new explanations and interpretations about a historical event or idea, or simply to provoke curiosity about a bygone era. One category is not BETTER than another; there are different purposes for each (and there are examples of good and poor writing in every category.) Ultimately, the level of historical detail and the length of the book will depend upon your intended audience (children, adults, scholars, history enthusiasts etc), the opinion of your editor and publisher, the conventions of your genre, and most importantly, the story you are trying to tell. But what do you think? Do these categories make sense?

4 Comments

Guest Post in Writer's Digest: Balancing authenticity and accuracy while writing historical fiction9/8/2013  My post in WD appeared Sept 6, 2013 My post in WD appeared Sept 6, 2013 A few years ago, when I was first trying to figure out how to get my debut novel A Murder at Rosamund's Gate published, I came across Writer's Digest. Full of advice for the fledgling writer and published author alike, Writer's Digest gave me some great insights into what I needed to do to polish my manuscript and write a compelling cover letter. (I mean, tell me it's not important to know "How to see your work through an agent or publisher's eyes?" or, "Knowing when to stop: Expectations for a satisfying ending.") So I really appreciated the opportunity to write a guest post, "How to write historical fiction: 7 tips on accuracy and authenticity" for Writer's Digest. In this post, I talk about the tensions I've experienced as a historian-turned-novelist, while writing historical fiction. I also try to offer a few strategies that have worked for me in reconciling these tensions. Check it out! And while you're there, try out the daily writing prompt! Although I have to giggle, because today the prompt is: "You are a local news reporter for a failing network. Your boss tells you to ramp up the news by getting “creative” and constructing your own stories. What’s the first fake news story you create and broadcast on air?" Fake News! Totally fun! Accuracy Shmackeracy! If you do take up the challenge, will you post it here too? I'd love to see it!  Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 I had to laugh when I came across this tract by John Raymond, 17th century author of Folly in Print, or A Book of Rymes (1667). Right away, on the first page, he lets the readers know it really isn't his fault if you don't like his book: "Whoever buyes this Book will say, Next, Raymond then explains to his readers that if they believe what the bookseller says (or sings, as was often the case), it's their own fault if they find they don't like the book after all. "... in Books, where for money or exchange, we take our choice, and in our own Election please our selves; Can you imagine if authors could still add this type of caveat emptor today? Madness! But I'm sure there are many authors today--especially those stung by hurtful reviews--who might wish they could say something like this to their readers: I doe not promise for my Book nor say 'tis good, but here's variety and each man (of his own pallat) is the certain judge: You might like my book, you might not. To each her own!

But what do you think? Have you ever felt deceived about a book?  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.  Mary Amelia Ingalls (1865-1928) Until yesterday, if you had asked me what I knew about scarlet fever, I would have been able to tell you two things: A lot of people seemed to have contracted it in the nineteenth century, and in severe cases, a person could die, or at least go blind. My evidence? Well, Laura Ingalls Wilder of "Little House" fame attributed her sister Mary's blindness to scarlet fever. I, for sure, took this diagnosis at face value. Why wouldn't I? However, as it turns out, Mary probably suffered from viral meningoencephalitis. In a recent Pediatrics article, Dr. Beth Tarini and some colleagues reported their reassessment of Mary's condition, having spent years pouring over Laura's letters and other documents which alluded to Mary's symptoms. Even though Mary had indeed contracted the disease as a child--in both the TV show and the book, we were infomed that "her eyes had been weakened as a child"--other symptoms were more telling. She went blind as a teenager, in 1879. Half her face had apparently been paralyzed, along with her eye muscles. Most telling of all, Laura later refers to Mary's "spinal sickness" in a letter to her daughter Rose. In 1881, Mary went to the Iowa Braille and Sight Saving School.  Helen Keller, 1880-1968 Interestingly, a thousand miles away in Alabama, Helen Keller--an infant-- had also just contracted a disease that caused her to lose her sight and vision. Like Mary Ingalls, her condition was also attributed to scarlet fever. Physicians now suspect, however, meningitis was the more likely culprit. Was the assumption of scarlet fever simply a misdiagnosis? In the case of Helen Keller, this is quite possible. In the case of Mary, no. Dr. Tarini's team concluded that the family was aware of Mary's true disease, but that Laura had deliberately obscured the nature of her sister's condition when she discussed it in her books. Why would Laura have changed her sister's disease? Dr. Tarini conjectured that scarlet fever, being a common malady, would have been more relatable to the author's audience. There's something to that hypothesis, for sure. However, at the end of the nineteenth century, there was a real stigma associated with "brain fever," a catch-all term for neural sicknesses like meningoecephaliti and meningitis). After all, this was the era of both the rise of psychology and neurology, and the accompanying classification of mental disorders and illnesses. So Laura's rewriting of her sister's history was likely because scarlet fever was more palatable, not just more relatable. Laura is certainly not the first person to hide her family's secrets, or to rewrite her narrative. The tragedy of her own husband--Almonzo--is another example of how she reconstructed her past. But perhaps that's the greatest feat of a storyteller. Telling the story we want to hear, not what really happened. In this case, however, Laura's retelling has probably caused generations of people to associate scarlet fever with blindness, which is certainly incorrect. Yet another reason to constantly question what we read; to question what we know to be true. But what do you think? Murder, Mayhem and a Midwife...An interview with historian Sam Thomas, author of The Midwife's Tale1/8/2013  I'm excited to have historian Sam Thomas join me today to discuss his first novel, The Midwife's Tale, a historical mystery set in mid-seventeenth century York. Sam and I connected about a year ago, when we realized that (1) we're both trained as early modern English historians; (2) we both have debut novels coming out with Minotaur Books this year; and (3) both our mysteries are set in nearly the same time period. (I'm encouraging Sam to think about doing a cross-over piece, so that his midwife can bring my Lucy Campion into the world. But I digress.) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Official Description: It is 1644, and Parliament’s armies have risen against the King and laid siege to the city of York. Even as the city suffers at the rebels’ hands, midwife Bridget Hodgson becomes embroiled in a different sort of rebellion. One of Bridget’s friends, Esther Cooper, has been convicted of murdering her husband and sentenced to be burnt alive. Convinced that her friend is innocent, Bridget sets out to find the real killer. Bridget joins forces with Martha Hawkins, a servant who’s far more skilled with a knife than any respectable woman ought to be. To save Esther from the stake, they must dodge rebel artillery, confront a murderous figure from Martha’s past, and capture a brutal killer who will stop at nothing to cover his tracks. The investigation takes Bridget and Martha from the homes of the city’s most powerful families to the alleyways of its poorest neighborhoods. As they delve into the life of Esther’s murdered husband, they discover that his ostentatious Puritanism hid a deeply sinister secret life, and that far too often tyranny and treason go hand in hand. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------  A midwife at work The Midwife's Tale is told through the first person perspective of Lady Bridget Hodgson, a 30-year old twice-widowed midwife and real historical figure. How much is known of the true Bridget, and how much of her personality/character did you invent? Did you ever feel constrained writing a fictionalized account of a real person? That’s a great question! We know a fair bit about Bridget, and I include some of it here. A lot of the basics are true: She was twice widowed, first to a man named Luke Thurgood, then to Phineas Hodgson, who was the son of the Lord Mayor of the York. (And yes, Phineas seems to have been every bit the loser I portray him as.) Bridget also had a deputy named Martha, though I had to invent much more of her background. It is also pretty clear that she was a very strong woman. She came from an ancient family and wanted people to know it. She also named all of her goddaughters (as well as her own daughter) ‘Bridget’, presumably after herself. Who does that? I did, however, make some cuts. For my first book I had a heck of a time writing her home life, so I made her childless, though the historical Bridget was survived by two daughters. There are also rumors that she had two sons, both of whom were hanged as highwaymen, which is amazing, but I’m not sure I believe it.  Bridget's Will Similarly, is the case at the heart of The Midwife's Tale based on a true case from the archives? How did you go about doing your research? The case itself is entirely fictional, though a lot of the supporting characters are real. As for the research it was a lot of digging. I stumbled across Bridget’s will when I was working on another project, and it provided dozens of names for me to chase down: friends, family, and best of all, godchildren, which allowed me to identify a handful of clients. Once you have names, you can then dig into baptismal registers, tax records, probate documents, legal records, histories of York…it’s endless, really. I also got very lucky that Bridget was once sued for defamation, which allowed me do dig even further into her social life and the history of her practice. Besides being a compelling read, your story gets at some of the larger historical themes around gender, politics and religion that shaped this time period. In what ways did you consciously try to illuminate these larger trends? How did you balance the need for historical accuracy with creative license? I consciously wanted to connect ‘big’ and ‘little’ history. The novel takes place in the midst of a rebellion against the king, so I made the crime at its heart a domestic rebellion in which a wife is accused of murdering her husband. This was a time when people were intensely concerned about maintaining order at the national and domestic levels, and I wanted to see how they would react when that order was challenged. (Oddly – or not – I do much the same thing in my historical work, favoring microhisotry, in which big stories are told through the lives of average individuals.) In doing your research, what was one of the most interesting things you learned? I think it was how complicated life as a midwife could be. Not only did they deliver children, they were part of the legal system, investigating crimes ranging from infanticide, to rape, to witchcraft. It really makes midwives the perfect sleuths!  The beau's academy, 1699 Wing / 2854:35 In honor of the new year, I thought I'd offer some words of wisdom from the late 17th century. Granted, these words came from Edward Phillips, The beau's academy, or, The modern and genteel way of wooing and complementing after the most courtly manner (1699). So basically a book on how to be witty with the ladies. I selected a few of Phillips' -er- wisest statements and accompanying commentary (although a few are a tad hard to understand).

On prudent spending: He that spends beyond his ability, may hang himself with great agility. For he is lighter than he was by many a pound. (I have to say, this is one of Phillips' more sensical statements!) On the perils of whispering sweet nothings: Good words cost nothing. Unless it be love verses, for some men do pay. On fighting: He that cannot fight let him run. Tis a notable piece of Machiavelian policy. (I'm envisioning some poor battle-shocked Redcoats being relieved of their weapons and released to the elements....Machiavelian indeed!) On cooking: Better no pies, than pies made with scabby hands. (um, definitely one to keep in mind!) He's an ill cook that licks not his own fingers. (Methinks Tom Colicchio would concur!!!) On being a good provider: Good at meat, good at work. Therefore, 'tis the best way always to eat stoutly in the presence of women. (Got that, men?) ...and a few I can't easily categorize, but which sound a little naughty: Of idleness, comes no goodness. For that is the reason so many maids have the green sickness. (The "green sickness" [chlorosis or hypochromic anemia] was once considered "pecuilar to virgins." So being idle won't do anyone any good!) Hungry dogs love dirty puddings. There's many a man hath lost his nose by verifying this proverb. (I'll let someone else interpret this one!) Just a little something to ponder!!!  the codes in the fire poems... There's been sort of a funny game of tag going among writers recently, called "The Next Big Thing." So crime fiction writer Holly West was kind enough to tag me, which means it's my turn to answer some writerly questions and tag some other writers. 1) What is the working title of your next book? After A Murder at Rosamund's Gate releases April 23, 2013 (sigh, yes, I'm still awaiting this great moment), my next book featuring Lucy Campion is From the Charred Remains. That's still my working title at the moment, although I will probably change it when the book gets closer to publication (in 2014). 2) Where did the idea come from? FTCR continues two weeks after A Murder at Rosamund's Gate leaves off; that is, directly after the Great Fire of London in 1666. So many people, including Lucy, were pressed into service to assist in the great clean-up after the Fire. I thought for sure secrets would have to emerge from charred remains. Of course, plucky Lucy has to be the one to encounter an intriguing puzzle.... 3) What genre does your book fall under? FTCR is a mystery, and within that historical fiction and traditional. I'm not quite sure if readers at Danna's awesome cozy mystery blog would call it a cozy or not, but like Anne Perry's books, it has elements of a cozy.  4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition? I don't want to give away my thinking completely (since I prefer readers to imagine characters for themselves) but I wouldn't be adverse to the compelling Michael Kitchen (Foyle's War) portraying my kindly magistrate. 5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book? Ack! The dreaded one-sentence synopsis. Torture to the writer! Here goes... Lucy Campion, a chambermaid turned printer's apprentice, discovers in the aftermath of the Great Fire the body of a murdered man; on his corpse, she finds a poem which she publishes, little realizing that this act would bring her once again into direct confrontation with a murderer. 6) Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency? I am represented by the amazing David Hale Smith of Inkwell Management. Both books will be released by Minotaur Books (St. Martin's Press). 7) How long did it take you to write the first draft? Given that A Murder at Rosamund's Gate took me about ten years to write (seriously!) I'm amazed to say that I wrote FTCR in just a few months. 8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre? I've been inspired by both Anne Perry and Rhys Bowen. 9) Who or what inspired you to write this book? I've been inspired to write these stories ever since I was a doctoral student of history. My husband and kids inspire me every day to keep pursuing my dream... 10) What else about the book might pique the reader's interest? If you like puzzles and codes, this one is for you... On Dec. 19, please be sure to check out these awesome writer's blogs...

Anna Lee Huber, The Anatomist's Wife Helen Smith, Alison Wonderland  1631 STC /1476:06 Riddles, jests and other merriments always sold well in seventeenth-century England. Then, as now, people enjoyed a good laugh--being surrounded by plague, terrible sickness, fire, Puritans, etc may have had something to do with that! When I came across A Book of Merrie Riddles--claimed to be "very delightful for youth to try their wits"--I couldn't resist offering a few to YOU. Let's see what you make of these seventeenth-century jests. First, I'll give you few questions with solutions. Then, I'll give you a few without; see what you come up with. Question: I wound the heart and please the eye. Tell me what I am, by and by. Solution: Beauty. Question: When I did live, then was I dumb, and yield no harmony: But being dead, I do afford most pleasant melody. Solution: Any musical instrument made of wood. Easy, right? Of course there are a few a little more inscrutable today: Question: Who wears his end about his middle once in his time? (I would let you figure out this one, but it's pretty contextually situated.) Solution: A thief whose arms are tied with the halter, wherewith he shall be executed. Hmmm.... So here are a few more...what do you think are the solutions? Question 1: I do walk, yet I do not go. I do drink, yet no thirst lack; I do eat, yet do not feed; I do wake, yet no work make. What am I? And another: Question 2: I was not, I am not, I shall not be, yet I do walk as men do see. What am I? ********************************************************** Let me know: Are you as smart as a 17th century youth? I'll post the answers soon..... *********SPOILERS!!! Solutions ahead!!!***************

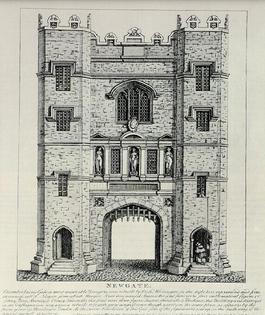

I figure that's sufficient space, if you're really concerned. Question 1: so, so, SO LAME. The solution is "Someone moving about in a dream." Question 2: so, so, so, SO, SO, SO LAME! (or fiendishly clever, you decide). The solution is "A person with the surname of 'Not'." As in Susie Not. NOT!!!  After Newgate burned down, then what? When I wrote the first draft of From the Charred Remains, I focused mainly on getting the story worked out--finding the heart and shape of my tale. I didn't stress too much over language, description, and dialogue on the first go-round--I figured I could elevate my prose later. As for historical details, I frequently had to make my best educated guess about what might have been true in those first weeks after the Great Fire of London (September 1666)...and move on. Now as I work through draft two, I'm doing the hard--I mean fun--part: Fixing and double-checking all the historical details. I've already mentioned two of my recent questions (How plausible was the stated death toll of the Great Fire of London?) and (How far could a horse travel in the seventeenth-century anyway?), but here are a few other things that I've pondered: Since my heroine is now a printer's apprentice (yes, unusually so!) I had to figure out a lot of specifics about the early booksellers and their trade. So I wondered, for example, how did a seventeenth-century printing press operate? As it turns out, the press operated in a remarkably gendered way--parts of the machine were referred to as "female blocks," which had to connect with "male blocks." The interconnected parts were supposed to work together harmoniously, but on occasion--usually when the female "leaked"--the whole press might stop working. (Naturally, the female part was to blame!) And another question: Since three of the largest prisons--Newgate, Fleet, and Bridewell--were all destroyed in the Great Fire, where were criminals held? I had to make my best guess on this one. There were other prisons of course: Gatehouse prison in Westminster, the White Lion prison, the Tower, and my favorite, the Clink in Southwark. But I decided to invent my own makeshift jail--after all, in those chaotic days after the Great Fire, order had to be regained quickly, and it stands to reason that royal and civil authorities might have wanted lawless behavior contained as quickly as possible. I couldn't find evidence to the contrary, so an old chandler's shop became a temporary jail. And were criminals still being hanged at the Tyburn tree immediately after the Fire? Executions resumed quickly after the Fire, conducted as they had been since the twelfth century, in the village of Tyburn (now Marble Arch in London). Prisoners were progressed by cart, from jail to the "hanging" tree, parading through the streets--often praying, preaching, repenting or depending on their personality, even swapping jokes with the spectators. Usually they stopped at a tavern for one last drink along the way, before being forced to do the "Tyburn jig," as Londoners cheerfully called execution by hanging. Of course, I also looked up countless other details...Who used acrostics and anagrams to convey messages? What secrets might be conveyed in a family emblem? And most significantly of all: What happened when the first pineapple arrived in London? Ah-h-h, but I can't tell you about these answers....I'd be giving too much away about Book 2!!! I don't really have a question for you to answer, so I'll just end with a maniacal laugh... MWAH HA HA HA HA....!!! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed