I'm so thrilled that my very first short story--The Trial of Madame Pelletier-- was selected for inclusion in Malice Domestic 12: Mystery Most Historical (Wildside Press, 2017). Like my Lucy Campion novels set in 17th century England, this short story stemmed from research I did in graduate school a zillion years ago. (And yeah, that's pretty fun for me to get to use another chunk of this doctoral research in a new way!) I won't say too much about my story other than it features the trial of a presumed poisoner in a small town in France, in 1840. The trial was a cause celebre--a trial of the century--which played out as much in the court of public opinion and in sensationalized newspaper accounts, as it did in the assize court in Limousin. I remember being struck too, not just be the trial itself, but how the woman at the heart of it--the Lady Poisoner--was being tried both as a criminal and as a female. While my story differs dramatically from the trial that inspired it, I did want to convey that same sense of a woman being tried on many levels. Moreover, ever since I read Agatha Christie's Witness for the Prosecution, I have wanted to try my hand at a courtroom drama. So this was such a fun piece for me to write overall. I'm really excited to read the other stories in the volume!!! The selected stories are:

"A One-Pipe Problem" by John Betancourt "The Trial of Madame Pelletier" by Susanna Calkins "Eating Crow" by Carla Coupe "The Lady's Maid Vanishes" by Susan Daly "Judge Lu's Ming Dynasty Case Files-The Unseen Opponent" by P.A. De Voe "Honest John Finds a Way" by Michael Dell "Spirited Death" by Carole Nelson Douglas "The Corpse Candle" by Martin Edwards "Mistress Threadneedle's Quest" by Kathy Lynn Emerson "The Black Hand" by Peter Hayes "Crim Con" by Nancy Herriman "Hand of an Angry God" by KB Inglee "The Barter" by Su Kopil "Tredegar Murders" by Vivian Lawry "The Tragic Death of Mrs. Edna Fogg" by Edith Maxwell "A Butler is Born" by Catriona McPherson "Home Front Homicide" by Liz Milliron "He Done Her Wrong" by Kathryn O'Sullivan "Summons for a Dead Girl" by K.B. Owen "Mr. Nakamura's Garden" by Valerie O Patterson "The Velvet Slippers" by Keenan Powell "The Blackness Before Me" by Mindy Quigley "Death on the Dueling Grounds" by Verena Rose "You Always Hurt the One You Love" by Shawn Reilly Simmons "Night and Fog" by Marcia Talley "The Measured Chest" by Mark Thielman "The Killing Game" by Victoria Thompson "The Cottage" by Charles Todd "The Seven" by Elaine Viets "Strong Enough" by Georgia Wilson

2 Comments

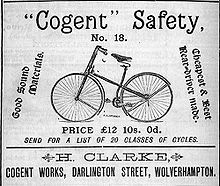

Writers are frequently enjoined to "write what they know," and my guest blogger today has certainly taken that message to heart. Edith Maxwell, author of the the forthcoming historical mystery, Delivering the Truth, features a Quaker midwife in 19th century New England. Edith is a Quaker, has taught childbirth classes, and lives in New England. So I guess she knows what she's talking about!!!  From the official blurb: For Quaker midwife Rose Carroll, life in Amesbury, Massachusetts, provides equal measures of joy and tribulation. She attends to the needs of mothers and newborns even as she mourns the recent death of her sister. Likewise, Rose enjoys the giddy feelings that come from being courted by a handsome doctor, but a suspicious fire and two murders leave her fearing for the well-being of her loved ones. Driven by her desire for safety and justice, Rose Carroll begins asking questions related to the crimes. Consulting with her friends and neighbors―including the famous Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier―Rose draws on her strengths as a counselor and problem solver in trying to bring the perpetrators to light.  Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used In my Quaker Midwife Mysteries, Rose Carroll is a midwife helping pregnant women give birth in the safest way possible - in the 1888 New England mill town of Amesbury. She’s twenty-four, as yet unmarried, and a Quaker. Rose is an independent businesswoman, unconventional both for going about her business on her bicycle and for being a member of the Society of Friends. Quakers have long been known for being unconventional, though, and New England Friends of the era even more so. Rose’s mother works tirelessly for women’s suffrage. Rose’s friend and mentor, the real John Greenleaf Whittier, was an outspoken abolitionist and supported equality among his fellow humans. Rose addresses everyone by their first name regardless of social class or occupation, and speaks using “thee” and “thy” as Quakers did, so she’s used to traveling outside certain norms. She’s also known for her honesty and clean living. Her clients trust her. Although there was a New England Female Medical College, which was a training school for midwives, Rose took the traditional route and apprenticed with Orpha Perkins to learn her trade. When the elderly Orpha retires, Rose takes over her business. The late 1880s is a fascinating period to write about because so much was changing, including the practice of midwifery and medicine. The germ theory of infection was known, so Rose is careful to wash her hands and keep the birthing chamber clean. A new hospital had been built across the river in the bustling seaport town of Newburyport only a few years earlier. Cesarean sections were done, but it was still a very risky procedure. And male doctors were starting to do deliveries, practicing obstetrics. I read that this practice increased in part because women working in factories were living away from their female relatives who would normally support them through the birth and postpartum period. The husband of one of Rose’s clients insists that his baby be delivered by a male doctor, but most of Rose’s pregnant clients much prefer having a woman attend them. I also read an account of a Massachusetts midwife being sued in 1905 for practicing medicine without a license. I haven’t heard of such accusations twenty years earlier, however. Of course, being a midwife makes Rose a perfect protagonist. She can go places no male police officer can – women’s bed chambers – and hears secrets the detective isn’t privy to, both during labor and at client visits. I know in earlier times midwives had a obligation to extract information from unwed mothers about the father of the baby and report him to the authorities, but I haven’t been able to unearth whether that practice still stood at the end of the nineteenth century. (See Sam Thomas' excellent post on the role of midwives in 17th century England, for example. -SC)  Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission I’m delighted to follow Rose around the streets of my town where many of the buildings of the late 1880s still stand, including the Friends Meetinghouse where she and Whittier worship, and write down her adventures.  Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries (Midnight Ink) and the Local Foods Mysteries, the Country Store Mysteries (as Maddie Day), and the Lauren Rousseau Mysteries (as Tace Baker), as well as award-winning short crime fiction. Her short story, “A Questionable Death,” is nominated for a 2016 Agatha Award for Best Short Story. The tale features the 1888 setting and characters from her Quaker Midwife Mysteries series, which debuts with Delivering the Truth on April 8, 2016. Maxwell is Vice-President of Sisters in Crime New England and Clerk of Amesbury Friends Meeting. She lives north of Boston with her beau and three cats, and blogs with the other Wicked Cozy Authors. You can find her on Facebook, @edithmaxwell, on Pinterest, and at her web site, edithmaxwell.com. Want to know more about the original Quakers from 17th century England? Check out my discussion of the political activities and writing of Quaker women. Or this post on their last dying speeches.

I received a query from a reader yesterday that gets at the many meddlesome and troublesome questions that writers of British historical fiction inevitably face--How do nobles address each other? "...I just wanted to know: if the oldest daughter of an earl was going to soon be marrying the oldest son of another earl, how would they address one another? The setting is 1860s London, if this helps answer my question. I have read many websites and guide-books that explain how the peerage would be addressed by various people in various situations, but I am having trouble finding information about two people, both children of earls, who are engaged to be married. Would they be more casual with one another? Or would it be inappropriate to address one another without their appropriate title? Your help would be greatly appreciated. Thank you." --Maryam. This is indeed a tricky question. I know something about the forms of address in 17th century England, but I didn't want to assume what was common or expected in the 1660s would be the same 200 years later, in the 1860s. So I threw this question out to the lovely and talented Sleuths in Time, who have spent a lot more time than I have thinking about this question.

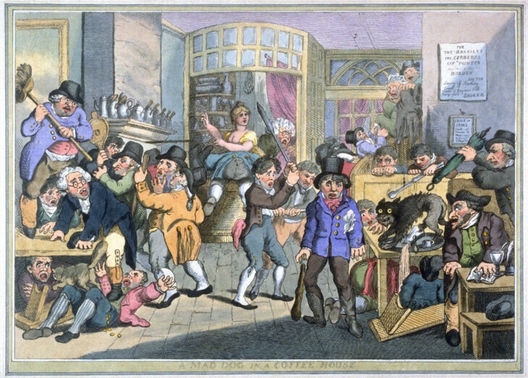

So, first, the basics. According to Tessa Arlen: "The eldest daughter of an earl would be called Lady Susan; that would be the extent of her title until she marries. If she were to marry an ordinary man she would be called Lady Susan and then his surname: Lady Susan Blogs for example. The eldest son of an earl might be given an honorary title of his father's of a lower rank this would be given to him until he inherited his father's title. For example, his father who is Roger Parker, Earl of Bainbridge might bestow the honorary title of viscount on his eldest son. So the son's name and title would then be Denis Parker, the Viscount Lord Winslow. It is also important to remember that the Earl of Bainbridge would have a family name, in this case Parker." This seems pretty straightforward so far, right? Tessa continues: "I can't imagine why this young couple would call one anything other than by the first names when they were alone together. And if they are English the usual terms of endearment! If they were together out in society Lady Susan would be referred to as the Vicountess Lady Winslow and her husband would be the Viscount Lord Winslow and they would be announced as Lord and Lady Winslow. When Lord Winslow's father dies and he inherits the earldom he will become the next Earl of Bainbridge - and be called Lord Bainbridge and his wife would become the Countess of Bainbridge. The order of precedence can be very confusing - even for Brits. So tell your friend to follow this pattern and she will sound like she knows what she is talking about!" Excellent advice! Alyssa Maxwell also commented: "Sometimes the son and heir would be called by his courtesy title without Lord in front of it, as in Brideshead or Bridey as friends and family called him in the book." She also directed us to Jo Beverley's Guide to English Titles in the 18th and 19th centuries, a very helpful resource! As Anna Lee Huber further notes: "In the case of an earl, he usually does have a lesser title (viscount or baron) he can grant his eldest son as a courtesy, but it's also possible he doesn't. (Author's choice since it's fiction.) In that case he would be called Mr. Parker by his fiancé in public, Denis in private. The rules for daughters & sons of earls are slightly different. Daughters of dukes, marquesses, & earls receive the honorary Lady before their first name. Only sons of dukes & marquesses receive the honorary Lord before their first name." And to round us out, Ashley Weaver says, "I have always found [Laura Chinet's] site really useful for reference. She has little charts and everything!" [I will say, however, that what Laura Chinet describes for the 18th and 19th century may be different from 17th century conventions. In my research, I have seen many letters between family members that use endearments, like "My dearest Anne." So it stands to reason that if they use such intimacies in written letters, they would do the same in private conversations. There is a formalization of speech and manners that happened in the mid 18th century that was not as pervasive in earlier centuries-SC]. Ultimately, in my opinion, this comes down to an accuracy vs authenticity kind of question. I think writers of historical fiction should try their best to be as reasonably accurate as possible, but ultimately their focus should be on telling the best story possible, without jarring the reader. A while back someone gave me a book on writing, which contained a number of random quotes by writers. As a historian, I am sometimes frustrated when presented with quotes that have been detached from their original context and passed off as inspirational or profound. So as I was flipping through the book, I came across this one that made me sit up and take notice: "The author must keep his mouth shut when his work starts to speak." -Friedrich Nietzsche  So without knowing anything about Nietzsche, I might interpret this as a humble phrase. Let your work speak for itself. Perhaps, it is a warning. You must let others critique your work as they will, once it is out in the world. Do not answer your critics. Or maybe it is just a reminder to writers. Do not edit or self-censor as you write, but allow your work to emerge in the world in its most full and beautiful form. I assume because the quote was included in this writing book, and is oft-repeated (again, with no context) on many writing sites, that this admonition is seen as a virtue. Do words have meaning of themselves? Do they live, and change with the times? Or do they need to be ever-framed by the context with which they were first uttered? Consider the source of this quote. Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche was a nineteenth-century German philosopher, philologist and poet, among other things. Such as being a megalomaniac. And a syphilis-riddled man who spoke frequently of his own genius. A man whose work inspired both Nazis and Fascists alike. Altogether, an intriguing--if tortured--soul. So what did he mean when he said this? As I indicated, it's very difficult to identify the source of this quote, so for all I know it is completely inaccurate and has just been repeated ad nauseam. Some digging for the past hour (which is about all the time I have to devote to this quest) has yielded little more context, except that I think, but can not be sure, that the quote appeared in the second edition of Nietzsche's first published book The Birth of Tragedy, in a new section called "Attempt at a Self-Criticism" (1888). Rather than being a true self-criticism, however, the statement is widely viewed by scholars as a means for Nietzsche to clarify his earlier views, and to impose his later thinking onto his earlier work. Such a revision could be construed as more arrogant than humble ("See how brilliant I was, even when I was a young man?") This additional context, to my mind, sheds a different interpretation on the quote. Should we just make sense of words ourselves? Or does the larger context matter? While there's a pleasing democracy about the idea that we can all interpret words for ourselves, for my part, I think, understanding the larger context almost always offers a more full and interpretation of words. But what do you think? [P.S. I also find it amusing how often the above quote by Nietzsche is used by authors, when it turns out that he actually did write "Rules for Writers" that are NEVER EVER quoted. Such as this gem: "Be careful with periods! Only those people who also have long duration of breath while speaking are entitled to periods. With most people, the period is a matter of affectation." Rich stuff indeed!] Image: Lou Andreas-Salomé, Paul Rée and Friedrich Nietzsche (1882) I'm joined on my blog today by award-winning author, Anna Lee Huber. I had the pleasure of meeting this talented writer, last year at Bouchercon, during a signing for new authors. On Saturday September 14, Anna and I will be doing a joint signing at Centuries and Sleuths in Forest Park, IL at 11:00. Hope to see you there! **********************************************************************************  Love the title of Anna's 2nd book! Love the title of Anna's 2nd book! Scotland, 1830. Lady Kiera Darby is no stranger to intrigue-in fact, it seems to follow wherever she goes. After her foray into murder investigation, Kiera must journey to Edinburgh with her family so that her pregnant sister can be close to proper medical care. But the city is full of many things Kiera isn't quite ready to face: the society ladies keen on judging her, her fellow investigator-and romantic entanglement-Sebastian Gage, and ultimately, another deadly mystery. Kiera's old friend Michael Dalmay is about to be married, but the arrival of his older brother-and Kiera's childhood art tutor-William, has thrown everything into chaos. For ten years Will has been missing, committed to an insane asylum by his own father. Kiera is sympathetic to her mentor's plight, especially when rumors swirl about a local girl gone missing. Now Kiera must once again employ her knowledge of the macabre and join forces with Gage in order to prove the innocence of a beloved family friend-and save the marriage of another... **********************************************************************************  the talented Anna Lee Huber the talented Anna Lee Huber Thanks for joining us today! Mortal Arts, the second in your series featuring Lady Kiera Darby, is set in Scotland in 1830. What made you choose this particular place and time? When I decided to write a historical mystery series with a heroine who has some knowledge of anatomy, I knew 1830 would be the perfect time period. It’s just after the trial of Burke and Hare, two body snatchers-turned-murderers, which plays into the public’s fear of Kiera once news of her involvement with her late husband’s dissections comes to light, and it’s just a few years before the Anatomy Act of 1832. Not to mention all of the other reforms being made with the Catholic Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832, the beginnings of the building of railroads, the ramping up of industrialization. It’s a very interesting period. Lots of conflict. Could you also tell us a little about what inspired you? I have difficulty pinpointing exactly what first inspired me to write the Lady Darby novels. I was very deliberate in choosing the genre, and I crafted Kiera’s backstory to give her the investigative skills I wanted her to have, and the rest of her history was created from the consequences of that. The plot of Book 1, The Anatomist’s Wife, even grew from that. I chose to set it in the Scottish Highlands because I needed an isolated location. I tell people that Kiera feels like she’s always been there, in the back of my mind, and I think it’s true. From the very first, even before I knew who she was, I could hear her voice very clearly in my writing. So perhaps that’s why I have trouble deciding on the inspiration. It happened when I wasn’t paying attention. Lady Darby has been described as “an unusual and romantic heroine.” What makes her so unusual? Is she someone you would want to be friends with? First of all, she’s a gifted portrait artist, determined to pursue her art—something not very common for a woman in her time. She has the ability to lose herself in her art, and to see to the heart of the person she is painting, which often unnerves people, even as it makes her portraits special. Even more startling, she was forced to assist her late husband, who was a famous anatomist and surgeon to royalty, with his dissections, sketching them because he did not wish to split the credit for his anatomy textbook with an illustrator. So she has knowledge of anatomy that she’s unwillingly collected. When the scandal broke over her involvement with her husband’s work, society and the general public vilified her, concocting all sorts of gruesome rumors about her. Her standoffish demeanor and quiet reserve do not help matters. She is not comfortable in society or large gatherings, but she is fiercely loyal to those she cares about. She is intelligent, insightful, and witty. I would definitely want her for my friend. Tell us about Sebastian Gage, Lady Darby’s romantic interest. Can you give us a hint as to which actor you would cast to portray him in a film version of the novel? Sebastian Gage is a gentleman inquiry agent who works with his father to help the upper class with their sticky situations. He is charming and extremely attractive, and a bit of a golden boy who is much in demand at society’s gatherings. He also has a reputation as being a bit of a rakehell, but Kiera soon begins to doubt that persona. His true self is somewhat a mystery and he does not share himself easily, which frustrates Kiera to no end. If I got to cast Gage, I would choose someone like Rupert Penry-Jones. He was fabulous as Captain Wentworth in the BBC version of Jane Austen’s Persuasion. (Hmmm...me likes!)  Anna's award-winning first book Anna's award-winning first book What was your favorite part of writing Mortal Arts? My favorite part of writing Mortal Arts was getting to spend more time with the characters I’d created in The Anatomist’s Wife and take them further along on their journey. I love it when they surprise me. Least favorite? My least favorite part was struggling with the doubts and crisis of confidence I had in myself. I had quite a lot of trouble with “imposter syndrome.” There’s this fear, irrational as it may be, that you fooled everyone the first time around. That you truly can’t write. And now you’ll be found out. I constantly had to shore up my belief in myself as a writer. How did writing Mortal Arts compare to writing your debut novel, The Anatomist’s Wife? What was similar about the process? Different? Writing Mortal Arts was my first attempt at writing a sequel, and it was also my first time writing to a publisher’s deadline, both of which added pressure. In one sense it was harder, feeling all of that added pressure, fearing I wouldn’t be able to write another good book. On the other hand, it was also easier. The book was already sold, so all of those worries I felt that I would never be published were no longer there. I’d achieved what I wanted, and that was a huge relief. I had to do more plotting with Mortal Arts. However, I already knew many of the characters, so that was less work. When did you first know you wanted to be a writer? Do you have any manuscripts buried in a drawer somewhere? I first started writing in elementary school, and I have a box full of old stories I wrote then. I moved away from it in high school and then college, but returned to it again after graduation. I wrote four unpublished manuscripts before The Anatomist’s Wife sold. Some of those manuscripts may someday see the light of day, after extensive edits. But others will remain buried on my computer, as they should be. What advice do you have for aspiring writers? First and foremost, never give up. I’m a testament to the power of perseverance. I always say, the only way you are guaranteed not to succeed is if you give up. Second, write, write, write. It’s absolutely the best way to learn. And then find a critique group or a few trusted people who know what they’re doing to help you make your writing better. What’s next? The third Lady Darby novel, A Grave Matter, is scheduled for release in July 2014. I’m finishing that up, and then I want to work on a side project I started a while ago. It’s more of a straight Gothic suspense novel set in Regency England, and I hope to have that polished and ready to go by the end of the year. If it's anything like the first two, it will be another winner! Congrats on your success! ********************************************************************************** Anna Lee Huber is the award-winning author of the Lady Darby historical mystery series. Her debut, The Anatomist’s Wife, has won and been nominated for numerous awards, including two 2013 RITA® Awards and a 2013 Daphne du Maurier Award. Her second novel, Mortal Arts, released September 3rd. She was born and raised in a small town in Ohio, and graduated from Lipscomb University in Nashville, TN with a degree in music and a minor in psychology. She currently lives in Indiana, and enjoys reading, singing, traveling and spending time with her family. Visit her at www.annaleehuber.com.  English: "A Mad Dog in a Coffee-House" (1809) by Rowlandson, showing a rabid dog terrorizing a coffee house in 18th century England (possibly Garrison's or Jonathan's, near the Exchange) Such chaos! Such mayhem! Okay, that's all I've got. There's a caricature in here somewhere, but I'd have to do a little research to figure it out. Unfortunately, I don't have the time... Once again, I need to take an extended coffee break, aka temporary blog hiatus. I knew I was having a minor problem when I kept starting posts with no time to finish them.

So I'll be finishing gallons of coffee in my attempt to balance work, teaching and writing...all while doing publicity stuff for A Murder at Rosamund's Gate...did I mention that it's coming out April 23? :-) But I'll be back soon! In the meantime, I'll leave you with the above image as a writing prompt. What's going on here? What schemes are afoot? Or most simply of all, Who let the dog in? Happy writing!  ********************************************** A QUICK EXPLANATION OF THE IMAGE!!! I just had to research the meaning behind this image (despite being on my self-imposed blog hiatus). In doing so, I came across this interesting work by Joseph Grego, who wrote extensively about Rowlandson in 1922. He offers an interesting explanation of the painting that gets at the shifting economic concerns at the time. In his own inimitable words, Grego writes: "March 20, 1809. The advent of a nondescript animal, … assumed to be a ferocious mad dog, has produced the utmost terror and confusion amongst the grave frequenters of a mercantile coffee-house… All the city brokers, and pillars of change found therein are seared out of their sober senses; some…are paralyzed with fear; others are trying to creep under the tables; a few are seeking escape by the door which they are effectually blocking; and groups of affrighted fugitives are endeavoring to gain the refuge of the staircase….Comfortable citizens are thrown on their backs, like turtles, and trodden on, while the pressure of viler bodies above is expressing a stream of specie from the well-filled pockets of the overthrown…." So what does all this mean? Essentially, something seemingly innocuous has pervaded the economy, and it will cause mayhem. The explanation for this mayhem apparently can be found on the advertisment (notice) stuck on the back wall, which offers an important piece of shipping intelligence. The notice warns 'lay off Barking Creek," the location of a large fishing fleet in London. Barking Creek...rabid dog, get it? (but now back to writing!)  Mary Amelia Ingalls (1865-1928) Until yesterday, if you had asked me what I knew about scarlet fever, I would have been able to tell you two things: A lot of people seemed to have contracted it in the nineteenth century, and in severe cases, a person could die, or at least go blind. My evidence? Well, Laura Ingalls Wilder of "Little House" fame attributed her sister Mary's blindness to scarlet fever. I, for sure, took this diagnosis at face value. Why wouldn't I? However, as it turns out, Mary probably suffered from viral meningoencephalitis. In a recent Pediatrics article, Dr. Beth Tarini and some colleagues reported their reassessment of Mary's condition, having spent years pouring over Laura's letters and other documents which alluded to Mary's symptoms. Even though Mary had indeed contracted the disease as a child--in both the TV show and the book, we were infomed that "her eyes had been weakened as a child"--other symptoms were more telling. She went blind as a teenager, in 1879. Half her face had apparently been paralyzed, along with her eye muscles. Most telling of all, Laura later refers to Mary's "spinal sickness" in a letter to her daughter Rose. In 1881, Mary went to the Iowa Braille and Sight Saving School.  Helen Keller, 1880-1968 Interestingly, a thousand miles away in Alabama, Helen Keller--an infant-- had also just contracted a disease that caused her to lose her sight and vision. Like Mary Ingalls, her condition was also attributed to scarlet fever. Physicians now suspect, however, meningitis was the more likely culprit. Was the assumption of scarlet fever simply a misdiagnosis? In the case of Helen Keller, this is quite possible. In the case of Mary, no. Dr. Tarini's team concluded that the family was aware of Mary's true disease, but that Laura had deliberately obscured the nature of her sister's condition when she discussed it in her books. Why would Laura have changed her sister's disease? Dr. Tarini conjectured that scarlet fever, being a common malady, would have been more relatable to the author's audience. There's something to that hypothesis, for sure. However, at the end of the nineteenth century, there was a real stigma associated with "brain fever," a catch-all term for neural sicknesses like meningoecephaliti and meningitis). After all, this was the era of both the rise of psychology and neurology, and the accompanying classification of mental disorders and illnesses. So Laura's rewriting of her sister's history was likely because scarlet fever was more palatable, not just more relatable. Laura is certainly not the first person to hide her family's secrets, or to rewrite her narrative. The tragedy of her own husband--Almonzo--is another example of how she reconstructed her past. But perhaps that's the greatest feat of a storyteller. Telling the story we want to hear, not what really happened. In this case, however, Laura's retelling has probably caused generations of people to associate scarlet fever with blindness, which is certainly incorrect. Yet another reason to constantly question what we read; to question what we know to be true. But what do you think?  17th c. detective of poisons A few weeks ago, I wrote about the first female literary sleuths, and since then I've since been wondering about the real first "detectives." I don't mean just any investigators of criminal activity, for surely, those have existed since time immemorial. But I was curious about when the term "detective" emerged as a recognizable title and/or occupation. The word does appear in the Early English Books Online as early as 1634. However, the word detective was not used as a noun, but rather as a verb, referring to the process of detecting. Specifically, the "famous chirugion [surgeon] Ambrose Parey" detective the effects of deadly poisons on the human body. Turning to my trusty Oxford Etymological Dictionary, I found that as a noun, "detective" was not used before before 1843. According to the Chambers Edinburgh Journal, "Intelligent men have been recently selected to form a body called the ‘detective police’‥at times the detective policeman attires himself in the dress of ordinary individuals." (12: 54). The word was later referenced in Willis' discussion of modern thief-taking in 1850: "To each division of the Force is attached two officers, who are denominated ‘detectives’" (C. Dickens, Househ. Words 13 July 368/1). Prior to 1850, those conducting investigations might have been called a searcher (1382), intracer (?a1475), inquisitor (?1504), inseer (1532), theif taker (1535) (my favorite, and the one I use!), peruser (1549) investigator (1552), tracer (1552), scrutineer (1557), examiner (1561), revisitor (1594), researcher (1615), examinant (1620), indagator (1620) (that's a great one!), ferret (1629), (another great one!), pryer (1674A), probator (1691), disquisitor (1766), grubber (1776), prober (1777), plant (1812), grubbler (1813), and plain clothes (1822). After 1850, additional colorful slang variants were used: Plainsclothesman (1856), mouser (1863), sleuth (1872), tec (1879), dee (1882) (shortened version of detective), sleuth-hound (1890), split (1891) (evolution of informer, turning against another person), hawkshaw (1903) (a character in a play), busy (1904), gumshoe (1906), (from the quiet stealthy shoes detectives began to adopt), dick (1908) (comes from a colloquial collapsing of 'detective'), and Richard (1914) (the common surname for nickname Dick). (Most of these expressions, it should be noted, came from criminal slang) And the first real person to be called detective? Well, it's hard to say...  In literature, the first detective is usually considered to be August Dupine in Edgar Allen Poe's Murder in the Rue Morgue (1841) (although I don't think he's referred to in the original version as a detective). Paul Collins, an associate professor at Portland State, a.k.a. the literary detective, has made the case for Charles Felix's detective in Velvet Lawn (1862) as the first of the genre. (On my list to read!). Others have argued for Inspector Buckett from Charles Dickens' Bleak House (1853), who may well have been based on a real private investigator that Dickens knew.  "We never sleep?!" Hey, that's my motto These works, demonstrating the emerging professionalism of detectives (or inspectors), clearly were influenced by larger nineteenth-century trends--most notably the ongoing reform efforts (which called for systematic, often covert, investigations into the corrupted and abusive practices found in factories, prisons, schools, hospitals, etc). Something else accompanied that change. As an investigator, the nineteenth-century detective was trying to systematically solve problems, using science to find solutions to the puzzles that plagued society. The "new" detectives were adopting a scientific, logical quality to the process of capturing criminals. The first known (and organized) private detective agency emerged in France in 1833. This occurred under the auspices of Eugène François Vidocq, a soldier turned privateer, who lived much of his early life on the run from from the law. (Apparently, Victor Hugo was so impressed with Vidocq that he based not one, but two, of his most important characters in Les Miserables--both Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert--on the man). Officially, however, at least in the U.S., Allen Pinkerton, a transplant from Glasgow, Scotland became Chicago's first detective in 1849. Soon after, he set up his famous Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the 1850s. Ultimately, this professionalization of the detective--with its' new emphasis on applying science, logic and technology to catching criminals--gradually reshaped the image of the investigator from "thief taker" to puzzle solver. These trends seem to have substantially influenced at least the first few generations of literary detectives, maybe more. Enter Sherlock, Poirot and all those who rely on "their little grey cells" to solve mysteries... (I do think the recent trend of paranormal crime solvers indicates the inevitable backlash, however, but that's another story). What do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed