credit: http://johnaconnell.com/ credit: http://johnaconnell.com/ The Brothers Grimm meet the Nazis? I'm delighted to have John A. Connell join me on my blog today. Here, he describes how a small city in Germany served as the dramatic backdrop for SPOILS OF VICTORY, his latest crime thriller set during the post-World War II era. The dark layered history of this small city is truly fascinating...  Garmisch-Partenkirchen Garmisch-Partenkirchen Garmisch-Partenkirchen would seem like an unlikely place to set SPOILS OF VICTORY, my latest crime thriller about murder and organized crime in post-WW2 Germany. The small German city—or large town, depending on how you look at it—could have been the setting for a fairytale in some far-off land. Nestled in a valley of the Bavarian Alps, its streets are graced with Hansel-and-Gretel houses and buildings with frescoes of pastoral scenes or local saints. Partenkirchen, first mentioned in 15A.D., was originally a Roman settlement, and one of its main streets still follows the old Roman trade route between Venice and Augsburg. Garmisch was settled 800 years later by a Germanic tribe. Separated by the glacier-fed Partnach river, the two towns remained separate until Hitler forced them to unite in 1935. Garmisch (as it is commonly called—much to the chagrin of the people of Partenkirchen) has been a favored winter resort since the late 1800s. The highest mountain in Germany is there, and the entire region is crisscrossed by world-famous ski slopes and dotted with placid alpine lakes. Hardly a promising location for murder and mayhem.  Werdenfels Castle...haunted? Werdenfels Castle...haunted? On the surface, that is, as Garmisch-Partenkirchen has had several dark periods. The first came in the 1600s, when the importance of overland trade routes dried up, causing Garmisch-Partenkirchen to come to near ruin. Privation, plagues, and crops failures led to witch-hunts, and in one two-year period 10% of the meager population was burned at the stake or garroted. Legend has it that Werdenfels castle, where the “witches” were imprisoned and executed, was so haunted that it was abandoned and torn down to build a church to drive away the evil that lurked within its walls. An even darker period descended on Garmisch with the Nazis’ rise to power. Göring went there to be treated for a bullet wound after Hitler’s failed putsch and given honorary citizen status by the city’s leaders. Hitler had wanted to buy farmland there for his mountain retreat, but the farmer wouldn’t sell, and Adolf ended up building his Eagle’s Nest in Berchtesgaden; a veritable who’s who of Nazis had called Garmisch their home away from home. The vestiges of the 1936 Winter Olympics still stand as monuments to Hitler’s dream of a 1000-year empire, though gone are the Nazi banners and signs forbidding Jews, or the elite Gebirgsjäger soldiers and swastika flag-waving fanatics. Indeed, it was a past so sordid that the town only commissioned it's archives in 1972—the people had no interest in remembering their Nazi past.  German soldiers of the Hermann Göring Division posing in front of Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1944 German soldiers of the Hermann Göring Division posing in front of Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1944 So, why did I decide on Garmisch-Partenkirchen for murder and mayhem? It was really by serendipity. My protagonist, Mason Collins, was actually the villain in a previous, defunct novel, with him committing murder in order to steal a cache of Nazi gold in occupied Germany. It was when I began researching Mason’s murderous backstory that I discovered that after WW2 the charming and beautiful Garmisch-Partenkirchen had become the Dodge City of occupied Germany! When the Third Reich collapsed, and the Allied armies were pushing into Germany from the west and east, Garmisch-Partenkirchen became the stem of the funnel for fleeing wealthy Germans, Nazi government officials and war criminals, retreating SS, and former French Vichy and Mussolini officials. And for the same reason it also became the final destination for Nazi-stolen art masterpieces, vast reserves of the Third Reich gold, currencies, precious gems, penicillin, diamonds, uranium from the failed atomic bomb experiments. After the war, all that became available for purchase on the black market. With millions of dollars to be made, murder, extortion, bribes and corruption became the norm. The promise of fortunes also brought in a multitude of scoundrels, scam artists, and gangsters. Add to this, tens of thousands of bored US Army soldiers ripe for temptation. The black market thrived, and gangs of deserted allied soldiers, former POWs, ex-Nazis, and corrupt displaced persons roamed the countryside. With the U.S. officials looking the other way or profiting from the activity, some gangs operated so openly that they were more like import-export companies. Here was this fantastic contrast: a Brothers Grimm fairytale town behind whose charming facades lurked mayhem and murder. It is said that truth is stranger than fiction, and, in this case, it has proved true. I even left some of the crazier stories out just to make seem more “real!” So, as it turns out, Garmisch-Partenkirchen was a great setting for a historical crime thriller after all!  From the official blurb: From the author of Ruins of War comes an electrifying novel featuring U.S. Army criminal investigator Mason Collins, set in the chaos of post-World War II Germany. When the Third Reich collapsed, the small town Garmisch-Partenkirchen became the home of fleeing war criminals, making it the final depository for the Nazis’ stolen riches. There are fortunes to be made on the black market. Murder, extortion, and corruption have become the norm. It’s a perfect storm for a criminal investigator like Mason Collins, who must investigate a shadowy labyrinth of co-conspirators including former SS and Gestapo officers, U.S. Army OSS officers, and liberated Polish POWs. As both witnesses and evidence begin disappearing, it becomes obvious that someone on high is pulling strings to stifle the investigation—and that Mason must feel his way in the darkness if he is going to find out who in town has the most to gain—and the most to lose…  John A. Connell is the author of Ruins of War and SPOILS OF VICTORY, the first two books in the Mason Collins series. He was born in Atlanta, where he earned a BA in Anthropology, and has been a jazz pianist, a stock boy in a brassiere factory, a machinist, repairer of newspaper racks, and a printing-press operator. He has worked as a cameraman on films such as Jurassic Park and Thelma & Louise and on TV shows including The Practice and NYPD Blue. He now lives with his wife in Madrid, Spain, where he is at work on his third Mason Collins novel. Visit him online at johnconnellauthor.com.

1 Comment

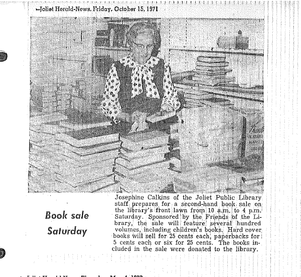

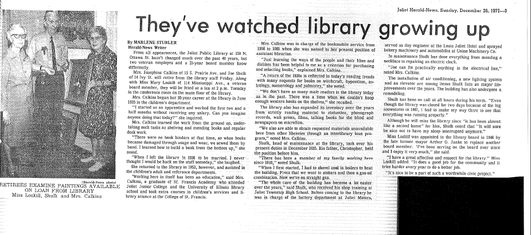

Given that My Fair Lady is one of my favorite musicals, I was quite intrigued when I learned that D.E. Ireland had transformed the unlikely uncouple--the curmudgeonly linguistics professor Henry Higgins and the charming but inarticulate Covent Garden flower-girl--into a crime-solving duo. Loverly! I am thrilled that the two authors who comprise D.E. Ireland were able to waltz their way over to my blog today, and answer some questions about their debut novel and the writing process.  From the official blurb: Following her successful appearance at an Embassy Ball—where Eliza Doolittle won Professor Henry Higgins’ bet that he could pass off a Cockney flower girl as a duchess—Eliza becomes an assistant to his chief rival Emil Nepommuck. After Nepommuck publicly takes credit for transforming Eliza into a lady, an enraged Higgins submits proof to a London newspaper that Nepommuck is a fraud. When Nepommuck is found with a dagger in his back, Henry Higgins becomes Scotland Yard’s prime suspect...  D.E. Ireland researching high tea D.E. Ireland researching high tea SC: I know that the two of you became friends when you were undergraduates, but how did you become “D.E. Ireland?” Can you tell us a little bit about how you decided on the name? Does it mean something? DEI: We are longtime friends and critique partners and have been looking for an idea to collaborate on for years. And voila, while singing to the My Fair Lady soundtrack on her way to visit Sharon a few years back, Meg stumbled on putting Eliza and Higgins together as amateur sleuths. We plotted, outlined, then wrote the first book in the series. Since we're both published authors under our own names, we needed to choose a pseudonym. We finally agreed upon ‘Ireland’ in honor of George Bernard Shaw who was born in Dublin. And ‘D.E.’ is Eliza Doolittle backwards! SC: Your mystery features the unlikely yet beloved couple from stage and screen, Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins, from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (later adapted as My Fair Lady.) What was it about these characters—a guttersnipe from the dredges of London, and a professor of linguistics—that appealed to you as amateur crime-solvers? DEI: We are both huge fans of the play and the movies. Since Shaw's Pygmalion is in the public domain, we used his play and the delightful banter between Eliza and Higgins as the models for our own series' characters. However we had to flesh out their backgrounds along with that of the other characters such as Pickering, Mrs. Pearce, Mrs. Higgins and the Eynsford Hill family. In the play, Eliza worked hard to win Higgins's bet, yet she hadn't truly earned – and kept! – his respect until our series. We want to keep alive the witty exchanges these two whip at each other, and continue to expand on their friendship as they turn their collective talents to sleuthing. That should be great fun. SC: The book offers a great deal of detail about life in Edwardian London (1913). How did you conduct your research into this era? What was the most interesting or surprising thing you learned while conducting your research? DEI: We are both research hounds; Sharon wrote several historical romances set in the Old West and Victorian England, while Meg has written American western mysteries. Sharon was also a college history instructor so the opportunity to research Edwardian England seemed like great fun. We eagerly started digging into the era immediately following the death of King Edward VII. We love the two PBS series Downton Abbey and Mr. Selfridge, and both shows serve as inspiration. But we rely heavily on our "Edwardian Bible" which we have compiled that includes London shops, streets, parks, neighborhoods, food, social behavior, etc. And of course, we always refer to Shaw's Pygmalion, along with his appendices and notes of the play which include descriptions of Higgins' phonetics lab and his mother's Chelsea flat. Book 2 required that we expand our research to include horse racing, Ascot, the Henley Regatta, along with the suffragette movement. The most interesting or surprising thing? Hmm. Since electricity, autos, the telephone, and the cinema had shown up by the 1900s, perhaps it was our realization at how similar life was then to our times now -- except for fashion and manners of course. SC: Do you foresee Henry Higgins developing over time? Will he be out petitioning for votes for women in future novels? DEI: Oh, we think Higgins is the one who will be clinging to his fencepost, kicking and screaming for the old days. Eliza is the changeling of the pair and will tug and pull him into the 20th century!  A while back, I was contacted about participating in a local author fair. Not only was I just personally delighted, given how much I love libraries and librarians, but I was just amazed when I saw who had extended this very kind invitation. The Joliet Public Library, Black Road Branch. In Joliet, Illinois. Now before I came to live outside Chicago, I grew up in Philadelphia. My father, however, had grown up in Joliet Illinois. His mother, my grandmother, worked at the main branch of the Joliet Public Library for thirty years, retiring shortly after I was born in 1971. In an interview published in the Joliet Herald-News dated December 26, 1971, my grandmother explained that she'd started as an apprentice at the library, working her first two and a half months without pay! Initially, she mainly shelved books, but was also called on to mend books as well: "There were no book binders at that time, so when books became damaged by usage and wear, we sewed them by hand. I learned how to build a book from the bottom up."-Josephine Calkins  My grandmother, 2 weeks before I was born! My grandmother, 2 weeks before I was born! She left the library in 1936 to get married--my father says she met his father at the library! After taking coursework at the University of Illinois library school, she returned to the Joliet library in 1953, working in the children's, reference, and adult departments. From 1956 to 1965, my grandmother was in charge of the library's bookmobile, before becoming an assistant librarian. The experience at the bookmobile, she said, helped her learn about what people liked and disliked, which later informed her purchasing decisions.  When asked to reflect, in December 1971, about what had changed since she first started working at the library, she had this to say: "A return of the 1930s is reflected in today's reading trends with many requests for books on witchcraft, hypnotism, astrology, numerology and palmistry....We don't have as many male readers in the library today as in the past. There was a time when we couldn't keep enough western books on the shelves...." I can only imagine what my grandmother would think of current library trends now. Back then, microfiche and microfilm collections as well as "The New InterLibrary Loan Program" were just starting to transform how library patrons could access materials. What would she think of the digital revolution?

Unfortunately, my grandmother passed away in 1987, so we can't know. From what I do remember, she had a deep and abiding love of books, which she passed on to my father and my siblings. I'd imagine she'd be thrilled at the ready access of books and the long reach that modern libraries can attain. (The other thing I remember about my grandmother was that she taught me to embroider, on one long visit to Philadelphia. While I appreciate that skill, I can't help but wish now she had also taught me how to build a book--a worthy skill indeed!) As I've mentioned before, I grew up in a house literally lined with books, many of them bequeathed to us from my grandmother. I truly believe that my love of writing stems from my love of reading, a trait inherited from both my parents (my mother was also a librarian). So I believe it will be quite a moment when I set up my table on Saturday. On one side, my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. On the other side, the photos of my grandmother passing out books at the Joliet bookmobile. My parents are even making the trek out! I don't know what to expect exactly, but I'm sure it will be great!  Two hands good, one typewriter bad In college, I took a really great class on George Orwell. While I enjoyed exploring his better known works (such as Animal Farm and 1984), I was fascinated by the essays that Orwell penned about different aspects of his life. In particular, Orwell's essay "Why I Write" resonated with me at a deep level. I read the piece again recently, and I'm still struck by his explanation of what motivated him as writer and--arguably--perhaps all writers. He says there are four main motives for writing:

These last two points do much to drive and inform my own historical novels. I don't believe in absolute truth, or in one set historical narrative. I do hope, however, to get readers to question their perceptions of society, culture, gender, power and privilege--to rethink what they think they know. While my agenda is wrapped up in what I hope is a compelling mystery, its certainly there. I'm curious though. Do you agree with Orwell? Are books by nature political, in the widest sense of the term? Harry Potter? Twilight? The Lord of the Rings?  The wall through Qalquilya The wall through Qalquilya The first time I read Faulkner's As I Lay Dying I was fascinated by the fifteen or so perspectives on the same event: the death of Addie, the sickly matriarch of a poor Southern family. There's a challenge, however, to acknowledging multiple perspectives of an event, to recognizing the value of competing narratives, even when multiple points of view can do much to advance a story. Recently, I've been thinking a lot about competing narratives, as I've traveled throughout Palestine and Israel as part of a higher education-related initiative I've been involved with through my "day" job. Last year, on my first trip to this highly-fraught region, my team was invited by several of our new colleagues--professors from a large Palestinian university-- to visit their communities. We found their families and neighbors to be warm, friendly--and extremely welcoming to strangers who could barely speak ten words of Arabic altogether. On one occasion, we visited Qalquilya, one of the communities divided by the Wall ("security fence"), and a town at the forefront of the troubles in the West Bank. Designed to separate the Palestinians in the West Bank from the rest of Israel, the Wall certainly now stands as a palpable symbol of the overwhelming distrust, fear, anger and sadness that has kept these peoples apart. Our colleague showed us around this town where she'd grown up, pointing out the small plot of land where her family still managed to grow vegetables. Under the hot sun, we sat beside the Wall, sipping mint lemonade, watching her neighbors shear sheep and her little niece kick a ball among the trash and compost. I remember this little girl asking me "What was it like, beyond the Wall?" As a Palestinian, she had no ready means for a visa that would allow her to see what was beyond the Wall for herself. Last week, on my follow-up visit, my group was able to take a trip to Haifa-- a city on the Mediterranean decidedly not within the West Bank. (The irony of being a foreigner--we could travel anywhere we wanted). Along the way, as we drove along the well-maintained Israeli highway, many tour buses passed us. I could see the tourists inside taking pictures of the Wall which, from our current vantage point, looked exactly like the walls you might see around a maximum security prison. I have no doubt the Wall looked scary and ominous. (Indeed, I met an American on the plane ride home who whispered to me how he had seen the Wall, with the air of someone who had braved something unimaginable.) The next moment, though, our tour guide mentioned that we had just passed Qalquilya--I was shocked. And profoundly disturbed. We could see the Wall, but nothing of the humanity within. Somewhere in there, my colleagues' little niece was playing. Or maybe she was staring at the Wall, still wondering who was out there, and why she was locked inside. I won't pretend to understand the complexities of Israeli-Palestinian relations. But clearly, there is more than one "true" narrative. I believe that writers of all types, whether of fiction or non-fiction, would do well to consider an event from more than one perspective. Few writers wield Faulkner's skill of course, to imagine the same event from 15 separate angles. And I'm not sure I've been brave enough to try. But questioning what is known, questioning one's beliefs, and seeking different takes on a subject, is crucial--for writers, and certainly for critically-thinking human beings. What do you think? Have you seen instances where using multiple perspectives has worked well? How?  Entrenched in intrigue I'm always fascinated by the way words seep into the English language. In honor of my Downton Abbey withdrawal and Florence Green (the last World War I veteran who passed away a few weeks ago at 111) AND because I recently wrapped up a class discussion on the Great War, I thought I'd say something about how WWI introduced some rather evocative--if heartbreaking--language into our vocabulary.  fashion from the trenches In 1914, Burberry was commissioned to create a new type of coat, the trench coat, that would allow British officers to stay both stylish and comfortable during the war (not sure how that worked out...) After the war, the coat became extremely popular, made even more so when it made its way to Hollywood. (Nowadays, the trench coat is so pervasive, I always wonder if anyone thinks twice about its origins.) Lots of phrases are still around, too, mostly from the terrible conditions soldiers had to face. "In a funk" (feeling dejected) may have referred to the (funky/smelly) holes in the trench walls where soldiers could stand to keep dry."Lousy" referred first to lice infested clothes, later to everything crummy. "Dig oneself in" (stick to one's ground, being stubborn) came from entrenching. To be "Up against the wall" (in a difficult spot) probably came from deserters' placed in front of a firing squad. (All a bit stomach-churning, really). Shell-shock--a kind of obvious one. And sadly, "basket case," a term for someone who's a bit screwed up, arose from the practice of transporting severely injured men in baskets.  Snoopy stayed out of the trenches Some, of course, came from the early aviation: "In a tail-spin," "joystick," "nose dive" --all essentially descriptive. "Hush-Hush" referred to top secret operations. And a "dud" (a failure) comes from an unexploded mine or shell. And of course, the very best. Snoopy, the World War I flying "Ace." An excellent pilot, he was the high card to play against the dreaded Red Baron. (Although, now, when I see Snoopy reenact the prolonged suffering of a lonely airman stationed in France, I find it quite disturbing.) What other vestiges from the Great War do we still speak and hear daily? You tell me! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed