|

I received a query from a reader yesterday that gets at the many meddlesome and troublesome questions that writers of British historical fiction inevitably face--How do nobles address each other? "...I just wanted to know: if the oldest daughter of an earl was going to soon be marrying the oldest son of another earl, how would they address one another? The setting is 1860s London, if this helps answer my question. I have read many websites and guide-books that explain how the peerage would be addressed by various people in various situations, but I am having trouble finding information about two people, both children of earls, who are engaged to be married. Would they be more casual with one another? Or would it be inappropriate to address one another without their appropriate title? Your help would be greatly appreciated. Thank you." --Maryam. This is indeed a tricky question. I know something about the forms of address in 17th century England, but I didn't want to assume what was common or expected in the 1660s would be the same 200 years later, in the 1860s. So I threw this question out to the lovely and talented Sleuths in Time, who have spent a lot more time than I have thinking about this question.

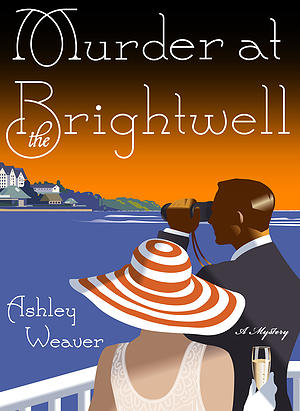

So, first, the basics. According to Tessa Arlen: "The eldest daughter of an earl would be called Lady Susan; that would be the extent of her title until she marries. If she were to marry an ordinary man she would be called Lady Susan and then his surname: Lady Susan Blogs for example. The eldest son of an earl might be given an honorary title of his father's of a lower rank this would be given to him until he inherited his father's title. For example, his father who is Roger Parker, Earl of Bainbridge might bestow the honorary title of viscount on his eldest son. So the son's name and title would then be Denis Parker, the Viscount Lord Winslow. It is also important to remember that the Earl of Bainbridge would have a family name, in this case Parker." This seems pretty straightforward so far, right? Tessa continues: "I can't imagine why this young couple would call one anything other than by the first names when they were alone together. And if they are English the usual terms of endearment! If they were together out in society Lady Susan would be referred to as the Vicountess Lady Winslow and her husband would be the Viscount Lord Winslow and they would be announced as Lord and Lady Winslow. When Lord Winslow's father dies and he inherits the earldom he will become the next Earl of Bainbridge - and be called Lord Bainbridge and his wife would become the Countess of Bainbridge. The order of precedence can be very confusing - even for Brits. So tell your friend to follow this pattern and she will sound like she knows what she is talking about!" Excellent advice! Alyssa Maxwell also commented: "Sometimes the son and heir would be called by his courtesy title without Lord in front of it, as in Brideshead or Bridey as friends and family called him in the book." She also directed us to Jo Beverley's Guide to English Titles in the 18th and 19th centuries, a very helpful resource! As Anna Lee Huber further notes: "In the case of an earl, he usually does have a lesser title (viscount or baron) he can grant his eldest son as a courtesy, but it's also possible he doesn't. (Author's choice since it's fiction.) In that case he would be called Mr. Parker by his fiancé in public, Denis in private. The rules for daughters & sons of earls are slightly different. Daughters of dukes, marquesses, & earls receive the honorary Lady before their first name. Only sons of dukes & marquesses receive the honorary Lord before their first name." And to round us out, Ashley Weaver says, "I have always found [Laura Chinet's] site really useful for reference. She has little charts and everything!" [I will say, however, that what Laura Chinet describes for the 18th and 19th century may be different from 17th century conventions. In my research, I have seen many letters between family members that use endearments, like "My dearest Anne." So it stands to reason that if they use such intimacies in written letters, they would do the same in private conversations. There is a formalization of speech and manners that happened in the mid 18th century that was not as pervasive in earlier centuries-SC]. Ultimately, in my opinion, this comes down to an accuracy vs authenticity kind of question. I think writers of historical fiction should try their best to be as reasonably accurate as possible, but ultimately their focus should be on telling the best story possible, without jarring the reader.

2 Comments

I'm delighted to say that recently a group of us--eight authors who write historical mysteries--joined together to form a new collective: Sleuths in Time, Tracking Crime. We write historical mysteries set in England, Scotland and the United States, ranging in time from the 1660s to the 1930s. Connect with us on Facebook and Pinterest (Sleuths in Time Authors) or follow us on Twitter! (@sleuthsintime). We've got some great things planned, including some giveaways and a scavenger hunt at Malice Domestic. Stay tuned for details!

|

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed