Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Every morning, when I check my email, I'm reminded of a funny (funny-weird, not funny-humorous) thing about book titles. Because I have a daily Google alert on my titles, I get a little summary about how they have used been used on the internet. For my first novel A Murder at Rosamund's Gate and for my third novel, The Masque of a Murderer, I get alerts that actually pertain to my book. But for my second book, From the Charred Remains, I am treated to all sorts of terrible and strange news stories--usually house fires--of things or people being found after a fire (this gem to the right is one of the better things that's come this way). Literally, this illustrates the dark side of book titles. There are terrible things that happen in the world--beyond what happened on the mythical Tatooine--and every day those come to my inbox because of how I titled my book. I shouldn't be surprised--after all, the premise of my book is that a body has been found in a barrel outside the Cheshire Cheese after the Great Fire has devastated much of London. So as I sort though new titles for my fourth book--the soon to be renamed Stranger on the Bridge--I find myself avoiding titles that reporters might use to describe particularly grisly stuff. It's ironic really. The title of my first book didn't make it through marketing, but it was originally called Monster at the Gate. I thought the concept of monster fit well with my time period, but that title was deemed too harsh and supernatural. I can only imagine the kinds of Google hits I would have gotten, had I kept that title. The original title of my third book, Whispers of a Dying Man, didn't make it past my own internal scrutiny. Bleagh. Glad I changed that one. The Masque of a Murderer is a much better title. But From the Charred Remains sailed through easily. I still like the title, but I'm still a bit wary when I see what Google has sent me. Now, I'm still pondering the title of my fourth book. Stranger on the Bridge just isn't resonating for me. So at New Year's, after describing the premise, I asked a bunch of my friends to all put single words (nouns and adjectives) into a hat. Then we all picked three or four slips of paper and formed titles. The best of this admittedly drunken endeavor was Across the Misty Divide. Probably won't go over either (sorry Steve!). Maybe the parlor game method of naming books is not the best method. So hopefully something connects soon!!! I'll keep you posted!

1 Comment

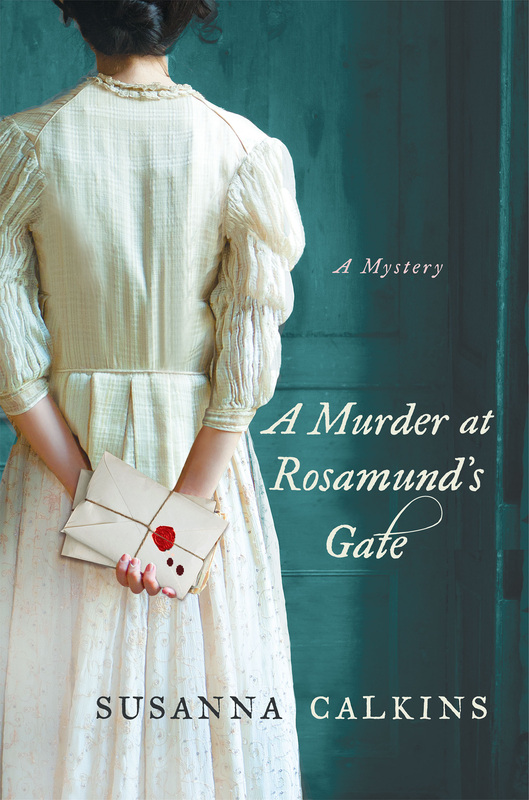

Life has been crazy, crazy, CRAZY busy...I've barely had any time to post. Work is, well, busy, on top of that I just finished up teaching two classes and now I'm prepping for the next quarter, and I'm still working away on Book 3--The Masque of a Murderer--due to my editor very soon. All the while I'm trying to gear up for the launch of Book 2--From the Charred Remains--which will be released on April 22. Yikes and a half! But it's fun to take time out to celebrate the different writing milestones. Today my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, came out in paperback. I even signed a few copies, just for fun!  In seventeenth-century England, the role of servants was far more nuanced and flexible than readers today may realize. Certainly, there was a long-standing patriarchal expectation that the head of a family would maintain a godly and dutiful order over his household. In advice manuals, published letters and sermons, men were repeatedly admonished on how to treat the servants living in their homes. Men were expected to provide food, shelter, religious instruction, and a disciplined hand, much as they were expected to treat their own children and wives. They were not supposed to treat their servants as slaves; indeed, quite the opposite. However, we must always consider the tensions between prescription and practice. Just because the expectations were stated, most certainly does not mean that the expectations were met. For example, in Advice of a father, or, Counsel to a child (1664), men were admonished to:

For this reason, as the last injunction suggests, discretion was particularly important (perhaps because it was not always be realized). The Early English Books are full of tales of servants blackmailing their employers, because they had discovered something the master (or mistress!) would rather have kept hidden (e.g. adultery, gambling debts, infanticide etc). Thus, the same advice manual warns:

This last point suggests that even the lowest servant in his employ should be treated as all the other servants were treated.While the master was expected to rule with a firm hand, he was more like a benevolent monarch than a tyrant:

There's a pragmatic realization here that seems to transcend the ages. If you work someone without letting them "blow off steam," then you run the risk of having unmotivated, even hostile or violent, servants in your household. This holds with the reality of homicide trends in the 17th century: Far more servants killed their masters, than masters killed their servants! This injunction also fits in with the many accounts across the Early English books of servants getting some days off, attending the theatres and fairs, going to market, visiting family, even sharing in merriments with the family. While the author of this piece would mostly likely call for moderation, it's clear that masters did give their servants more freedoms than might be assumed.  Anon. (1664). Advice of a father Anon. (1664). Advice of a father I want to point out one other piece of advice offered in this manual: "Reckon thy servants among thy children; the difference is only in degrees; both make up the economy; thou art the father of the family; a wife servant is better than a foolish child; cast him not off in an old age, when he has spent himself in thy service; a faithful servant does well deserve to be counted among thy friends." There was, without a doubt, a recognition that loyal servants could become more like members of the family over time. In this particular injunction, the master is told not to throw out his servants just because they have become old, but rather to take care of them. The best example I can think of, to help illustrate how a servant could become like a family member over time, is to draw on a 1960s reference: Would the Brady Bunch have thrown out Alice? In my recent novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, I touch on a lot of these issues. I deliberately placed my protagonist Lucy Campion, in the household of a magistrate, at a time when Enlightened principles were starting to emerge in England. In my story, I deliberately juxtapose the reasoned household of the magistrate, with the less disciplined households that surrounded them. I wanted my magistrate then to be a more Enlightened thinker, more concerned with ideas, than the person who suggested those ideas to him. So he could have listened to and believed in the views of a servant with an intelligent lively mind. Perhaps I gave Lucy too many freedoms, perhaps I didn't. Ultimately, I do not think there is any blanket, all-encompassing way to look at the relationship between masters and servants in 17th century England. Arguably, these attitudes may have changed in the 18th and 19th century (although I doubt there was a monolithic understanding of this relationship even then), but the bottom line is this: The relationship between master and servant in the 17th century was far more nuanced and flexible than is often assumed. This is my story, and I'm sticking to it!  My book started years ago, when I was a graduate student, pouring over 17th century murder ballads. The ballads served as musical 'true accounts' of murderers who wrote letters to their victims, urging them to rendezvous in dark deserted fields. I knew I had to write about these monsters. I drank lots of coffee.  I spent years writing this first book, scene by scene, in little half hour bursts, at coffee shops, on the train, when the kids were sleeping, until one day--in 2010-- I finished. Even my husband--alpha reader extraordinaire--did not know much about the story. "It's set in the seventeenth century," I'd mumble. "A servant gets killed. Another servant tries to figure it out. Stuff like that." But eventually, I asked him and a few other trusted friends to read the book. I revised again, queried, queried, queried, while writing an entirely different book in the interim. In 2011, I got my wonderful agent who quickly connected me to my equally wonderful editor at Minotaur. My journey was no longer an imaginary jaunt; the path to publication was suddenly very real.  In 2012, more changes happened. The title of my book got changed. My publication date got pushed back. My beautiful cover was revealed. Multiple revisions happened. Copy edits made me crazy, but I learned a lot in the process. I had my first public appearance as a novelist ("2 minutes at Bouchercon"). At some point, I received my ARCs. 2013. Months still passed. My book began to be publicized. I reached the 100 Day mark. Another few months passed. My book started to be reviewed. My hardback copy came in the mail. And now...Be still my heart... MY BOOK IS FINALLY HERE!!!!

Thanks to all my colleagues, friends and family--especially my husband--who made this possible!!!!  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.  Just a hundred days left until A Murder at Rosamund's Gate is released on April 23, 2013!!! Now, I know you might well be thinking: "Um, didn't your book come out, like, a year ago? You've been talking about it for ages." Nope. The book has just been gestating, percolating, spinning, whirling, stirring for the last eighteen months. What can I say? Publishing is a mysterious business. A hundred days! A hundred days! Historically, the Hundred Day mark has been a crucial signifier:

Okay, so the last 100 days before my book gets published is not quite so significant in comparison. And I'm pretty sure that the journey won't be a "do or die" march towards triumph or defeat a la Napoleon or FDR. But given that I've been waiting my whole life for this moment... JUST A HUNDRED DAYS TO GO is an awfully exciting concept!!!  the codes in the fire poems... There's been sort of a funny game of tag going among writers recently, called "The Next Big Thing." So crime fiction writer Holly West was kind enough to tag me, which means it's my turn to answer some writerly questions and tag some other writers. 1) What is the working title of your next book? After A Murder at Rosamund's Gate releases April 23, 2013 (sigh, yes, I'm still awaiting this great moment), my next book featuring Lucy Campion is From the Charred Remains. That's still my working title at the moment, although I will probably change it when the book gets closer to publication (in 2014). 2) Where did the idea come from? FTCR continues two weeks after A Murder at Rosamund's Gate leaves off; that is, directly after the Great Fire of London in 1666. So many people, including Lucy, were pressed into service to assist in the great clean-up after the Fire. I thought for sure secrets would have to emerge from charred remains. Of course, plucky Lucy has to be the one to encounter an intriguing puzzle.... 3) What genre does your book fall under? FTCR is a mystery, and within that historical fiction and traditional. I'm not quite sure if readers at Danna's awesome cozy mystery blog would call it a cozy or not, but like Anne Perry's books, it has elements of a cozy.  4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition? I don't want to give away my thinking completely (since I prefer readers to imagine characters for themselves) but I wouldn't be adverse to the compelling Michael Kitchen (Foyle's War) portraying my kindly magistrate. 5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book? Ack! The dreaded one-sentence synopsis. Torture to the writer! Here goes... Lucy Campion, a chambermaid turned printer's apprentice, discovers in the aftermath of the Great Fire the body of a murdered man; on his corpse, she finds a poem which she publishes, little realizing that this act would bring her once again into direct confrontation with a murderer. 6) Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency? I am represented by the amazing David Hale Smith of Inkwell Management. Both books will be released by Minotaur Books (St. Martin's Press). 7) How long did it take you to write the first draft? Given that A Murder at Rosamund's Gate took me about ten years to write (seriously!) I'm amazed to say that I wrote FTCR in just a few months. 8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre? I've been inspired by both Anne Perry and Rhys Bowen. 9) Who or what inspired you to write this book? I've been inspired to write these stories ever since I was a doctoral student of history. My husband and kids inspire me every day to keep pursuing my dream... 10) What else about the book might pique the reader's interest? If you like puzzles and codes, this one is for you... On Dec. 19, please be sure to check out these awesome writer's blogs...

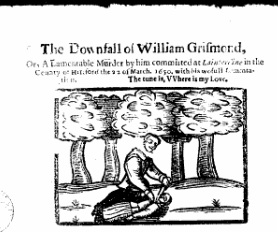

Anna Lee Huber, The Anatomist's Wife Helen Smith, Alison Wonderland  Wing / 2705:15 A recent post by author Eric Beetner on Holly West's blog has made me deeply reflect on the way I think about writing. Eric, a musician as well as a writer, was discussing the important role that music plays in his crime fiction. Eric uses music to add dimension to his characters, explaining "Music can be an effective way to get to know a character since music is very personal." We see this all the time in film, especially to set a mood, but I'm not sure how common this is in novels. But as I thought about it, I have used music to emphasize key themes in my writing, but in a very different kind of way from what Eric describes. The murders in my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, are largely described through ballads, broadsides and other penny pieces... which is how 17th century Londoners would have learned about crimes within their community. Murder was literally described in verse, sung by booksellers on street corners, in a sort of a half fictional, half truthful way. Take, for example, this 1660s ballad which I chose at random from the Early English Books--a large collection of penny press from the 16th to the 19th centuries. As always, the title provides a synopsis to the reader (or listener, as neighbors and friends would read these ballads out loud): The downfall of William Grismond: or, A lamentable murder by him committed at Lainterdine in the county of Hereford, the 22 of March, 1650, with his woful [sic] lamentation.  If you just look at the first part, you'll see the author specifies that the murder ballad should be sung to the tune of "Where is my love." (Ironic, of course, given that his love is lying on the ground, having been murdered at his hands. The audience would have gotten the joke). But the point is that the story wasn't meant to be just read, but sung according to a well known popular tune. Somewhere along the way we may have lost this connection between music and fiction-writing. Obviously, a lot of musicians are story-tellers, but I'm not sure how many novelists frame their stories musically.

So I'm curious...If you write, do you deliberately use music as a way to develop themes, characters, mood etc? If you are a reader, do you hear a soundtrack play as you read? Do you want to?  Interacting with Mars The other day a faculty member who teaches college science courses shared with me an innovative method he uses to enhance critical and creative thinking in his students. Instead of having his students complete more traditional reports on scientific principles and concepts, he has them create science fiction stories, drawing on those same scientific ideas. (Boy would I have loved science if my professors had asked me to do that!). As we talked, we discussed the necessity of not just asking students to sprinkle scientific details through their stories, but rather the importance of having their characters engage with those details. This would add to the scientific authenticity. More importantly, I think they contribute to the overall richness of the story. So, for example, a writer could just passively describe Mars: "The floor of the Gale Crater was grayish-blue in color. Brown and gray pebbles were strewn everywhere. At the center of the crater was Mount Sharp. Without any sign of life, Larry thought it was definitely the perfect place to land the Motherland's craft." Or, the characters could actively engage with the Martian terrain--as they would engage with another character: "As Larry stepped cautiously down from his craft, his boot sunk a little deeper down into Gale Crater than he had expected. What he had thought would be thickly-layered bedrock was actually more sponge-like in its composition. This was not the first time the Motherland's Minister of Science had been wrong about a planet. He kicked one of the many brown pebbles strewn across the landscape. "It's going to take me forever to get to Mount Sharp," he muttered to himself. "Why'd the General tell me to land here? The mountain's at least three kilometers to the north." Shivering, he checked the temperature gauge on his suit. 66 degrees. "Geez, it's dropped at least 10 degrees since I landed." Out of the corner of his eye, he saw one of the pebbles move. "Uh, oh." He groaned. "That's no pebble!" Okay, there's a reason I don't write science fiction. But when I was first embarking on my novel-writing journey, I learned about the concept of treating description, scenery, weather, etc as another character. Details should be added to enhance the experience of a character. In A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, for example, I turned the ever-present London fog into a character--alternatively gentle and tempestuous in turns. Of course, this is a matter of taste. There are plenty of great books out there--especially some of my favorite nineteenth century novels--that have PAGES and PAGES of description without a bit of dialogue or action to break them up. But I admit, I probably skim long passages of description for the most part. How about you? Do you enjoy books with lots of scenic descriptions? Or do you prefer when characters engage with the scenery, as they would engage with another character?  The alpha reader wolf This weekend, I'll be working on the first set of suggestions for my second novel, From the Charred Remains, compliments of my alpha reader (a.k.a my dear husband Matt). Even though I sometimes gnash my teeth and grimace over his comments ("Who cares if I start three sentences in a row with "And"? "What do I care what color this character's eyes are?"), I think he gives really good comprehensive feedback. So I asked him to offer his insights into what it's like to make suggestions on a novel in progress. (Disclaimer--he says some nice things in here about me, which I really didn't make him say). ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I’ll never forget the moment that I finished reading the very first draft of A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate. After years of knowing next to nothing about the novel, suddenly all had been revealed. (So true, I never told him I was writing a novel. --SC) I remember feeling many emotions, with pride and awe being the most salient. I recall thinking, “Wow, this feels like a novel that people buy from Barnes & Noble! How did she create this vivid world and these vibrant characters? How did she develop this compelling mystery that kept me guessing until the end? How did she weave such interesting historical details into story? Just wow.” Then came feelings of satisfaction and contentment—“What a great ending”—and a yearning for more—“I miss Lucy already. I wonder what will happen in the next book?!?” After sharing these thoughts with Susie, she reminded me that the other duty of the alpha reader is to provide constructive feedback. I remember feeling ill-equipped for this task. “Who am I to give a critique? I’ve never written a novel and I doubt that I ever could. What can I offer that would be of any value?” During my careful rereads of various drafts, I learned that I could provide some valuable feedback (e.g. "Why would this character do that?" "I thought you said it was raining outside," or "You know you said this character was dead--what is he doing talking to Lucy?"). Susie subsequently rewarded me with a variety of titles: Vice President of Continuity Management, Head of Repetition Detection, and Director of Necessity Questioning. Although these titles are simply meant for fun, I take great pride in them and I am thrilled that Susie asked me to continue in these roles for book two: From the Charred Remains! Having recently read the first draft of FTCR, I found myself filled again with awe and pride—“How did she do it again?”—and a yearning for more—“When will book three be ready?!?” Can you relate to any of these experiences? Feelings of pride and awe in the accomplishment of someone close to you? The tough position of providing constructive feedback? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed