On my recent vacation, I finally got a chance to delve into a novel I've always wanted to read: THE MOONSTONE (1868) by Wilkie Collins, often considered the first modern detective novel. It also caused me to reflect a bit on my writing, and how important it is to consider the heart of each scene. The story is told through multiple narrators, including Gabriel Betteredge, the septegenarian steward of the household, charged with detailing the loss of the diamond--the mystery at the center of the novel. As a writer, I was immediately amused by the way that Betteredge set to writing his account. First, he consults his trusty ROBINSON CRUSOE, opening it at random as others might seek insights from a religious text:  "In the first part of ROBINSON CRUSOE, at page one hundred and twenty-nine, you will find it thus written: 'Now I saw, though too late, the Folly of beginning a Work before we count the Cost, and before we judge rightly of our own Strength to go through with it.'" A prophecy? he wonders. How could he set to writing such a momentous task? Could he see it through? Questions surely every author has pondered when staring at that first blank page before the story has begun. He then proceeds to speak at length at how well ROBINSON CRUSOE can answer all life's great mysteries. After a time though, he finally realizes he has not yet started the story he was tasked to write: "Still, this don't look much like starting the story of the Diamond--does it? I seem to be wandering off in search of Lord knows what, Lord knows where. We will take a new sheet of paper, if you please, and begin over again, with my best respects to you." So he begins his story again, this time how he came to serve in his lady's household, where the diamond was destined, and about how he came to marry his wife and have a daughter. Again he goes on at length, until he gets to the end of the passage: "My daughter Penelope has just looked over my shoulder to see what I have done so far. She remarks that it is beautifully written, and every word of it true. But she points to one objection. She says what I have done so far isn't in the least what I was wanted to do. I am asked to tell the story of the Diamond and, instead of that, I have been telling the story of my own self." Already off track, he then ponders further that idea that many authors probably think about: "I wonder whether the gentlemen who make a business and a living out of writing books, ever find their own selves getting in the way of their subjects, like me? If they do, I can feel for them." Then he starts the story one more time, this time with a little more desperation: "In the meantime, here is another false start, and more waste of good writing paper. What's to be done now? Nothing that I know of, except for you to keep your temper, and for me to begin it all over again for the third time." This may be surprising, but I think THE MOONSTONE offers an important lesson in finding the heart of a scene. In some ways, what the narrator Betteredge is doing is the kind of throat-clearing we often see writers do, particularly those with less experience. (To be clear, I am focusing on the words and thoughts of the character, not the actual author Wilkie Collins, who I think is brilliantly setting up the characters and the narrative). One of the things I've observed when critiquing the work of others--and this is certainly something I've struggled with myself--is how often writers (especially less experienced ones) do not start and end scenes in a particularly effective manner.

Many writers seem to just meander into a scene, as if they are strolling to an important event in town. Along the way to this event, they greet people, pop in and out of stores, talk on their cell phones, watch their dogs play, chase after kids, look at shapes in the clouds. Others meander away from an important event, without any plans on what they intend to do next. This may be fine in real life, but in writing, a scene should be more focused. I try to encourage writers to ask themselves questions: What is the goal of this scene? Does it advance a plot or subplot? Is it intended to reveal or continue a conflict? Is it meant to force a story forward? Is it intended to show a response to a conflict or dilemma? Does it indicate a decision or resolution (or even a seeming stalemate)? For me, even though I am a 'seat of the pants' kind of writer--a pantser--I find that asking these kinds of questions help me think through my intentions even as I go. This is not to say that scenes should follow some sort of template. One of the fascinating things about THE MOONSTONE is its unusual narrative structure (perhaps more common now, but certainly uncommon in its day). The scenes, though offered in a meandering way by the narrator, actually quite purposefully lay out the far-larger story of the diamond, dropping clues and intimations in a rather remarkable way. Getting to the heart of the story, by getting at the heart of each scene--is crucial. Otherwise, we'll be flailing about like Betteredge, "wandering off in search of Lord knows what, Lord knows where." And when your meandering tale can not be saved, pick up your quill, lay out a new sheet of paper and now, "refreshed in hope," re-start your story again.

2 Comments

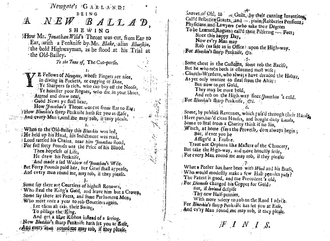

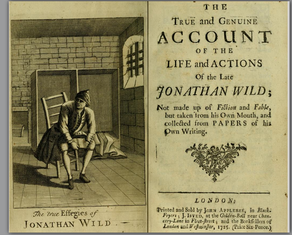

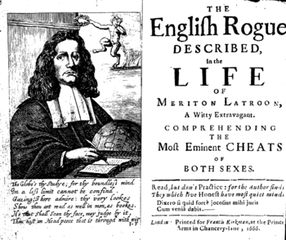

Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  _ When I was first writing Monster at the Gate, I toyed with the idea of writing the whole book in authentic seventeenth century prose. That idea lasted about two seconds. Partly because that trick's been done, you know, by actual writers from that time period, like Defoe. And partly because I thought readers might throw rotten tomatoes at me for writing in such a cumbersome manner (heck, I might throw them at myself). But mainly, it was because many seventeenth-century words and phrases don't translate readily today, and unless my editor lets me write a companion volume with glossary and explanatory footnotes, I don't think it would work (assuming I had the patience for such an endeavor, which I don't). For example, criminals and thieves created their own language, "cant," which was deliberately designed to hide their shadowy doings. Amazingly though, a few curious contemporaries, such as Richard Head, decoded this elusive criminal language in cant dictionaries (similar to modern slang dictionaries), basically as a public service to let their readers in on what the criminals were doing. So, for example, a thief might Bite the Peter or Roger (which our good Richard tells us means "steal the port-mantle or cloak-bag"), proceed to Tip the Cole to Adam Tyler ("give what money you pocket-pickt to the next party") , who might take it then to a stauling ken(a "house that wyll receaue stolen ware.") (I guess we'd say 'fence?'). Some phrases are even harder to translate. So, say a broadside depicts what happens to a criminal who is caught. It might read: “As the Prancer drew the Quire Cove at the Cropping of the Rotan through the Rum pads of the Rume vile, and was flog’d by the Nubbing-Cove.” Huh? Any guesses? No? Really? Well, according to J. Coleman's History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries (Oxford, 2004), that statement translates to: “That is, The Rogue was drag’d at a Carts-arse, through the chief streets of London and was soundly whipt by the Hangman.” You probably knew that. Awesome stuff! But I'm curious. Have you read any terrific (modern) books that were written completely in dialect? Did you find them hard-going? fun? or something in between? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed