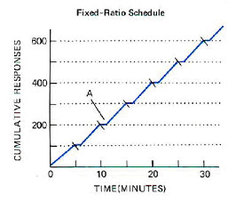

What's he waiting for? What's he waiting for? A few weeks ago, I received my editor's notes for A Death Along the River Fleet. As always, the comments were insightful and thorough, but not particularly hard to address or to think through. And yet I found myself wanting to do anything but sit down and work on them. Everything else was suddenly more immediate, more necessary--organizing a desk drawer, writing a blog post (including this one), and a vast array of other far less important things and activities. Classic procrastination, right?  http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg But why? Why would I procrastinate on a task that I knew I wouldn't mind doing--that I might even enjoy doing? I mean, usually when I procrastinate, its because there's a task looming that I really don't want to do. Like, cleaning the litter box. Pulling weeds in the garden. Other tedious or annoying tasks like that. So why was I putting off a task that I didn't really mind doing? If it's not procrastination, is it simple weariness? Or maybe fatigue? But I didn't really feel exhausted. I mentioned this question to my husband--my alpha reader and in-house cognitive psychologist--because he can offer a psychological explanation for anything that plagues me as a writer (e.g. Me: "Why can't I remember what happens in my books?" Him: "You're not crazy, you're just experiencing proactive interference.") So in this case, he told me that my most recent issue was probably not truly procrastination, but rather something called a "Schedule of Reinforcement." So the schedule of reinforcement goes something like this: Imagine that an adorable little rat with a bright twitching nose is in a box with a lever. That rat is on a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, which just means it will receive a food pellet (reward) after every 100 lever presses. Once the rat begins to press the lever, it will work at a fast steady pace until the food reward is earned (the up slope in the figure below). (So if I'm the rat in this scenario, I've earned my reward--I've sent my book in to my editor and received my edits.) However, once the rat earns the reward, it stops responding for a while (the flat point A in the figure). This is known as either the “post-reinforcement pause” or the “pre-ratio pause.” Essentially, the length of the pause is proportional to the amount of work that was required to get to the reward. The interesting part, he explains, is that, generally, the length of the pause is not due to fatigue. Instead, the rat--or other organism, like a human being--seems to use that time to mentally prepare for the large amount of work to come. He says it’s not fatigue because if you artificially get the organism to begin (e.g., place rat paws on lever so that it depresses), then the organism will go on a “ratio run” and perform the behavior until the next reward is given (even if it just completed a run and had no break). So apparently, this has interesting implications for procrastination with humans. As he explains, research on schedules of reinforcement suggest that the best way for a human to overcome procrastination is to artificially get the human to begin the project. For instance, if a college student has to write a term paper, s/he can trick themselves by saying, “I’m only going to write the first two sentences and then I’ll stop.” Often, once they begin, they go on a “ratio run” and write much more than intended (just like when the rat was forced to depress the lever). So, the takeaway for writers (because this is apparently what happened to me): "When you have to dig back into a project (e.g., edits), it’s probably not fatigue that leads to procrastination. That “procrastination time” is used to mentally gear up for the considerable amount of work to come. Even so, simply starting (e.g., on the easy edits), can lead to a ratio run and solid progress." So a scientific explanation for what we all at heart know is the secret for overcoming procrastination: Get your butt in chair and JUST START....but start with the easiest thing possible. The rest will come. And hey, let me know if you have any other writerly conundrums that you would like a professional psychologist to explain. He can come up with a theory for anything. Just address your query to "Dear Alpha Reader." :-)

6 Comments

Bon-Bon Seller, 1838 (British Library) Bon-Bon Seller, 1838 (British Library) It's a Saturday. I'm taking a few hours to finish the revisions on my third Lucy book. I carefully negotiated this time with my husband (aka the Alpha Reader), which of course was more like, "Ohmygod, Ohmygod, Ohmygod....I gotta get these revisions finished because I need to get the copy edits and we need some ARCs and I need to finish the fourth book which is due in April and what was I thinking working on a side Young Adult novel which has not been contracted and I need to write some blog posts and won't the kids be upset that I'm not spending much time with them this weekend and I wonder how that book club I did last night went and don't I have a few more events coming up when are they anyway and I think there's some day job stuff I need to finish up and ohmygod etc etc" I usually do most of my writing at night, when the kids are in bed, but when deadlines loom, I need to carve out extra time in my schedule. And of course my dear Alpha Reader just held up his hand and said, "Don't worry. Take a few hours today." Seriously. Best. Husband. Ever. So off to my coffee shop I went to work--mostly guilt-free--to work on these book three edits. But I wasn't here too long before someone I knew from the neighborhood stopped by to say hello. Seeing my 350 pages of manuscript strewn about the table, my laptop open, the remnants of my morning bun (which I really wish I hadn't succumbed too) and my mostly chugged non-fat latte, she said to me, "I wish I had time to sit around writing a book." Although her tone was dismissive, or perhaps envious, she is a lovely woman, so I think I just smiled politely and said "Well, I think its about carving out time and--" But she just shook her head. "I just don't have that kind of free time to just sit around and write," she repeated and walked away. The implication was clear. Writing is a leisure activity, like laying out at the pool. But if she had just had the time to do it, she'd easily knock out a best-seller. So what I didn't say, but which I wish I had, is this: It's not really about the time. It's about the will. It's about the drive. It's about the focus. Obviously, you need time to complete a novel, but all the time in the world won't help you write if you have no will or drive. If writing were just about "finding free time," I'd feed you the bonbons* myself. Real writers write.** They don't just think "I've got a great idea that will become a best-seller just as soon as I take a few weekends off from my busy schedule." They carve out the time, by hook or by crook, and they sit in their chairs, with their pads of paper or at their keyboards, and they WRITE THE FRIGGING STORY! [**As much as I wanted to end with a pithy closure, I just want to acknowledge that I completely understand that some writers have true and very real constraints upon them. Not everyone has an Alpha Reader who can help them carve out the time they need. But I don't put those writers in the bon-bon sun-tanning leisure crowd of wannabe best-selling authors. To those writers I say, Try to keep at it. A page here, a scene there, and eventually the book will be done! My first novel took me ten years to write!] [**I don't think I've ever had a bon-bon, but now its on my list of things to try] So the question I have is this: What kind of writer are you?  the lovely Lisa Alber the lovely Lisa Alber In 2001, I traveled to County Clare, Ireland with my new husband (aka alpha reader and my chief psychological consultant) on our honeymoon. I remember we were struck by the beauty--and moodiness--of the land. I'm delighted to be joined today by Lisa Alber, who perfectly captures this sense of mystery and longing in her debut novel, KILMOON.  How beautiful is this cover? How beautiful is this cover? From the official blurb: Merrit Chase travels to Ireland to meet her father, a celebrated matchmaker, in hopes that she can mend her troubled past. Instead, her arrival triggers a rising tide of violence, and Merrit finds herself both suspect and victim, accomplice and pawn, in a manipulative game that began thirty years previously. When she discovers that the matchmaker’s treacherous past is at the heart of the chaos, she must decide how far she will go to save him from himself—and to get what she wants, a family. Lisa, thanks for joining us today. What inspired KILMOON? Two places in Lisdoonvarna village, County Clare, Ireland, sparked my imagination: The Matchmaker Bar and an early Christian ruin called Kilmoon Church. The Matchmaker Bar represents the village’s annual matchmaking festival and Kilmoon Church represents secrets long buried. Together they grounded me in place and set my thoughts churning about a matchmaker with a dark past. My dad’s death also inspired this story. I was grieving his passing (from cancer), and it was only later that I realized I was processing our relationship through the father-daughter themes that run through the novel. Of course, in the novel they’re far darker than anything from my life. Thank goodness! Your locale is very evocative—sometimes dreamy, sometimes harsh. How did you settle on County Clare for your location? Did you spend much time there? You might say I accidentally ended up in County Clare. I traveled to Clare for the first time to see an ecological area called The Burren, which is a vast area of limestone leftover from the Ice Age. I’d read about it in a memoir. I planted myself in a random B&B near The Burren—in Lisdoonvarna, as luck would have it. While there, I discovered that Lisdoon (as the locals sometimes call it) hosts an annual matchmaking festival. I visited the area three times for novel research. I found the landscape both harsh and dreamy. How interesting that these aspects of the locale came across to you in the novel! The Burren has a harsh appearance, that’s for sure, and the winds that come in off the Atlantic can be dismal. On the other hand, on mild days, the rolling green hills with their drystone walls are peaceful and otherworldly—like the landscape hasn’t changed in a thousand years.  I've been running into a funny problem while reflecting on the edits for my second Lucy Campion mystery (From the Charred Remains, out in April 2014!). It's the same problem I encountered when talking to a book group tonight... I'm having some trouble keeping the details of my stories straight. Crazy, right? How can I not know my own stories? I spent YEARS writing them (at least A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.) But still, I have notes and charts and timelines and figures (yes, figures!) detailing subplots, tracking character motivations, etc. And yet, I'm still a bit confused sometimes. How is this possible? So I raised the question of my faulty memory with my chief psychological consultant (literally my resident psychologist, a.k.a my alpha reader). "I wrote the darn thing!" I whined, er, lamented. "How can I not remember all these details? I shouldn't have to re-read my notes to know my own story. Do I just have the worst memory in the world?" And, with a lift of his eyebrow and a stroke to his goatee, my cognitive psychologist replied, "Ah, well let me tell you about a little thing we in the field like to call PROACTIVE INTERFERENCE." And here's what he explained: "I'd imagine it's always harder for the writer to remember the details than it is for a reader. For the reader, there is one reality and it is laid out there on the page. The writer, however, has vividly imagined (and discarded) many realities. These early imaginings compete and interfere with the memories for the most recent version of the story. This proactive interference is a hallmark of human memory and, sadly, it is largely unavoidable. Be thankful that you took good notes in the first place!" (See why I keep my alpha reader in my permanent employ? He helps me rationalize my disorderly thinking with a neat psychological construct!)

But this idea of proactive interference, and this notion of multiple imagined (and discarded) realities, really does resonate with me. I've found that even though I take notes as I write, I don't keep track of the scenes, characters events, etc. that get deleted or shuffled around. So I retain this memory of what I wrote, even though it's no longer in the manuscript, which is why I'm sometimes confused months later. I also wrote another unrelated novel in the interim, which probably doesn't help with my recall of the one currently being edited. Perhaps I could do a better job of documenting the changes I make when I write (although, really, it's not like I EVER get rid of a draft!). But, in a way, I sort of like the idea that underlies this confusion. Maybe it's part of the romantic image of writer as creator: the idea that one being can simultaneously hold multiple realities is strangely compelling. Or maybe its just convenient to pull out the "proactive interference" defense. Dazzle my questioners with the multiple realities angle, and I can sidestep the missing details altogether. But what do you think? Will that fly?  The alpha reader wolf This weekend, I'll be working on the first set of suggestions for my second novel, From the Charred Remains, compliments of my alpha reader (a.k.a my dear husband Matt). Even though I sometimes gnash my teeth and grimace over his comments ("Who cares if I start three sentences in a row with "And"? "What do I care what color this character's eyes are?"), I think he gives really good comprehensive feedback. So I asked him to offer his insights into what it's like to make suggestions on a novel in progress. (Disclaimer--he says some nice things in here about me, which I really didn't make him say). ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I’ll never forget the moment that I finished reading the very first draft of A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate. After years of knowing next to nothing about the novel, suddenly all had been revealed. (So true, I never told him I was writing a novel. --SC) I remember feeling many emotions, with pride and awe being the most salient. I recall thinking, “Wow, this feels like a novel that people buy from Barnes & Noble! How did she create this vivid world and these vibrant characters? How did she develop this compelling mystery that kept me guessing until the end? How did she weave such interesting historical details into story? Just wow.” Then came feelings of satisfaction and contentment—“What a great ending”—and a yearning for more—“I miss Lucy already. I wonder what will happen in the next book?!?” After sharing these thoughts with Susie, she reminded me that the other duty of the alpha reader is to provide constructive feedback. I remember feeling ill-equipped for this task. “Who am I to give a critique? I’ve never written a novel and I doubt that I ever could. What can I offer that would be of any value?” During my careful rereads of various drafts, I learned that I could provide some valuable feedback (e.g. "Why would this character do that?" "I thought you said it was raining outside," or "You know you said this character was dead--what is he doing talking to Lucy?"). Susie subsequently rewarded me with a variety of titles: Vice President of Continuity Management, Head of Repetition Detection, and Director of Necessity Questioning. Although these titles are simply meant for fun, I take great pride in them and I am thrilled that Susie asked me to continue in these roles for book two: From the Charred Remains! Having recently read the first draft of FTCR, I found myself filled again with awe and pride—“How did she do it again?”—and a yearning for more—“When will book three be ready?!?” Can you relate to any of these experiences? Feelings of pride and awe in the accomplishment of someone close to you? The tough position of providing constructive feedback? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed