I was so ready to go on vacation, traveling to Philly and South Dakota, that of course I forgot to put up an official 'blog hiatus!' So thanks to those who checked back to see if I wrote anything new. So while I'm still in procrastination, er, vacation mindset, I got to thinking about that time-old question: Why do we Yanks 'take a vacation', while our chums across the pond 'go on holiday?' It turns out that, once again, we can blame our Puritan forefathers for the distinction. The original meaning Originally, the word "vacation" comes from old English, and until the early nineteenth century, it meant something different from our modern U.S understanding of the term. According to our trusty Oxford English Dictionary, the word "vacation" referred to the release or respite from some business, occupation or other activity. For example, in the prologue to the "Wife of Bath," Chaucer (c. 1386) wrote: "Whan he hadde leyser and vacacioun From oother worldly occupacioun." ("When he had leisure and vacation from other wordly occupation.") Vacation could also refer to leisure time for a specific purpose, such as when Thomas a Kempis (c.1450) instructed his readers to "Put the vacacion of god before all other things." Keep this definition in mind. Vacation also referred to those periods when law-courts, universities, or school were formally suspended or closed. In 1456, R. Pecock complained: "Hou myche labour is maad in ynnes of Court in Londoun, bi tymes of vacacioun, aboute the reding..of the Kingis Statutis." (How much labor is made in Inns of Court in London, [during] times of vacation, about the reading...of the King's Statutes.") I believe that this understanding is still common in the United Kingdom today, but feel free to let me know if I'm incorrect. These conceptions of the word "vacation" seem to have transported to the American colonies, and were in use until about the mid-nineteenth century. At this time, a shift in the understanding of the word "vacation" occurred. The shift in understanding According to Cindy Aron, professor of history emeriti at the University of Virginia, the modern U.S. notion of "vacation" first emerged among the elites in the early nineteenth century. While European aristocrats and the middling sorts had long taken excursions for pleasure, (at least back to the Middle Ages, if not the Roman times), such frivolity and hedonism was looked at a bit more askance here in the U.S. Long-held Puritan and Protestant beliefs about idleness and morality certainly kept the middle and working classes in check. In the early 19th century, however, physicians began to cajole their wealthy patients to take a "vacation," for their spiritual and physical health (re-framing those older definitions described above). They did not use the term 'holiday' which probably conjured images of merrymaking and hedonism, and was, in effect, a harder sell. Gradually, the idea of taking a vacation for one's health began to find a hold among the middle class as well. Certainly, the emergence of the railroads dramatically changed the way people thought about travel, particularly for leisure purposes. Previously inaccessible places (including such restorative places as lakes, oceans, hot springs etc) could now be readily reached by train, often for far less money than for a hired hack. Even more interestingly, Aron explains, is that Churches, particularly the Methodists, began to create religious campgrounds and resorts in the mid-nineteenth century. These were designed to appealed to those with holding an ethic that revolved around hard work, discipline and morality (e.g. the middle class). Such places offered a means to "get away from it all" while at the same time, allowing vacationers to feel they had not taken leave of their morals and virtues. "Organized idleness!" By the early twentieth century, members of the working class began to "take vacation" as well. Vacation was no longer a leisure pursuit of the privileged elite, but was rapidly becoming an expectation for most families. Motels, hotels, spas, and resorts became an industry in themselves, many emphasizing affordability and accessibility to attractions. Throughout the twentieth century, many establishments deliberately focused on supplying fun, hedonism and all the vices (Las Vegas, anyone?), and were far less concerned with offering an environment to rejuvenate the body and soul. So "taking a vacation" has certainly transformed over time. Personally, I find it really interesting that leisure had to be legitimated by Americans. Oh, how those Puritan impulses still linger! But whether you're on holiday, or taking a vacation, I hope you are enjoying your organized (unorganized?) idleness. I'll be blogging again soon. Right now, I'm on vacation from my vacation! Reference: Aron, C (1999).Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States.

5 Comments

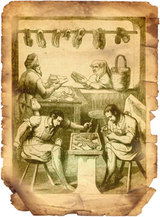

Quick! What do these celebrities--Will Smith, Elizabeth Taylor, Tina Turner, Monica Potter, and Bradley Cooper--all have in common? Hint: It's something medieval.... Each bears the last name of a medieval/early modern occupation. (Smith and taylor/tailor are self-explanatory, but a turner operated a lathe, a cooper made barrels, and a potter, well, potted). I was thinking about this--how many early modern guilds are still represented in surnames today--as I was doing research for my second novel, From the Charred Remains (2013). I had come across the occupation of “cordwainer.” Cordwainer? I knew this was an occupation, like a tinker, or a wainwright (wheelmaker) or a hooper (another name for barrel-maker), but I have to admit, I never thought to look this one up.  The cordwainer crest Any guesses?..... No? Well, it turns out a “cordwainer” is a shoemaker. The term originated in medieval Cordoba in Spain, a region controlled by Muslims who excelled, among other things, in the production of high-quality specially-tanned leather. (See the goats in the guild crest?)  cordwainers at work The French referred to those who made shoes from this leather as cordonnier, which became “cordwainer” in England (you know, after that little Norman invasion of England in 1066). According to the website for the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers--yes, the medieval guild still exists today as a charitable group!—the cordwainer must be distinguished from the cobbler. The cordwainer only worked with new leather, while the cobbler could only work with old. (Indeed, cobblers could get in a lot of trouble if they were found with new leather).  mmm...leatherless cobbler pie And the more important question of all? What does any of this have to do with blueberry cobbler? (Only that early American settlers used to make pie from any foodstuffs on hand-- cobbling it together as a cobbler would piece together shoes...Maybe Will Smith likes blueberry cobbler too, I don't know.) What do you think? Do you know of any surnames--celebrity or otherwise--that have an interesting history?  Chaucer--the man knew birds I'll leave it to other writers to focus on the fascinating, but much contested, history of Valentine's Day. They can sort out how the medieval Church may have appropriated the ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia (already being held in mid February); decide whether Valentine, a third century Bishop, had indeed been beheaded for holding secret marriages; and debate whether as a saint, he truly restored a blind woman's sight. (And for goodness sake, will we ever agree whether Valentine really signed his final letter with these immortal words: 'From your Valentine?') These questions are important--after all, an entire industry depends on these re-purposed, glossed-over events to thrive. But, for me, the history of Valentine's Day would be nothing without the birds and, of course, the buns.  some really smart birds First, the birds. I've seen repeated many times this story that medieval people believed that birds mated on February 14. It doesn't help that Chaucer seemed to confirm this belief in his fourteenth century Parliament of Fowls, "For this was on St. Valentine's Day, When every fowl cometh there to choose his mate." (Birds, apparently, were smarter than people. Despite all the calendar changes--from Julian to Gregorian--that confused ordinary people, birds could figure out when February 14 was).  caraway buns--the makers of romance? So, of course, with birds, must come buns... Logically, then, if you believed that birds mated on Valentine's Day, then it's only rational to eat as birds do. Thus, many people ate buns with caraway seeds on February 14 too, hoping to entice a mate. (Am I the only one imagining people sitting around with their pints of ale, taking turns pecking at buns on their own and other people's plates...?) So this year, why not forgo the chocolates, and bring on the seeds?! And here is a traditional caraway seed bun recipe, in case, like me, you've never made such a thing in your life. So long as you don't say "Romance is for the birds!" (Sorry, couldn't resist!) I'm curious, though, does anyone still eat these buns on Valentine's Day? And other than chocolate and candy, does anyone have any traditional Valentine's day food? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed