|

It seems like every day I receive a Google Alert, kindly informing me that another site has popped up, allowing my books to be downloaded for free. Not only are these parasitic companies stealing from me and other authors, but to add insult to injury, many users actually post comments on these sites, thanking these bottom-dwellers for the "service" they provide to readers. Sometimes these comments are so heartfelt it makes me wonder if the users don't realize they are committing an actual crime. Is that possible? Taking a step away from my indignant high horse for a moment, I do find it interesting that plagiarism and piracy of books has been around since the invention of the printing press. Initially, imitation in the Renaissance was seen as a compliment, a form of flattery, at least in art. In the world of the cheaply printed piece, necessity and practicality were at the heart of imitation. Printers regularly used the same woodcut again and again--say, of someone being hanged--most likely for ease of use and to evoke a certain image or memory in the audience. But over the next century or two, there seemed to be growing concern with the ability of printers to simply reset a piece and sell it for themselves. On occasion, advertisements to booksellers were created, informing them when a "sham" edition of a book had been created. They would implore the bookseller to consider the nature of property; they also seemed to speak to the bookseller's sense of quality, by reminding them of the inferiority of the sham piece. For example, this next advertisement reminds the bookseller that "The sham edition has several mistakes and blunders, contrary both to sense and grammar." Some of these advertisements even specified that the printer, publishers and dealers would be prosecuted by the Company of Stationers, who as a royal guild had the sole power to oversee the publication of most written work, including almanacks as described in this next advertisement. In particular, I like the last line, which warns against those who would claim not to have known they were doing anything illicit: "This notice is given to prevent all persons from coming into trouble through ignorance." Lastly, I suspect this is where the practice of authors signing their own books came from--the author was attesting to the authenticity of his (or possibly, her) books. I don't know if its particularly heartening to realize that piracy and plagiarism are not a new phenomenon for authors. But it is interesting to think that such acts had long been condemned by the publishing community, even if the problem is still present 200 years later.

In my next post, I will tell you what happened to one of these plagiarists...

3 Comments

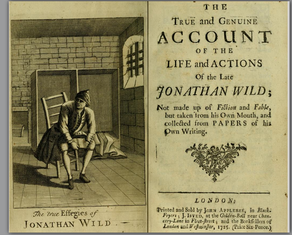

Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  Betsy Ross, 1777 (Ferris, ca 1920) Growing up in Philadelphia, I was both immersed in and oblivious to the colonial history that surrounded me. After school my friends and I often went to the mall by the Liberty Bell or we hung out in beautiful Independence Square, within a few yards of where the Declaration of Independence was signed, rarely heeding the significance of our historic surroundings. I admit, sometimes we'd laugh at the tourists snapping countless pictures, reading signs, peering at maps, buying outrageously expensive soft pretzels (everyone knew you don't buy them in the tourist areas!), pitching pennies on Ben Franklin's grave (years later, I understood why they did that--they were paying homage to the man who coined the phrase in his Poor Richard's Almanac, "A penny saved is a penny earned"--but at the time we thought it was a pretty silly thing to do.) Hey, we were kids. But I'm sure if someone had asked, we'd have been able to give a decent enough explanation of the events leading to the break with Great Britain, maybe something about John Hancock and Thomas Jefferson, etc. Heck, I'm sure we could have offered up the great tale of how Betsy Ross was asked by none other than George Washington himself to create the first American flag. And how that flag she sewed, with its unique star pattern, helped inspire a burgeoning nation to independence and unity. Or something along those lines. You don't mess with Betsy Ross. But as a historian now, I look back and question how history and legend became intertwined with our local popular memory and national identity. Only a little digging reveals that few vexillogists (people who collect and study flags, and also my new favorite word) and historians agree with the popular conviction that Philadelphia seamstress Elisabeth Griscom Ross (a.k.a. Betsy Ross, revered national icon) actually made that first flag (let alone that General Washington commissioned it). Indeed, the evidence appears to be scant one way or the other, and heavily anecdotal in nature. Much of the sentimental legend appears to have derived from a popular account put forth by Ross's daughter, and related in full by her grandson, in the late nineteenth century. Even then, however, scholars seemed a bit skeptical about the veracity of the legend, but the romantic quality seems to have captured the imagination of Ross's biographers, and the legend somehow became true. (Noted historian Laurel Ulrich offers an excellent discussion of how this transpired, and why Betsy Ross is still an important figure in U.S. history).  Another vexillogy related point (and yes, I am hoping to use that word repeatedly)--is the so-called "Betsy Ross five-pointed star pattern." Again, all kinds of myths abound about the origins of this type of star: some argue that the stars were connected to George Washington's family crest (doubtful, despite the red stars on the crest, given that this was the same man who would not be king); or perhaps to European heraldry (maybe some influences here), or most likely to the early naval signs. Say what you will--my money is on the alleged connection of the early founding fathers to the Masonic order (supposedly stars were one of their symbols, along with pyramids etc. The Da Vinci Code in America, anyone?) Even though legends about Betsy Ross and the flag are enjoyable, I think it's important to consider their origins. But what do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed