Probably one of the most frequently asked questions I get from people seeking to write historical fiction is this: How much research should I include in my historical novel? And my reply, which may sound more flippant than I intend, is just this: Enough to tell the story. I've written elsewhere about balancing historical accuracy and authenticity. So, I thought today I'd given an example of how I seek to have my characters interact with historical details, hopefully without just dumping my research on my readers. I could have picked any passage, but in honor of Easter, I picked an excerpt from my forthcoming novel, A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET. In this, scene Master Aubrey has just returned from selling pamphlets (unsuccessfully) on Maundy Thursday, (known in other parts of the world as "Holy Thursday.") There were a couple of factual details about Easter that I wanted to bring up in the scene. First, since the Middle Ages, there was a tradition in England that on Maundy Thursday, the monarch would give money to the poor and wash the feet of twelve poor people. [Indeed, while the etymology is not certain, the word "Maundy" may have come from the Latin world mendicare ("to beg.")] But we know from the diarist Samuel Pepys, in 1667, King Charles II opted against the practice that year, asking the Bishop of London to do it for him. Second, there had been an ongoing debate about the moveable date of Easter--some scholars of the time insisted that the date should be the same each year, similar to how Christmas was always on December 25. Third, in general, I wanted to allude to the fact that England was on a different calendar (the Julian Calendar) than Catholic nations like France and Italy, which had adopted the calendar created by Pope Gregory (the Gregorian Calendar). I couldn't use all the research I had at my fingertips, but I tried to work in a few of the more salient points within their trade as the printers and sellers of books. So you can see what details I managed to include...  John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 Master Aubrey laid his pack down. “I sold a few. I went to Whitehall to see the King wash the feet of the poor people, but the Bishop of London did it on his behalf.” The printer seemed a bit disgruntled. It had long been the custom for the monarchs of England to wash the feet of twelve men and women, as Jesus had washed the feet of the Apostles before the Last Supper. Having the Bishop of London take on the task instead of the king clearly irked him. Sometimes Lucy suspected the printer had Leveller sensibilities and liked it when the royals took on more mundane responsibilities. “Which pieces did you bring?” Lucy asked, changing the subject. In truth, she was always intrigued to know how the packs got decided. Master Aubrey had a knack for knowing what to sell to attract a crowd that she desperately hoped to learn for herself one day. “Could not very well sell murder ballads and monstrous births on Maundy Thursday, hey? Brought along John Booker’s Tractatus paschalis and John Pell’s Easter Not Mis-Timed. Too many of them, it seems. Only the sinners’ journeys, like the one you wrote about that Quaker, sold today.” He kicked the still-full bag, looking in that moment a bit like Lach, causing Lucy to hide a smile. A rare miss for Master Aubrey. Most people did not care how the date of the moveable holy day was affixed in the almanacs each year. Nor did they care why Catholic nations celebrated Easter and Christmas on different days than they did in England. I'm sure some readers might think that I have provided too much detail here, and other people think I have not offered enough. But, for me, this was "enough to tell the story."

0 Comments

I received a query from a reader yesterday that gets at the many meddlesome and troublesome questions that writers of British historical fiction inevitably face--How do nobles address each other? "...I just wanted to know: if the oldest daughter of an earl was going to soon be marrying the oldest son of another earl, how would they address one another? The setting is 1860s London, if this helps answer my question. I have read many websites and guide-books that explain how the peerage would be addressed by various people in various situations, but I am having trouble finding information about two people, both children of earls, who are engaged to be married. Would they be more casual with one another? Or would it be inappropriate to address one another without their appropriate title? Your help would be greatly appreciated. Thank you." --Maryam. This is indeed a tricky question. I know something about the forms of address in 17th century England, but I didn't want to assume what was common or expected in the 1660s would be the same 200 years later, in the 1860s. So I threw this question out to the lovely and talented Sleuths in Time, who have spent a lot more time than I have thinking about this question.

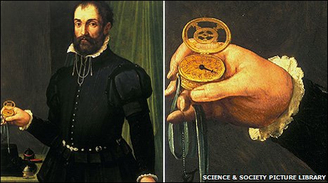

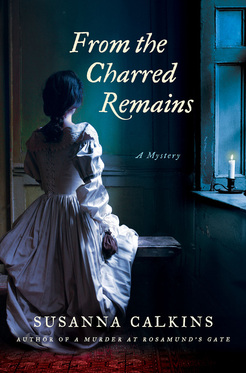

So, first, the basics. According to Tessa Arlen: "The eldest daughter of an earl would be called Lady Susan; that would be the extent of her title until she marries. If she were to marry an ordinary man she would be called Lady Susan and then his surname: Lady Susan Blogs for example. The eldest son of an earl might be given an honorary title of his father's of a lower rank this would be given to him until he inherited his father's title. For example, his father who is Roger Parker, Earl of Bainbridge might bestow the honorary title of viscount on his eldest son. So the son's name and title would then be Denis Parker, the Viscount Lord Winslow. It is also important to remember that the Earl of Bainbridge would have a family name, in this case Parker." This seems pretty straightforward so far, right? Tessa continues: "I can't imagine why this young couple would call one anything other than by the first names when they were alone together. And if they are English the usual terms of endearment! If they were together out in society Lady Susan would be referred to as the Vicountess Lady Winslow and her husband would be the Viscount Lord Winslow and they would be announced as Lord and Lady Winslow. When Lord Winslow's father dies and he inherits the earldom he will become the next Earl of Bainbridge - and be called Lord Bainbridge and his wife would become the Countess of Bainbridge. The order of precedence can be very confusing - even for Brits. So tell your friend to follow this pattern and she will sound like she knows what she is talking about!" Excellent advice! Alyssa Maxwell also commented: "Sometimes the son and heir would be called by his courtesy title without Lord in front of it, as in Brideshead or Bridey as friends and family called him in the book." She also directed us to Jo Beverley's Guide to English Titles in the 18th and 19th centuries, a very helpful resource! As Anna Lee Huber further notes: "In the case of an earl, he usually does have a lesser title (viscount or baron) he can grant his eldest son as a courtesy, but it's also possible he doesn't. (Author's choice since it's fiction.) In that case he would be called Mr. Parker by his fiancé in public, Denis in private. The rules for daughters & sons of earls are slightly different. Daughters of dukes, marquesses, & earls receive the honorary Lady before their first name. Only sons of dukes & marquesses receive the honorary Lord before their first name." And to round us out, Ashley Weaver says, "I have always found [Laura Chinet's] site really useful for reference. She has little charts and everything!" [I will say, however, that what Laura Chinet describes for the 18th and 19th century may be different from 17th century conventions. In my research, I have seen many letters between family members that use endearments, like "My dearest Anne." So it stands to reason that if they use such intimacies in written letters, they would do the same in private conversations. There is a formalization of speech and manners that happened in the mid 18th century that was not as pervasive in earlier centuries-SC]. Ultimately, in my opinion, this comes down to an accuracy vs authenticity kind of question. I think writers of historical fiction should try their best to be as reasonably accurate as possible, but ultimately their focus should be on telling the best story possible, without jarring the reader.  Among the many things I never expected when I began to publish my historical mysteries is the steady stream of questions I get from readers. I really enjoy getting these questions, but sometimes I'm a little perplexed. The "easy" questions focus on interesting historical details, like how people kept time in the 17th century or what the revolving signet ring described in From the Charred Remains actually looked like. Sometimes they focus on larger questions, such as the gendered nature of the printing industry, the so-called "miracle" of the Great Fire, and the like. Sometimes, I just answer these history-related questions in a quick email, but I will probably start answering them in more detail on this blog. However, what's interesting to me is the number of questions that I'm starting to get about the decision-making processes that accompany the writing of a novel, especially historical fiction. "How do I decide on a time period/setting for my novel?" "How do I begin my research?" "How much research do I need to do?" "How much historical detail is enough?" "Do I need footnotes?" I hate to say it, but all of these questions can be answered in a single phrase. It depends. I know, I know. That's not very helpful. Since I've written at length in Writers Digest about seven tips for writing historical fiction,"Balancing accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction," I won't go into detail about those writing strategies here. And really, I don't have any particular insights about how to select an interesting time period. Choose a time period that fascinates you, intrigues you, keeps you enthralled. Keep in mind: this time period had better hold your attention, since writing a novel takes a very long time indeed! If you become bored with the time period, I have no doubt it will show in your writing, and your reader will become bored too. Truly, to answer such questions: "Have I done enough research?" "Have I offered enough historical detail?" "Do I need footnotes?" it really does depend on who your intended audience is, the kind of book you are writing, and the conventions of the genre. To answer these questions, there's a bigger question that you really need to ask yourself first: Am I actually writing historical fiction? This seems like a simple question, but I've been quite surprised when readers and writers ask me about the difference between history and historical fiction. It's clear to me now that there is a spectrum of categories, associated with the writing of history. None is "better" than another--each has a different purpose. I thought I would lay out how I conceptualize the difference in these categories: (1) Scholarly historical writing: This type of non-fiction writing is usually conducted by scholars and academics, produced in institutions of higher learning, museums and libraries, with highly specialized audiences and very small print runs with academic presses. Historical narratives and interpretations are framed by theory, historiography, with a strict adherence to evidence found in primary and secondary sources. Footnotes are crucial for credibility. Usually peer reviewed by other scholars/specialists before proceeding to publication. (2)Popular historical writing: This non-fiction writing may be very similar in scholarship to academic writing, but it may be more sensational in nature; it may be mass produced by commercial presses and readily found in bookstores; less emphasis may be placed on historiography and theory, but these features may still be present. Standards of evidence may be less strict. May not be peer reviewed, or only reviewed by editors. Generally, the writing seems more accessible and is intended for a lay audience. Footnotes are present, but are used more to explain ideas than to provide citations for every piece of evidence (again, this varies by publisher). (3) Fictionalized History: This is a tricky category to explain, because I think it is usually lumped together with historical fiction. I think this occurs when a writer takes a well-known historical narrative and adds to this narrative with made-up conversations and interactions between real historical figures. There is a great deal more supposition and creative license in constructing this type of narrative. Evidence may be selectively used to frame the overall story. Footnotes may be expected by readers. I think it is safe to say that this category can be called "Based on a True Story." (4) Historical fiction: While this varies, I would say that in this category, the historical narrative usually forms a backdrop to the story, with characters interacting with authentic details. Background theory and research will inform the best writing in this category, but will be implicit, not explicit. Historical fiction is not usually produced by academic presses, and undergoes editorial, not peer, review prior to publication. Much of the main plot may be fictionalized, even if there are real characters and true historic events being described. So in my case, the 17th century plague and the Great Fire of London form the backdrop of my stories, and my completely fictional characters sell murder ballads, spend time in Newgate prison, and scrub chamberpots. I do not have footnotes (ack! ack! not in a novel! Convention right now, at least in traditional publishing, is to eschew footnotes), but I do have a lengthy historical note in each book to explain historical points more or to indicate where I stretched the facts slightly to enhance the storytelling. I avoid information dumps, and try to get my characters to engage with the historical details. I'm telling a story, not writing a textbook. In any one of the above-mentioned categories, however, writers may be seeking to shed light on a little known historical event or figure, to expose larger truths, to offer new explanations and interpretations about a historical event or idea, or simply to provoke curiosity about a bygone era. One category is not BETTER than another; there are different purposes for each (and there are examples of good and poor writing in every category.) Ultimately, the level of historical detail and the length of the book will depend upon your intended audience (children, adults, scholars, history enthusiasts etc), the opinion of your editor and publisher, the conventions of your genre, and most importantly, the story you are trying to tell. But what do you think? Do these categories make sense?  Cosimo I de Medici, by San Friano, ca 1560 Cosimo I de Medici, by San Friano, ca 1560 It's fun answering reader questions! Keep 'em coming! Steve asked me, "In your books, Adam Hargrave, the magistrate's son, carries a pocket-watch. Did they really have pocket-watches back in the seventeenth-century?" Actually by the 1660s, pocket-watches were a fairly common luxury item among the middling and upper classes, so I thought it would be in character for Adam to own one. Pocket-watches had been around for a hundred years by this point, as illustrated in this image of Cosimo I de Medici, Duke of Florence, holding a golden timepiece. This painting represents the first known artistic depiction of a pocket-watch.  Samuel Betts, London, 1650 http://vergefusee.com/watches-and-movements-by-century/17th-century-2/ Samuel Betts, London, 1650 http://vergefusee.com/watches-and-movements-by-century/17th-century-2/ Initially, throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, nobles and other elites wore them either around their necks as pendants, or pinned to their clothes or attached to chains so that they could be placed in a pocket. The earliest of these simple watches seem to have had only a single hour hand, and they were not encased in glass, although they often had a protective cover of some sort. As the mechanics of time improved, watch-makers from England, France and the Netherlands began to offer more watches that were more elaborate, beautiful and accurate. They seem to have come in all different styles. The English ones were more simple, while the European models were often far more elaborate. Indeed, there are some really interesting pocket-watches...check them out! Tell me...Which is your favorite? (And here's a hint--one of them may be featured in an upcoming story...)  Recently, I have had a few questions from readers about one of the strange objects that Lucy had discovered on a corpse at the outset of From the Charred Remains. The item was a signet ring, one of several items found in a pouch on the body of a murdered man (check out what Lucy is holding on the cover). This ring, along with a hodgpodge of other eclectic items, will help identify the victim, as well as his killer. The signet ring I describe in the book was unusual because it swiveled to allow the wearer to display one of two different images.  Image: British Museum Image: British Museum I was immediately intrigued by the concept. I had come across this interesting ring style when I was prowling about on the British Museum's website. The ring featured here is from the early 17th century, and was made in either France or Germany. When you really think about it, what would be the reason to have a ring with two faces? Boredom? Perhaps. Cost? Unlikely, since a swivel ring might be very expensive to create. Or perhaps, there is something about who you are that you wish at times to keep private, and other times, make public. It is not surprising that certain organizations, like the Freemasons, have used such rings since the early modern era. This particular ring was probably more ornamental than practical, but I liked the idea that there could be a secret hidden beneath its surface.  In this image, you can see how the ring swivels, from an onyx intaglio of the Greek god Apollo to a sardonyx intaglio of a male and female figure (the website suggests it is likely Bacchus and Ariadne). This ring is a little more elaborate than I was envisioning though. Not, perhaps, as simple as these more simple masonic rings (a style also found in the 17th century), but somewhere in between. Pretty cool, hey? Makes you wonder why the wearer might commission a ring like this...doesn't it?

|

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed