I went on to write two other mysteries, Murder Knocks Twice and The Fate of a Flapper set in 1929 Chicago, featuring Gina Ricci, a cocktail waitress in a Chicago speakeasy. (And some readers have asked me if Gina is Lucy's great-great-great-great-great granddaughter, and I always say, 'sure why not?' When the series is complete maybe I'll work out Gina's genealogy). I honestly thought that my time with Lucy and 17th century London would be over after DARF was published. But then Severn House approached me about writing another Lucy, and continuing the series, and I jumped at this amazing opportunity.

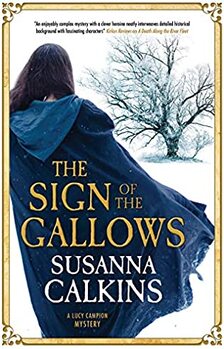

Getting back into Lucy's world was not nearly as difficult as I imagined. Essentially I just had to push my cocktail glasses off the table, stack my Prohibition books back on the shelf, and change my music from flappers fun to classical (I can't quite bring myself to listen to madrigals and baroque music, or drink mead for that matter, to get myself in the right mood). Each of my first four Lucy books all came to me in the form of an image, and The Sign of the Gallows was no exception. I immediately had the image of Lucy standing at a crossroads, because that's where I mentally pictured her (and me) to be. It can't get more "on the head" than that. This image was particularly appealing location for a mystery because in the 17th century a crossroads was still very much viewed as a dangerous and frightening place. Murderers and suicides were often buried at crossroads since they could not be buried in sacred grounds. The idea was that their tortured spirits would not be able to find their way back home and they'd get confused at a crossroads. That also meant, of course, that travelers needed to be wary, when passing through a crossroads, lest they attract one of these unfortunate souls and carry them back home with them.... That image gave way to a plot...Lucy discovers a dead man hanging from a gallows at the crossroads, drawing her into a puzzling mystery. The image of Lucy at the crossroads also informed Lucy's lot in life, and I wrote much of the novel with the idea that Lucy would be on a definite path by the story's close. However, ironically, just as I was writing the last chapter, I was asked by Severn House to write a sixth Lucy Campion mystery-- which meant I had to rethink Lucy's crossroads conundrum. A fun challenge to have! It's been so fun to jump back into Lucy's world. As I was writing, I did have this weird sense my characters had been waiting for me. A little like Pirandello's "Six Characters in Search of an Author," only the 17th century version. (Although that's a little disturbing, if you think about it too much). It's been really gratifying to be able to move Lucy's story forward, and to tell a story I never thought would be told.

8 Comments

I'm so happy and honored to say that my third historical novel, The Masque of a Murderer, officially launches today, April 14! And while I may not be quite as giddy when my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate (2013) launched two years ago--because nothing can ever compare to the release of a first novel--I'm still as loopy as I was last year, when From the Charred Remains (2014) entered the world. Recently, in preparation for the launch, I've been answering a lot of fun and interesting questions about The Masque of a Murderer (the historical background, the story and characters, and my writing process etc). So, I thought I'd do a quick round-up here! I welcome you to:

Thanks so much for sharing this journey with me!!! And I appreciate all the bloggers and reviewers who hosted me, including those through Amy Bruno's Historical Fiction Virtual Blog Tours! And I'm always so grateful to the wonderful people at Minotaur, especially Kelley Ragland and Elizabeth Lacks, and my agent David Hale Smith, and of course my wonderful alpha reader, Matt Kelley!! (and now, I turn my attention back to A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, due out April 2016!!!!)  what bad event might have happened here? what bad event might have happened here? Since my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate, was published in 2013, I have gotten many questions about my writing process. “Are you a plotter or a pantser?” is the question I most often get. Back then, I didn’t even know what the question meant. Now I know the questioner wants to know whether I outline my books in elaborate detail before I start writing (plotting), or do I go by the seat of my pants (pantsing), figuring out the plot and details as I go. I want to say that I’m usually captivated by an opening image—and that’s what my story revolves around. For my first novel, I have a young woman walking innocently up to a man she knows, who then surprises her by sticking a knife in her gut. Who was this woman? Why did she trust this man? And of course, why did he kill her? (Ironically, the image that inspired A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate never even made it into the final version. I had written it as a prologue, but I worried about starting the story twice. You can check it out here, if you are interested.). However, I've now learned that some things truly need to be figured out before I start writing the book. As I start my fourth Lucy Campion novel, I thought I'd try to share something of my process of thinking through the plot. I have my opening image, and--for now--a one paragraph description of the plot: When the niece of one of Master Hargrave’s high-ranking friends is found on London Bridge, huddled near a pool of blood, traumatized and unable to speak, Lucy Campion, printer’s apprentice, is enlisted to serve temporarily as the young woman’s companion. As she recovers over the month of April 1667, the woman begins—with Lucy’s help—to reconstruct a terrible event that occurred on the bridge. When the woman is attacked while in her care, Lucy becomes unwillingly privy to a plot with far-reaching political implications. So I have my opening image, but now I have to start thinking through all the big questions. Initially, I seem to do this as a reader. Who is this woman? What happened to her? What was this terrible event? Was it something that she witnessed, or is she physically injured. Whose blood is it? Why is she on London Bridge alone?

Then I will start the hard part--thinking through these questions as a writer. I've definitely learned that I need to figure out who the antagonist is from the outset. My natural tendency is to reveal the story to myself (pantsing), probably because I'm naturally more interested in how terrible events affect a community, not why people do terrible things. However, that approach usually means I don't know whodunnit, and that's a challenge for a mystery writer! I usually have to do a lot of backtracking and rethinking motivations and actions, when I have not worked out who the killer is upfront. So then, my next set of questions will be plot-related. What is this terrible event that occurred? Why did it happen? Who caused it to happen? How did this young noblewoman get involved in such a thing? And--sadly enough--I need to figure out if the London Bridge will work as a backdrop. I know it got burnt in the Great Fire, but I'm not sure yet how feasible it is that she ends up there. Then, because Lucy needs to be brought in, I need to figure out what makes this so urgent. Will this woman be attacked under Lucy's care? Probably. Why? What does she know? What are the larger implications of this crime. So, over the next week or so, I will brainstorm these big questions, and from there--voila!--a plot of sorts will emerge for me. I will figure out anchor points, motivations, and subplots from there. Then I will start writing. Every time I hit a roadblock, I will just start the questioning process again, until I figure out the direction I need to take to move forward. So I will call my approach, Plot-Pantsing. What about you? If you are a writer, what approach do you prefer? As a reader, do you think you can tell which approach a writer took?  Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 Anon. 1660 Wing / 1961:07 As I'm finishing up my third historical mystery--The Masque of a Murderer--I found that I still had a few more things to research. In particular, what would commoners living in 17th-century London have known of chocolate, and how might they have experienced it for the first time? References to "chocolate" in England can first be found in the 1640s. Of course, "chocolate" as a substance had been around for several thousand years as Smithonian.com explains, originating in Mesoamerica. However, it did not find its way to Europe until the early seventeenth century, as one of the strange products imported from the New World. The word "chocolate" comes from the Aztec word "xocoatl," (or is it the Nahuatl word chocolatl?) referring to a bitter drink derived from cacao beans, with medical and health properties (for more about the etymology of the word, check out Oxford Dictionaries blog for ten facts concerning the word Chocolate... ). By the 1650s, several discourses on the "physicks" and health properties of chocolate were in circulation in London. In 1640, "A Curious Treatise of the nature and quality of Chocolate" by Antonio Colmenero, a Spanish"Doctor in Physicke and Chirurgery, was translated into English. More significantly, Henry Stubb published the far more substantial treatise on "The Indian Nectar" in 1662. We know too, from a collection of 1667 statutes from King Charles II that there were restrictions on who could sell chocolate: "And be it further Enacted by Authority aforesaid, That from and after the said first day of September, no person or persons shall be permitted to sell or retail any Coffée, Chocolate, Sherbet or Tea, without License first obtained and had by Order of the General Sessions of the Peace in the several and respective Counties,etc etc." This makes me reasonably certain that chocolate would have been sold at coffee houses, for those would have been the establishments likely to acquire such a license. It is unlikely that chocolate would have been sold at taverns or alehouses, at least in early Restoration England, due to the great dispute between those who sold wine and beer, and those who sold coffee. Chocolate might have been procured for medicinal purposes as well, although it is unclear to me--at least at this preliminary stage--whether it would have been actively prescribed by a physician. However, if the "Virtues" are to be believed (of course, that's if they are to believed), chocolate cures infertility, "ill complexion," digestive illnesses, consumption and "coughs to the lungs," "sweetens the breath," "cleaneth the teeth," "provoketh urine" and "cureth the stone." Apparently, this miracle drug also cures "the running of the reins," (the last a euphemistic biblical reference to venereal disease). Who knew? I have to surmise a bit here, on how popular chocolate truly was in Restoration London. But I think it's reasonable to assume, especially once sugar became a more common household good, that it would have been become popular fairly quickly. (Although it's also likely that it remained in the realm of the elite and wealthy, for quite some time.) But what do you think? England and Wales. A collection of the statutes made in the reigns of King Charles the I. and King Charles the II. with the abridgment of such as stand repealed or expired. Continued after the method of Mr. Pulton. With notes of references, one to the other, as they now stand altered, enlarged or explained. To which also are added, the titles of all the statutes and private acts of Parliament passed by their said Majesties, untill this present year, MDCLXVII. With a table directing to the principal matters of the said statutes. By Tho: Manby of Lincolns-Inn, Esq. 1667 Wing (CD-ROM, 1996) / E898

Wing / 2532:08  Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 I had to laugh when I came across this tract by John Raymond, 17th century author of Folly in Print, or A Book of Rymes (1667). Right away, on the first page, he lets the readers know it really isn't his fault if you don't like his book: "Whoever buyes this Book will say, Next, Raymond then explains to his readers that if they believe what the bookseller says (or sings, as was often the case), it's their own fault if they find they don't like the book after all. "... in Books, where for money or exchange, we take our choice, and in our own Election please our selves; Can you imagine if authors could still add this type of caveat emptor today? Madness! But I'm sure there are many authors today--especially those stung by hurtful reviews--who might wish they could say something like this to their readers: I doe not promise for my Book nor say 'tis good, but here's variety and each man (of his own pallat) is the certain judge: You might like my book, you might not. To each her own!

But what do you think? Have you ever felt deceived about a book?  In seventeenth-century England, the role of servants was far more nuanced and flexible than readers today may realize. Certainly, there was a long-standing patriarchal expectation that the head of a family would maintain a godly and dutiful order over his household. In advice manuals, published letters and sermons, men were repeatedly admonished on how to treat the servants living in their homes. Men were expected to provide food, shelter, religious instruction, and a disciplined hand, much as they were expected to treat their own children and wives. They were not supposed to treat their servants as slaves; indeed, quite the opposite. However, we must always consider the tensions between prescription and practice. Just because the expectations were stated, most certainly does not mean that the expectations were met. For example, in Advice of a father, or, Counsel to a child (1664), men were admonished to:

For this reason, as the last injunction suggests, discretion was particularly important (perhaps because it was not always be realized). The Early English Books are full of tales of servants blackmailing their employers, because they had discovered something the master (or mistress!) would rather have kept hidden (e.g. adultery, gambling debts, infanticide etc). Thus, the same advice manual warns:

This last point suggests that even the lowest servant in his employ should be treated as all the other servants were treated.While the master was expected to rule with a firm hand, he was more like a benevolent monarch than a tyrant:

There's a pragmatic realization here that seems to transcend the ages. If you work someone without letting them "blow off steam," then you run the risk of having unmotivated, even hostile or violent, servants in your household. This holds with the reality of homicide trends in the 17th century: Far more servants killed their masters, than masters killed their servants! This injunction also fits in with the many accounts across the Early English books of servants getting some days off, attending the theatres and fairs, going to market, visiting family, even sharing in merriments with the family. While the author of this piece would mostly likely call for moderation, it's clear that masters did give their servants more freedoms than might be assumed.  Anon. (1664). Advice of a father Anon. (1664). Advice of a father I want to point out one other piece of advice offered in this manual: "Reckon thy servants among thy children; the difference is only in degrees; both make up the economy; thou art the father of the family; a wife servant is better than a foolish child; cast him not off in an old age, when he has spent himself in thy service; a faithful servant does well deserve to be counted among thy friends." There was, without a doubt, a recognition that loyal servants could become more like members of the family over time. In this particular injunction, the master is told not to throw out his servants just because they have become old, but rather to take care of them. The best example I can think of, to help illustrate how a servant could become like a family member over time, is to draw on a 1960s reference: Would the Brady Bunch have thrown out Alice? In my recent novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate, I touch on a lot of these issues. I deliberately placed my protagonist Lucy Campion, in the household of a magistrate, at a time when Enlightened principles were starting to emerge in England. In my story, I deliberately juxtapose the reasoned household of the magistrate, with the less disciplined households that surrounded them. I wanted my magistrate then to be a more Enlightened thinker, more concerned with ideas, than the person who suggested those ideas to him. So he could have listened to and believed in the views of a servant with an intelligent lively mind. Perhaps I gave Lucy too many freedoms, perhaps I didn't. Ultimately, I do not think there is any blanket, all-encompassing way to look at the relationship between masters and servants in 17th century England. Arguably, these attitudes may have changed in the 18th and 19th century (although I doubt there was a monolithic understanding of this relationship even then), but the bottom line is this: The relationship between master and servant in the 17th century was far more nuanced and flexible than is often assumed. This is my story, and I'm sticking to it!  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate.  www.deborahswift.co.uk A few weeks ago, I was fortunate enough to win a free copy of Deborah Swift's atmospheric The Gilded Lily (St. Martin's Griffin, 2012), a historical novel set in Restoration England. She was gracious enough to let me interview her on my blog today. *************************************************** The official synopsis: England 1660 Ella Appleby believes she is destined for better things than slaving as a housemaid and dodging the blows of her drunken father. When her employer dies suddenly, she seizes her chance--taking his valuables and fleeing the countryside with her sister for the golden prospects of London. But London may not be the promised land she expects. Work is hard to find, until Ella takes up with a dashing and dubious gentleman with ties to the London underworld. Meanwhile, her old employer's twin brother is in hot pursuit of the sisters. Set in a London of atmospheric coffee houses, gilded mansions, and shady pawnshops hidden from rich men's view, Deborah Swift's The Gilded Lily is a dazzling novel of historical adventure. **********************************************************************************  What inspired you to write The Gilded Lily? When I originally began The Gilded Lily I was interested in the fact that the ideal of women’s beauty has changed over time. The years when England was suddenly released from the grip of Puritanism seemed an ideal choice to set a novel about beauty and greed. In many ways the 1660s were like the 1960s and at that time there was a great flowering of interest in fashion, the theatre, beautiful women (and men!) and a more laissez-faire lifestyle. The Gilded Lily in the novel is the name of a place where women go to buy perfumes and potions, an enterprise I thought fitted well into this new culture of hedonism. Why did you set your story in 166o? I have always been fascinated by the Restoration – I used to design theatre costumes and did a couple of plays from this period and just loved the whole look. It was a very narrow period of celebration between Puritan rule and the outbreak of the Plague and then the Fire of London in 1665 and 1666. But also London in the 17th century had a much darker face hidden beneath the glamour – it was a much less tolerant society than our own, a magnification of all our vices of bigotry, fear of another’s differences and cruelty to others less fortunate than ourselves. Class structures were more fiercely guarded and it was hard to claw your way upward to a reasonable standard of living. How did you go about researching your story? Did your work as a set and costume designer for the BBC inform your research? I usually spend about six months altogether researching before writing. Most of the research is about ordinary every day objects we take for granted – such as the price of a pair of gloves, or how far a hired horse can gallop in a day. (I spent a lot of time figuring out this conundrum too!-SC). My previous job helps in that I already have research methods in place, and a good basic knowledge of most periods from my experience designing plays. I also have some contacts who are experts in their field who I can ask when I'm stuck! I use books, the internet and museums. Sometimes I need to write to people or interview them for the information I need. For this novel I had to research pawn-broking, wig-making and gunpowder manufacture as well as the apothecary’s ingredients for beauty products. If you had lived in the 1660s, what kind of occupation/station/life could you imagine yourself having? Or put another way, if you wrote yourself into the novel, what kind of character would you be? Well not gunpowder manufacturing or wig-making, that's for sure! Ella and Sadie try these and they are not my idea of fun! Most working women worked cripplingly long hours for little pay so I think I would prefer to be the rich daughter of a man who could afford to send me to The Gilded Lily for my perfumes and potions. On second thoughts, perhaps not, as most of the skin creams contained white lead, mercury, or other dangerous substances. But I did read that there were lots of bookstalls in St Paul's Church, so perhaps I'd be a bookseller! Or even print up my own anonymous chapbooks or pamphlets. What was the most interesting or surprising thing that you learned while writing your novel? One of the most surprising was that the average age of the population of London at that time was very young. Of course people generally died younger, and 85,000 men had been lost in the Civil Wars, and young men took their places. Some men were sitting in Parliament at only 16 years old. Large gangs of youths - displaced from their homes or who had been soldiers in the armies - roamed the city searching for employment. What a place to put two naive country girls! How long did it take you to write The Gilded Lily? How many drafts did it take? It took just over eighteen months, though I had been mulling the idea for longer. I do a rough draft first with only basic research to draft the storyline. Then I research in more depth and the storyline develops and deepens. Sometimes it changes if the research leads me in a different direction. A third draft is about smaller details and characterisation. After that I draft and edit until I think it's ready, which can be about changing whole sections, or about worrying over a single word. What advice would you give to an aspiring novelist? Don't be in too much of a hurry to get the book out there. Editing is vital. In your editing process you can check through each character's scenes for consistency to make sure they are real people. If you are self-publishing make sure you get a professional editor. I'm lucky in that I have a publisher and a great editorial team behind my books. There are many good books being self-published now which could have been GREAT books, given an outside editorial eye. We need great books and great new writers so why settle for anything less? And what are you working on now? My next book is called 'A Divided Inheritance'. It is set in Stuart England and Golden Age Spain and tells the story of a lace trader's daughter who has to travel to Seville to save her beloved home and rescue her inheritance from her firebrand cousin. It will be out in October 2013. It will be hard to wait till October, that's for sure! Thank you, Dee! Deborah can be reached through her website (www.deborahswift.co.uk), Blog (www.deborahswift.blogspot.com)or through twitter @swiftstory.  Watching my five-year old play hopscotch the other day got me wondering--where did this simple game come from anyway? I mean, if you think about it, doesn't HOP SCOTCH sound like it's connected to beer and liquor? Maybe the game came from kids watching adults stumbling out of taverns, under the influence, trying to hop on one foot while picking up stuff they'd dropped, without toppling over. Maybe kids mimicked the grown ups and over time--voila!-- the game of hopscotch emerged. (Okay, I'm writing this entry on a Friday night after a LONG week, so I could be reaching.)  so these guys played hopscotch? Indeed, a quick internet search informed me that no, hopscotch has nothing to do with alcohol (darn it! I thought I was onto something there). Instead, a jillion sites claim that the game actually derived from an ancient Roman military training exercise. Roman soldiers, wearing full body armor, would hop through a hundred-yard field in a precise way, to help improve their footwork in battle. (Cool, hey? Shall I stop here?) Wel-l-l-l, I'm always a bit skeptical of what I read on the internet. Especially since many of these sites seemed to be just parroting the same tidbit over and over without any evidence. And there didn't seem to be any evidence of the term before the seventeenth century. And then I found this fascinating bit of detective work carried out by the "Rogue Classicist." Here, he essentially traced the origins of the hopscotch myth--and yes, it is a myth--to a misunderstanding. Apparently, in 1870 a scholar sharing his findings in an archeology journal made an offhand comment to the effect that some ancient tiles and disks might be 'admirably suited to our modern game of hopscotch.' But someone else misunderstood, and made an erroneous leap--reading a link from ancient times to modern game that was not there. This misunderstanding was picked up, and repeated so many times that eventually it became "fact". Oh, and what's the truth of it all? Hopscotch, originally called "scotch-hop", was a game which probably emerged in seventeenth-century England (although similar games can be found around the world.) First mentioned in the Book of Games in the 1670s, Francis Willughby describes the game of "hopscotchers" in which children play with a little piece of lead on a floor with lines etched--or "scotched"--onto its surface. So, a game. However, if you prefer, we can rewrite the history of hopscotch once again. Just cut and paste my imagined origins of the game--you know, where kids were laughing at drunk grown-ups--and pass it off as fact. What do you think?  So once again, I need to take an extended coffee break to get started on a new novel. In the meantime, I'll leave you with a description of several miracles attributed to coffee, taken from a 1663 dialogue between "Mr. Blackburnt" and "Democritus." I've discussed the virtues of coffee before, but this time I'll focus on the miracles. In this tract, the two men share "several strange, wonderful and miraculous cures (the like never heard of since the creation!)" brought about by drinking coffee. So after drinking coffee: Helsen, a leather-maker in Dalatia, with a consumption in his eye, became so cured that his "pocket was as bare as a bird's arse." (hmmm...a penny to anyone who can explain what that means!) Calego in Spantego, having been troubled with dimness of sight, "broke his fast with a mess of milk-pottage, and the white of his eyes dropped into the dish" (um, gross?) Anna Marina of Rotterdam saw the corn on her lip, which had long been bothering her, drop from her face like a "clean acorn." (Who needs dermatologists when you have coffee!!!) This just goes to show, when I return from my hiatus and much coffee, I'll be seeing better than ever, with no unsightly blemishes! In the meantime, enjoy your coffee!!! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed