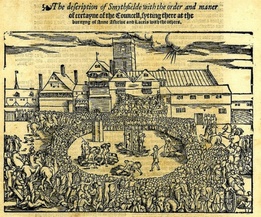

Civitas Londinum, 1561 Civitas Londinum, 1561 Like the lost River Fleet, another location in London that has long intrigued me is the infamous Smithfield market; a site of enormous contrasts: executions and extreme devotions, torture and merry-making. In the Middle Ages, Smithfield--"a smooth field" to the north of London's walls--was a natural place for jousts, tournaments, and the selling and butchering of livestock. Conveniently (!), animal waste from the market could be dumped into the River Fleet, which flowed into the Thames. It’s original origins as a place where livestock could be bought and sold, can be seen in the vestiges of its street names (e.g. Cow lane, Cock lane).  Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Not surprisingly, Smithfield, like most great open communal spaces was used for greatly varied purposes, including: Public torture: Over the centuries, many criminals—particularly those accused of treason—were tortured. One of the most famous was William Wallace (“Braveheart”)- - a twelfth century hero of the Scottish people. Drawing and quartered was the preferred method, and perhaps castrated as well (but studio executives probably thought movie audiences couldn’t stomach Mel Gibson undergoing that particular humiliation.)  Public executions: While Smithfield was a regular site of hangings and burnings for centuries, under Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary” to her detractors), quite a few Protestant dissenters were publicly burned as heretics. [Interesting side note: According to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, the “Marian Martyrs” would ask that their hands not be bound and their wood pile would consist of the greenest wood, so that their plaintive laments and prayers would last longer.) The burnings of these men and women were collectively referred to as “The Smithfield Fires.” Merry-making and Fair-going: Every August until the mid-seventeenth century, St. Bartholomew’s fair would be held at Smithfield. Originally it was supposed to be only three days of merry-making, but by the 17th century the fair was lasting over two weeks. Check out this advertisement for the entertainment to be had at the “Plow Music Booth” in 16xx:  Anon (1679) Anon (1679) “At the Plow-Music Booth in Smith Field Rounds, (a Red flag being on the Top) during the Time of Bartholomew-Fair, you may be entertained with excellent sports, [such as] Antique dances, entries, cerebrands and jigs, a little girl about 6 years old who danceth with two naked rapiers at her throat, to the admiration of all that ever see her…. With good Wine, Cider, Mum and Mead, and good music for the accommodation of those who are inclined to mirth.”  Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Or of course, for "all single men and bachelors," there was also an ongoing "auction of whores," which--as Michael Altham (1691) joked--contained, “a curious collection of painted whores, cracks, night-walkers, newgate-nappers, bridewell-workers, ladies of pleasue, cart-dancers; with other such dissembling pick-pocket cheats, some pox’d, some clap’d, and some quite rotten and ready to fall in pieces.” Underlying this bill, however a real fear of disease and pollution that seemed to occur whenever so many people were brought in such close proximity. King Charles I tried to cease the Fair on several occasions during his reign. In 1637, he issued a proclamation for putting off the Bartholomew Fair, and a similar fair in Southwark:  Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 “Whereas his Majesty hath taken special care and given several directions, that the usual assemblies and concourse of people might be omitted and forborne, the better to prevent the danger and increase of the infection: Yet finding that the plague is dispersed in sundry places in and near the City of London, his majesty in pursuance of those direction and out of his continual care of the safety of his subjects in general, and of the said city in particular, and to cut off all occasions that may conduce to the further spreading of the sickness, doth hereby declare his royal will and pleasure for the putting off this next fair…” This was only a temporary halt to such festivities; only Cromwell was able to completely stop the fun. The Fair, like all other such festivals, was banned under his regime, only to be restored in 1666 with the Restoration of the fun-loving Charles II.  Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Today, there is little indication of the mass executions and torture that occurred here, although Smithfield Market—now called the Central London Market—is the largest of its kind in London, and one of the largest in all of the European Union. But like the River Fleet, the Smithfield grounds are another part of secret London.

1 Comment

In my third historical mystery, The Masque of a Murderer, Lucy Campion, printer's apprentice, has been asked to record the last words of a dying Quaker. He had been run over by a cart and horse the day before, and was slowly dying from his extensive injuries. A number of people have gathered by his bedside, listening to his final rambling words, testifying to his journey from sinner to one who has found the "Inner Light." And before the man finally succumbs, he regains a moment of lucidity and manages to tell Lucy that he had, in fact, been pushed in front of the horse and his death was no accident. Moreover, he believed that his murderer had to be one of his closer acquaintances, perhaps even a fellow Quaker. The premise came from a tradition that was common in early modern England of recording the "last dying speeches" of different types of individuals. Such speeches were common for criminals about to be executed, for example, and which would be distributed at the gallows for eager spectators. [In From the Charred Remains, I have Lucy selling some of these at the public hanging of a criminal]. Often written by clergymen, such chapbooks or pamphlets were usually both pious and didadic in tone. As historian J.A. Sharpe has put forth: “The gallows literature illustrates the way in which the civil and religious authorities designed the execution spectacle to articulate a particular set of values, inculcate a certain behavioral model and bolster a social order perceived as threatened. Only a small number of people might witness an execution, but the pamphlet account was designed to reach a wider audience.”*  Wing W2039 Wing W2039 Indeed, there was a similar quality to other types of sinner's journeys that were published as chapbooks or pamphlets. Quakers, who produced hundreds of tracts in the 17th century, frequently recorded the last words of Friends whom they wished to hold up as a means to extol a certain value or set of virtues for others. For example, when I was writing my dissertation on 17th century Quaker women, I came across a poignant tract--The Work of God in a Dying Maid (1677)**--written by one of the more prominent Quaker leaders, Joan Whitrowe, detailing the death of her daughter, fifteen-year old Susannah. The 48-page tract tells the story, not just of Susannah's death, but of the young girl's early struggles with temptation. The testimonies, written by Joan and other local leaders, demonstrates how Quaker children and youth were supposed to behave, and why they should listen to the advice of their parents and other elders. Indeed, Joan dedicates the work as a warning to those wayward souls, "who are in the same condition [Susannah] was in before her sickness." But the back story that emerges throughout the pious testimonies is quite compelling. As Susannah lay dying in her Middlesex home in 1677, neighbors whispered that the cause of her "distemper" was a recently thwarted romance. Questioned by her parents, the young Quaker admitted that a certain man was "very urgent with [her] upon the account of Marriage" and since her father had been a "little harsh" to her she thought she would set herself "at liberty." But upon reconsideration she allegedly told her suitor, "I would do nothing without my Father and Mother's advice." She assured her mother, "before I fell sick this last time, I did desire never to see him more." [Here are some of the lessons about virtue and obeying one's parents--and the consequences of not doing so.] Feverish, restless, and in pain, the young Quaker reportedly clamored for God's swift judgment, mercy, and an end to her suffering. For six days her mother and father and various friends maintained an anxious vigil at her bedside, praying and recording Susannah's final excited visions and earnest penitent speeches to God. She chastised herself for her vanity, "How often have I adorned myself as fine in their [her female acquaintances] fashions as I could make me?" She berated herself for bringing shame to her family and lamented speaking out against her mother’s sect: "Oh! How have I been against a woman's speaking in a [Quaker] meeting?" What we can not know of course, is how much of this Susannah actually said, and how much was expanded upon in the written narrative to make the larger point about godliness. But it gives a sense of the way that people's final words were recorded, and it offers a fascinating backdrop for a murder mystery... *J. A. Sharpe, "Last Dying Speeches": Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England. Past & Present No. 107 (May, 1985), pp. 144-167. quote on p.148.

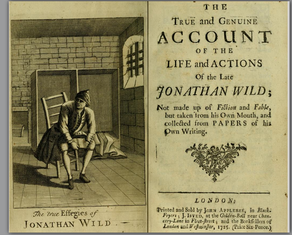

Joan Whitrowe, The Work of God in a Dying Maid: Being a Short Account of the Dealings of the Lord with one Susannah Whitrowe (n.p., 1677), 16.  Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed