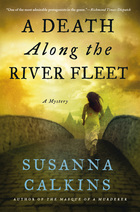

Dorothy Sayers Dorothy Sayers Recently* I came across the Detective’s Oath, written by Dorothy Sayers and first administered by G.K. Chesterton, as part of the initiation ceremony for the British Detective Club. The club, created in 1930, included the likes of Sayers, Agatha Christie, and a slew of other Golden Age mystery writers. The oath was this: “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?” While I think we’ve all seen authors—well-known ones at that—break these principles regularly (after all, why can’t a ghost solve a crime? Or for that matter, a cat?), there was something to these expectations that made sense. A reader should be able to work out whodunit, at least after the fact, to be fair.  But when I first read the oath, I had to laugh. I have situated my mysteries in early modern England, a time when divine revelation, providence, acts of God (or the Devil, for that matter) often served as the explanation for most mishaps and misfortune. It would have been so easy—and realistic—to have my sleuth solve crimes in that fashion. After all, there are many incidences of a community “solving” a murder when a corpse’s finger pointed to its murderer. Or when the corpse’s eyes would open and stare in the direction of the murderer’s house. There are even examples of a corpse bleeding from the nose or ears, indicating that the murderer was in the vicinity. Sometimes, logic and reason and evidence would prevail and sometimes…they did not. There are many examples of superstitions, hearsay, and feelings making their way into court testimony, especially in ecclesiastical courts.  Certainly in A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, when a young woman is found dazed and confused with blood on her clothes, there is immediate suspicion that she might be bewitched. But I wanted Lucy Campion, my chambermaid turned printer's apprentice, to be someone who was resourceful and intelligent, despite having little formal education. But it wasn’t just about creating a character who would use her wits and evidence to solve crimes; I wanted her to question how the community identified murderers in the first place. I also wanted Lucy to be someone who rejects the notion of providence as a means to explain murder. I wanted her to dismiss the idea that divine revelation could be a reliable way to identify a murderer—even if that meant challenging the expectations of her community. I’d like to think that Lucy would approve of the Detective’s Oath. This post was first published on the Bloody Good Read.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed