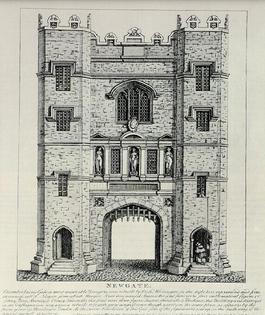

After Newgate burned down, then what? When I wrote the first draft of From the Charred Remains, I focused mainly on getting the story worked out--finding the heart and shape of my tale. I didn't stress too much over language, description, and dialogue on the first go-round--I figured I could elevate my prose later. As for historical details, I frequently had to make my best educated guess about what might have been true in those first weeks after the Great Fire of London (September 1666)...and move on. Now as I work through draft two, I'm doing the hard--I mean fun--part: Fixing and double-checking all the historical details. I've already mentioned two of my recent questions (How plausible was the stated death toll of the Great Fire of London?) and (How far could a horse travel in the seventeenth-century anyway?), but here are a few other things that I've pondered: Since my heroine is now a printer's apprentice (yes, unusually so!) I had to figure out a lot of specifics about the early booksellers and their trade. So I wondered, for example, how did a seventeenth-century printing press operate? As it turns out, the press operated in a remarkably gendered way--parts of the machine were referred to as "female blocks," which had to connect with "male blocks." The interconnected parts were supposed to work together harmoniously, but on occasion--usually when the female "leaked"--the whole press might stop working. (Naturally, the female part was to blame!) And another question: Since three of the largest prisons--Newgate, Fleet, and Bridewell--were all destroyed in the Great Fire, where were criminals held? I had to make my best guess on this one. There were other prisons of course: Gatehouse prison in Westminster, the White Lion prison, the Tower, and my favorite, the Clink in Southwark. But I decided to invent my own makeshift jail--after all, in those chaotic days after the Great Fire, order had to be regained quickly, and it stands to reason that royal and civil authorities might have wanted lawless behavior contained as quickly as possible. I couldn't find evidence to the contrary, so an old chandler's shop became a temporary jail. And were criminals still being hanged at the Tyburn tree immediately after the Fire? Executions resumed quickly after the Fire, conducted as they had been since the twelfth century, in the village of Tyburn (now Marble Arch in London). Prisoners were progressed by cart, from jail to the "hanging" tree, parading through the streets--often praying, preaching, repenting or depending on their personality, even swapping jokes with the spectators. Usually they stopped at a tavern for one last drink along the way, before being forced to do the "Tyburn jig," as Londoners cheerfully called execution by hanging. Of course, I also looked up countless other details...Who used acrostics and anagrams to convey messages? What secrets might be conveyed in a family emblem? And most significantly of all: What happened when the first pineapple arrived in London? Ah-h-h, but I can't tell you about these answers....I'd be giving too much away about Book 2!!! I don't really have a question for you to answer, so I'll just end with a maniacal laugh... MWAH HA HA HA HA....!!!

4 Comments

Matt

9/16/2012 06:27:36 am

[Chanting] BOOK TWO...BOOK TWO...BOOK TWO!

Reply

bekerys

9/22/2012 05:32:52 am

When pineapples came to England, no one had a clue what to do! They are spiny, ugly, unpleasant tasting fruits that aren't even good for feeding pigeons!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed