|

Oh, yes! It's exactly what you think. Read on! Naturally, the subtitle says it all... “Giving An Account of an Old Miserable Woman, who lately kept a blind ale-house, in St. Tooley-Streat, near the Burrough of Southwark; who was so wretchedly covetous, as to deny her self the common benefits of life, as to meat and cloaths; leaving, at her death, about fifteen hundred pounds, to her cat, using to say often, when the cat mow’d: “Peace Puss, peace: The poem that ensues is a bit silly but sort of endearing as well. (And I have to say, it was nice to see a relationship between a woman and her cat that was not wrapped in accusations of witchcraft, bestiality or other fantastical conjectures.) As the story goes, for years, this "mean" woman did not spend her money, preferring to keep her alehouse earnings to herself. Finally, when no one had seen her for a while, one of her neighbors went in to check on her: “Upstairs he went, and in the bed, He found the Rich Old Woman dead: And, looking in a truk just by, Near Eighteen Hundred Pounds did lie. No sooner he had found the hoard, But he divulg’d it all abroad: Then shockt the neighbours, to behold, The Treasur’d bags of coyned gold. Thus did she cheat the battle such, They thought her poor; for she was rich: Her belly saved it for her CAT, But Puss must shew the will for that." Unfortunately, there's no word on what the cat did with her legacy, but hopefully she was able to get a nice mouse cobbler from time to time.

Not crazy though, right?

3 Comments

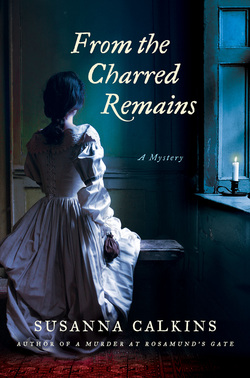

what bad event might have happened here? what bad event might have happened here? Since my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate, was published in 2013, I have gotten many questions about my writing process. “Are you a plotter or a pantser?” is the question I most often get. Back then, I didn’t even know what the question meant. Now I know the questioner wants to know whether I outline my books in elaborate detail before I start writing (plotting), or do I go by the seat of my pants (pantsing), figuring out the plot and details as I go. I want to say that I’m usually captivated by an opening image—and that’s what my story revolves around. For my first novel, I have a young woman walking innocently up to a man she knows, who then surprises her by sticking a knife in her gut. Who was this woman? Why did she trust this man? And of course, why did he kill her? (Ironically, the image that inspired A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate never even made it into the final version. I had written it as a prologue, but I worried about starting the story twice. You can check it out here, if you are interested.). However, I've now learned that some things truly need to be figured out before I start writing the book. As I start my fourth Lucy Campion novel, I thought I'd try to share something of my process of thinking through the plot. I have my opening image, and--for now--a one paragraph description of the plot: When the niece of one of Master Hargrave’s high-ranking friends is found on London Bridge, huddled near a pool of blood, traumatized and unable to speak, Lucy Campion, printer’s apprentice, is enlisted to serve temporarily as the young woman’s companion. As she recovers over the month of April 1667, the woman begins—with Lucy’s help—to reconstruct a terrible event that occurred on the bridge. When the woman is attacked while in her care, Lucy becomes unwillingly privy to a plot with far-reaching political implications. So I have my opening image, but now I have to start thinking through all the big questions. Initially, I seem to do this as a reader. Who is this woman? What happened to her? What was this terrible event? Was it something that she witnessed, or is she physically injured. Whose blood is it? Why is she on London Bridge alone?

Then I will start the hard part--thinking through these questions as a writer. I've definitely learned that I need to figure out who the antagonist is from the outset. My natural tendency is to reveal the story to myself (pantsing), probably because I'm naturally more interested in how terrible events affect a community, not why people do terrible things. However, that approach usually means I don't know whodunnit, and that's a challenge for a mystery writer! I usually have to do a lot of backtracking and rethinking motivations and actions, when I have not worked out who the killer is upfront. So then, my next set of questions will be plot-related. What is this terrible event that occurred? Why did it happen? Who caused it to happen? How did this young noblewoman get involved in such a thing? And--sadly enough--I need to figure out if the London Bridge will work as a backdrop. I know it got burnt in the Great Fire, but I'm not sure yet how feasible it is that she ends up there. Then, because Lucy needs to be brought in, I need to figure out what makes this so urgent. Will this woman be attacked under Lucy's care? Probably. Why? What does she know? What are the larger implications of this crime. So, over the next week or so, I will brainstorm these big questions, and from there--voila!--a plot of sorts will emerge for me. I will figure out anchor points, motivations, and subplots from there. Then I will start writing. Every time I hit a roadblock, I will just start the questioning process again, until I figure out the direction I need to take to move forward. So I will call my approach, Plot-Pantsing. What about you? If you are a writer, what approach do you prefer? As a reader, do you think you can tell which approach a writer took?  Anyone who knows me, knows I really love doing puzzles. Even when I was a kid, I was always doing puzzles--from word searches to crossword puzzles to substitution ciphers (probably because I felt like I was really decoding mysteries). But when I was in graduate school, I first encountered the fun of acrostics. In the high Middle Ages, scholars like Alcuin of York (Charlemagne's tutor) used to write short poems that contained clever messages--sometimes hidden--when read a certain way. In their simplest form, the first letter of each line would be carefully selected so that, when read down, the reader could discern a message. However, they could be more complex as well, which always fascinated me. I just knew that I had to work acrostics and other puzzles into my story, when I came across this acrostic published just after the Great Fire of London in 1666: London's Fatal Fal, an acrostic. Lo! Now confused Heaps only stand On what did bear the Glory of the Land. No stately places, no Edefices, Do now appear: No, here’s now none of these, Oh Cruel Fates! Can ye be so unkind? Not to leave, scarce a Mansion behind… Working out my own acrostic--and actually several hidden anagrams within the acrostic (shhh!!!)--was probably the most challenging and fun part of writing From the Charred Remains. But puzzles abound throughout the entire novel. There is even a secret hidden on the cover of the book, which you will understand after you read it!

Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 As I'm finishing up my third historical mystery--The Masque of a Murderer--I found that I still had a few more things to research. In particular, what would commoners living in 17th-century London have known of chocolate, and how might they have experienced it for the first time? References to "chocolate" in England can first be found in the 1640s. Of course, "chocolate" as a substance had been around for several thousand years as Smithonian.com explains, originating in Mesoamerica. However, it did not find its way to Europe until the early seventeenth century, as one of the strange products imported from the New World. The word "chocolate" comes from the Aztec word "xocoatl," (or is it the Nahuatl word chocolatl?) referring to a bitter drink derived from cacao beans, with medical and health properties (for more about the etymology of the word, check out Oxford Dictionaries blog for ten facts concerning the word Chocolate... ). By the 1650s, several discourses on the "physicks" and health properties of chocolate were in circulation in London. In 1640, "A Curious Treatise of the nature and quality of Chocolate" by Antonio Colmenero, a Spanish"Doctor in Physicke and Chirurgery, was translated into English. More significantly, Henry Stubb published the far more substantial treatise on "The Indian Nectar" in 1662. We know too, from a collection of 1667 statutes from King Charles II that there were restrictions on who could sell chocolate: "And be it further Enacted by Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said first day of September, no person or persons shall be permitted to sell or retail any Coffée, Chocolate, Sherbet or Tea, without License first obtained and had by Order of the General Sessions of the Peace in the several and respective Counties,etc etc." This makes me reasonably certain that chocolate would have been sold at coffee houses, for those would have been the establishments likely to acquire such a license. It is unlikely that chocolate would have been sold at taverns or alehouses, at least in early Restoration England, due to the great dispute between those who sold wine and beer, and those who sold coffee. Chocolate might have been procured for medicinal purposes as well, although it is unclear to me--at least at this preliminary stage--whether it would have been actively prescribed by a physician. However, if the "Virtues" are to be believed (of course, that's if they are to believed), chocolate cures infertility, "ill complexion," digestive illnesses, consumption and "coughs to the lungs," "sweetens the breath," "cleaneth the teeth," "provoketh urine" and "cureth the stone." Apparently, this miracle drug also cures "the running of the reins," (the last a euphemistic biblical reference to venereal disease). Who knew? I have to surmise a bit here, on how popular chocolate truly was in Restoration London. But I think it's reasonable to assume, especially once sugar became a more common household good, that it would have been become popular fairly quickly. (Although it's also likely that it remained in the realm of the elite and wealthy, for quite some time.) But what do you think? England and Wales. A collection of the statutes made in the reigns of King Charles the I. and King Charles the II. with the abridgment of such as stand repealed or expired. Continued after the method of Mr. Pulton. With notes of references, one to the other, as they now stand altered, enlarged or explained. To which also are added, the titles of all the statutes and private acts of Parliament passed by their said Majesties, untill this present year, MDCLXVII. With a table directing to the principal matters of the said statutes. By Tho: Manby of Lincolns-Inn, Esq. 1667 Wing (CD-ROM, 1996) / E898

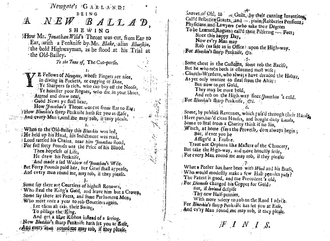

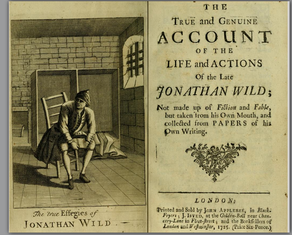

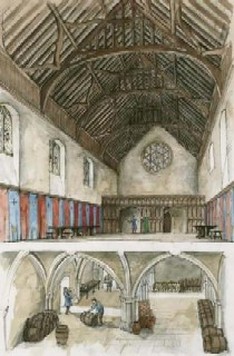

Wing / 2532:08  Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  Today, I'm taking part in a "blog hop" celebrating the launch of Castles, Customs and Kings, a compilation of essays from the English Historical Fiction Authors blog. If you go to the blog, you can enter for a chance to win a free copy! "Read the history behind the fiction and discover the true tales surrounding England's castles, customs, and kings." --Official excerpt  I have a piece in here about the political activities of Quaker women, who spent a lot of time speaking against the King. But today, since a number of bloggers are discussing palaces and castles, I thought I would write about my personal experience living near the ruins of Winchester Palace in London. ***********************************************************************************  Photo: Mike Peel. 2009. www.mikepeel.net Photo: Mike Peel. 2009. www.mikepeel.net When I was a pirate serving aboard the Golden Hinde, the museum replica of Sir Francis Drake's ship dry-docked in the Thames--(okay, I was a tour guide or 'living history interpreter')--I spent a lot of time gazing at the ruins of Winchester Palace. Located in Southwark, near Shakespeare's Globe, the Clink and the Anchor (most fun pub in London), the ruins of the 13th century Winchester Palace loom incongruously from a modern parking garage (Car park!)  Liam Wales © Eng. Her. Photo Library Liam Wales © Eng. Her. Photo Library Not to be confused with the more illustrious Winchester Castle--or Winchester Cathedral, as many a dismayed tourist has done—Winchester Palace was founded by Bishop Henry de Blois, brother of King Stephen, in the early 13th century. It was designed to serve as a place for visiting bishops to stay when they journeyed to London. According to the English Heritage website, the Palace once consisted of a Great Hall, which led to a buttery, pantry and kitchen. In its late medieval heyday, the Palace had been a site of great spectacle, feasts and grand dinners, even have hosted the wedding dinner of James I of Scotland and Joan Beauford in 1424. The majestic qualities of the palace are suggested by the presence of a rose window, a common feature of more lavish churches and palaces built in this time. There is also evidence that the palace had a tennis court, bowling alley and pleasure gardens, to keep the bishops entertained while on royal and administrative business. Underneath the hall was a vaulted wine cellar, no doubt full of great vats and bottles to keep the bishops and their guests merry. There was also a passageway to the river wharf along the south bank of the Thames, to bring supplies into the Palace. The palace seems to have been surrounded around two courtyards, a brew-house and butchery. The Clink prison, under the auspices of the Bishop of Winchester, was also nearby. (Yes, this is where we get the phrase being ‘thrown in the clink.’)  The Rose Window http://www.english-heritage.org.uk The Rose Window http://www.english-heritage.org.uk After the Reformation and King Henry VIII’s dissolution of many church properties, the palace changed its purpose. By the 17th century it was divided into tenements and warehouses. In the 19th century, much of the palace was destroyed in a fire in 1814. The ruins remained in disrepair until the 1980s when the area began to be redeveloped. Now only the bare remains and beautiful rose window suggest the former grandeur of the Palace. When I used to lead school children on tours of the ship, we’d often pause by the Palace ruins. There, I couldn’t help but whisper about the mysterious happenings the Golden Hinde crew had all witnessed during our long moonlit stints on ship watch... A shadow moving slowly through the grounds, when the source of the movement could not be detected.... A flock of black birds, arrayed in a perfect circle, as if convened at a great table.... And most odd of all: one night, our whole crew heard the strands of a madrigal being sung from deep within the ruins...By the time one of us mustered up the courage to peer over the guardrail, the unknown singers had vanished. To this day, I sometimes wonder who those anonymous singers were... But that's the intriguing romance and mystery of the ruins of Winchester Palace....  I was so ready to go on vacation, traveling to Philly and South Dakota, that of course I forgot to put up an official 'blog hiatus!' So thanks to those who checked back to see if I wrote anything new. So while I'm still in procrastination, er, vacation mindset, I got to thinking about that time-old question: Why do we Yanks 'take a vacation', while our chums across the pond 'go on holiday?' It turns out that, once again, we can blame our Puritan forefathers for the distinction. The original meaning Originally, the word "vacation" comes from old English, and until the early nineteenth century, it meant something different from our modern U.S understanding of the term. According to our trusty Oxford English Dictionary, the word "vacation" referred to the release or respite from some business, occupation or other activity. For example, in the prologue to the "Wife of Bath," Chaucer (c. 1386) wrote: "Whan he hadde leyser and vacacioun From oother worldly occupacioun." ("When he had leisure and vacation from other wordly occupation.") Vacation could also refer to leisure time for a specific purpose, such as when Thomas a Kempis (c.1450) instructed his readers to "Put the vacacion of god before all other things." Keep this definition in mind. Vacation also referred to those periods when law-courts, universities, or school were formally suspended or closed. In 1456, R. Pecock complained: "Hou myche labour is maad in ynnes of Court in Londoun, bi tymes of vacacioun, aboute the reding..of the Kingis Statutis." (How much labor is made in Inns of Court in London, [during] times of vacation, about the reading...of the King's Statutes.") I believe that this understanding is still common in the United Kingdom today, but feel free to let me know if I'm incorrect. These conceptions of the word "vacation" seem to have transported to the American colonies, and were in use until about the mid-nineteenth century. At this time, a shift in the understanding of the word "vacation" occurred. The shift in understanding According to Cindy Aron, professor of history emeriti at the University of Virginia, the modern U.S. notion of "vacation" first emerged among the elites in the early nineteenth century. While European aristocrats and the middling sorts had long taken excursions for pleasure, (at least back to the Middle Ages, if not the Roman times), such frivolity and hedonism was looked at a bit more askance here in the U.S. Long-held Puritan and Protestant beliefs about idleness and morality certainly kept the middle and working classes in check. In the early 19th century, however, physicians began to cajole their wealthy patients to take a "vacation," for their spiritual and physical health (re-framing those older definitions described above). They did not use the term 'holiday' which probably conjured images of merrymaking and hedonism, and was, in effect, a harder sell. Gradually, the idea of taking a vacation for one's health began to find a hold among the middle class as well. Certainly, the emergence of the railroads dramatically changed the way people thought about travel, particularly for leisure purposes. Previously inaccessible places (including such restorative places as lakes, oceans, hot springs etc) could now be readily reached by train, often for far less money than for a hired hack. Even more interestingly, Aron explains, is that Churches, particularly the Methodists, began to create religious campgrounds and resorts in the mid-nineteenth century. These were designed to appealed to those with holding an ethic that revolved around hard work, discipline and morality (e.g. the middle class). Such places offered a means to "get away from it all" while at the same time, allowing vacationers to feel they had not taken leave of their morals and virtues. "Organized idleness!" By the early twentieth century, members of the working class began to "take vacation" as well. Vacation was no longer a leisure pursuit of the privileged elite, but was rapidly becoming an expectation for most families. Motels, hotels, spas, and resorts became an industry in themselves, many emphasizing affordability and accessibility to attractions. Throughout the twentieth century, many establishments deliberately focused on supplying fun, hedonism and all the vices (Las Vegas, anyone?), and were far less concerned with offering an environment to rejuvenate the body and soul. So "taking a vacation" has certainly transformed over time. Personally, I find it really interesting that leisure had to be legitimated by Americans. Oh, how those Puritan impulses still linger! But whether you're on holiday, or taking a vacation, I hope you are enjoying your organized (unorganized?) idleness. I'll be blogging again soon. Right now, I'm on vacation from my vacation! Reference: Aron, C (1999).Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States.

Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 I had to laugh when I came across this tract by John Raymond, 17th century author of Folly in Print, or A Book of Rymes (1667). Right away, on the first page, he lets the readers know it really isn't his fault if you don't like his book: "Whoever buyes this Book will say, Next, Raymond then explains to his readers that if they believe what the bookseller says (or sings, as was often the case), it's their own fault if they find they don't like the book after all. "... in Books, where for money or exchange, we take our choice, and in our own Election please our selves; Can you imagine if authors could still add this type of caveat emptor today? Madness! But I'm sure there are many authors today--especially those stung by hurtful reviews--who might wish they could say something like this to their readers: I doe not promise for my Book nor say 'tis good, but here's variety and each man (of his own pallat) is the certain judge: You might like my book, you might not. To each her own!

But what do you think? Have you ever felt deceived about a book?  In seventeenth-century England, the role of servants was far more nuanced and flexible than readers today may realize. Certainly, there was a long-standing patriarchal expectation that the head of a family would maintain a godly and dutiful order over his household. In advice manuals, published letters and sermons, men were repeatedly admonished on how to treat the servants living in their homes. Men were expected to provide food, shelter, religious instruction, and a disciplined hand, much as they were expected to treat their own children and wives. They were not supposed to treat their servants as slaves; indeed, quite the opposite. However, we must always consider the tensions between prescription and practice. Just because the expectations were stated, most certainly does not mean that the expectations were met. For example, in Advice of a father, or, Counsel to a child (1664), men were admonished to:

For this reason, as the last injunction suggests, discretion was particularly important (perhaps because it was not always be realized). The Early English Books are full of tales of servants blackmailing their employers, because they had discovered something the master (or mistress!) would rather have kept hidden (e.g. adultery, gambling debts, infanticide etc). Thus, the same advice manual warns:

This last point suggests that even the lowest servant in his employ should be treated as all the other servants were treated.While the master was expected to rule with a firm hand, he was more like a benevolent monarch than a tyrant:

There's a pragmatic realization here that seems to transcend the ages. If you work someone without letting them "blow off steam," then you run the risk of having unmotivated, even hostile or violent, servants in your household. This holds with the reality of homicide trends in the 17th century: Far more servants killed their masters, than masters killed their servants! This injunction also fits in with the many accounts across the Early English books of servants getting some days off, attending the theatres and fairs, going to market, visiting family, even sharing in merriments with the family. While the author of this piece would mostly likely call for moderation, it's clear that masters did give their servants more freedoms than might be assumed.  Anon. (1664). Advice of a father Anon. (1664). Advice of a father I want to point out one other piece of advice offered in this manual: "Reckon thy servants among thy children; the difference is only in degrees; both make up the economy; thou art the father of the family; a wife servant is better than a foolish child; cast him not off in an old age, when he has spent himself in thy service; a faithful servant does well deserve to be counted among thy friends." There was, without a doubt, a recognition that loyal servants could become more like members of the family over time. In this particular injunction, the master is told not to throw out his servants just because they have become old, but rather to take care of them. The best example I can think of, to help illustrate how a servant could become like a family member over time, is to draw on a 1960s reference: Would the Brady Bunch have thrown out Alice? In my recent novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, I touch on a lot of these issues. I deliberately placed my protagonist Lucy Campion, in the household of a magistrate, at a time when Enlightened principles were starting to emerge in England. In my story, I deliberately juxtapose the reasoned household of the magistrate, with the less disciplined households that surrounded them. I wanted my magistrate then to be a more Enlightened thinker, more concerned with ideas, than the person who suggested those ideas to him. So he could have listened to and believed in the views of a servant with an intelligent lively mind. Perhaps I gave Lucy too many freedoms, perhaps I didn't. Ultimately, I do not think there is any blanket, all-encompassing way to look at the relationship between masters and servants in 17th century England. Arguably, these attitudes may have changed in the 18th and 19th century (although I doubt there was a monolithic understanding of this relationship even then), but the bottom line is this: The relationship between master and servant in the 17th century was far more nuanced and flexible than is often assumed. This is my story, and I'm sticking to it! Because I think in metaphors, this Syrian water wheel perfectly explains my absence from my blog. Since A Murder at Rosamund's Gate released a month ago (has it been that long already?!), I've barely done any writing. I've been so busy with my day job (faculty development), my night job (teaching), my all-the-time job (family), not too mention all the fun book-related events I've been doing, that I've been neglecting my super-late-at-night job (writing).

And I miss writing. For me, writing is just fun. The problem-solving, the research, the dreamy imaginings, the discovery of character and motives, the joy of putting down the perfect word at the perfect moment...It's all a process I truly enjoy. Yet, I'm conscious of being like the Syrian water wheel above. Immobile. Fixed. Dessicated. (Temporarily, I hope!). Normally, as each of my little cups bearing water gets emptied, it will soon swish down through the water to be replenished. Right now, I think I've emptied one too many cups. As the noted psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi might say, my flow of creativity has been halted. (Check out his Ted Talk on the secret of happiness and connecting with your creative self.) But I'm excited. In a few weeks, the academic year will have ended, I'll have turned in grades, wrapped up the programs I run, completed some work travel, and then I'll have time to write--and perhaps more importantly--the flow will return, and I'll get that water wheel turning again. But I'm curious...do you have a metaphor or mental image for how you think about writing, (or anything else that you particularly enjoy?) |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed