Probably one of the most frequently asked questions I get from people seeking to write historical fiction is this: How much research should I include in my historical novel? And my reply, which may sound more flippant than I intend, is just this: Enough to tell the story. I've written elsewhere about balancing historical accuracy and authenticity. So, I thought today I'd given an example of how I seek to have my characters interact with historical details, hopefully without just dumping my research on my readers. I could have picked any passage, but in honor of Easter, I picked an excerpt from my forthcoming novel, A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET. In this, scene Master Aubrey has just returned from selling pamphlets (unsuccessfully) on Maundy Thursday, (known in other parts of the world as "Holy Thursday.") There were a couple of factual details about Easter that I wanted to bring up in the scene. First, since the Middle Ages, there was a tradition in England that on Maundy Thursday, the monarch would give money to the poor and wash the feet of twelve poor people. [Indeed, while the etymology is not certain, the word "Maundy" may have come from the Latin world mendicare ("to beg.")] But we know from the diarist Samuel Pepys, in 1667, King Charles II opted against the practice that year, asking the Bishop of London to do it for him. Second, there had been an ongoing debate about the moveable date of Easter--some scholars of the time insisted that the date should be the same each year, similar to how Christmas was always on December 25. Third, in general, I wanted to allude to the fact that England was on a different calendar (the Julian Calendar) than Catholic nations like France and Italy, which had adopted the calendar created by Pope Gregory (the Gregorian Calendar). I couldn't use all the research I had at my fingertips, but I tried to work in a few of the more salient points within their trade as the printers and sellers of books. So you can see what details I managed to include...  John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 John Pell, Easter not mis-timed (1664) Wing / 395:11 Master Aubrey laid his pack down. “I sold a few. I went to Whitehall to see the King wash the feet of the poor people, but the Bishop of London did it on his behalf.” The printer seemed a bit disgruntled. It had long been the custom for the monarchs of England to wash the feet of twelve men and women, as Jesus had washed the feet of the Apostles before the Last Supper. Having the Bishop of London take on the task instead of the king clearly irked him. Sometimes Lucy suspected the printer had Leveller sensibilities and liked it when the royals took on more mundane responsibilities. “Which pieces did you bring?” Lucy asked, changing the subject. In truth, she was always intrigued to know how the packs got decided. Master Aubrey had a knack for knowing what to sell to attract a crowd that she desperately hoped to learn for herself one day. “Could not very well sell murder ballads and monstrous births on Maundy Thursday, hey? Brought along John Booker’s Tractatus paschalis and John Pell’s Easter Not Mis-Timed. Too many of them, it seems. Only the sinners’ journeys, like the one you wrote about that Quaker, sold today.” He kicked the still-full bag, looking in that moment a bit like Lach, causing Lucy to hide a smile. A rare miss for Master Aubrey. Most people did not care how the date of the moveable holy day was affixed in the almanacs each year. Nor did they care why Catholic nations celebrated Easter and Christmas on different days than they did in England. I'm sure some readers might think that I have provided too much detail here, and other people think I have not offered enough. But, for me, this was "enough to tell the story."

0 Comments

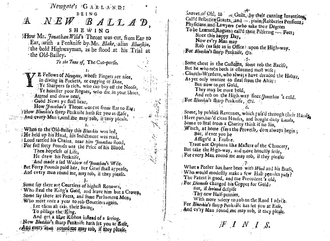

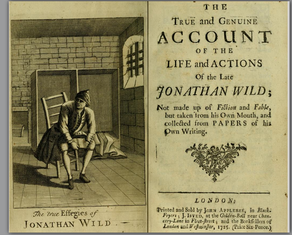

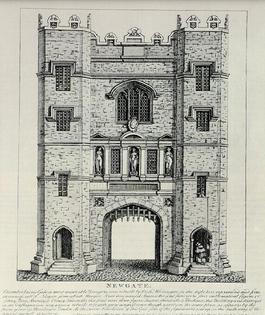

Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Star Wars "The Charred Remains" version :-( Every morning, when I check my email, I'm reminded of a funny (funny-weird, not funny-humorous) thing about book titles. Because I have a daily Google alert on my titles, I get a little summary about how they have used been used on the internet. For my first novel A Murder at Rosamund's Gate and for my third novel, The Masque of a Murderer, I get alerts that actually pertain to my book. But for my second book, From the Charred Remains, I am treated to all sorts of terrible and strange news stories--usually house fires--of things or people being found after a fire (this gem to the right is one of the better things that's come this way). Literally, this illustrates the dark side of book titles. There are terrible things that happen in the world--beyond what happened on the mythical Tatooine--and every day those come to my inbox because of how I titled my book. I shouldn't be surprised--after all, the premise of my book is that a body has been found in a barrel outside the Cheshire Cheese after the Great Fire has devastated much of London. So as I sort though new titles for my fourth book--the soon to be renamed Stranger on the Bridge--I find myself avoiding titles that reporters might use to describe particularly grisly stuff. It's ironic really. The title of my first book didn't make it through marketing, but it was originally called Monster at the Gate. I thought the concept of monster fit well with my time period, but that title was deemed too harsh and supernatural. I can only imagine the kinds of Google hits I would have gotten, had I kept that title. The original title of my third book, Whispers of a Dying Man, didn't make it past my own internal scrutiny. Bleagh. Glad I changed that one. The Masque of a Murderer is a much better title. But From the Charred Remains sailed through easily. I still like the title, but I'm still a bit wary when I see what Google has sent me. Now, I'm still pondering the title of my fourth book. Stranger on the Bridge just isn't resonating for me. So at New Year's, after describing the premise, I asked a bunch of my friends to all put single words (nouns and adjectives) into a hat. Then we all picked three or four slips of paper and formed titles. The best of this admittedly drunken endeavor was Across the Misty Divide. Probably won't go over either (sorry Steve!). Maybe the parlor game method of naming books is not the best method. So hopefully something connects soon!!! I'll keep you posted!  Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 I had to laugh when I came across this tract by John Raymond, 17th century author of Folly in Print, or A Book of Rymes (1667). Right away, on the first page, he lets the readers know it really isn't his fault if you don't like his book: "Whoever buyes this Book will say, Next, Raymond then explains to his readers that if they believe what the bookseller says (or sings, as was often the case), it's their own fault if they find they don't like the book after all. "... in Books, where for money or exchange, we take our choice, and in our own Election please our selves; Can you imagine if authors could still add this type of caveat emptor today? Madness! But I'm sure there are many authors today--especially those stung by hurtful reviews--who might wish they could say something like this to their readers: I doe not promise for my Book nor say 'tis good, but here's variety and each man (of his own pallat) is the certain judge: You might like my book, you might not. To each her own!

But what do you think? Have you ever felt deceived about a book?  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. What's going on here?

You'll have to check out my post on A Bloody Good Read: Where Writers and Readers of Mysteries Talk Shop to find out!!!  1631 STC /1476:06 Riddles, jests and other merriments always sold well in seventeenth-century England. Then, as now, people enjoyed a good laugh--being surrounded by plague, terrible sickness, fire, Puritans, etc may have had something to do with that! When I came across A Book of Merrie Riddles--claimed to be "very delightful for youth to try their wits"--I couldn't resist offering a few to YOU. Let's see what you make of these seventeenth-century jests. First, I'll give you few questions with solutions. Then, I'll give you a few without; see what you come up with. Question: I wound the heart and please the eye. Tell me what I am, by and by. Solution: Beauty. Question: When I did live, then was I dumb, and yield no harmony: But being dead, I do afford most pleasant melody. Solution: Any musical instrument made of wood. Easy, right? Of course there are a few a little more inscrutable today: Question: Who wears his end about his middle once in his time? (I would let you figure out this one, but it's pretty contextually situated.) Solution: A thief whose arms are tied with the halter, wherewith he shall be executed. Hmmm.... So here are a few more...what do you think are the solutions? Question 1: I do walk, yet I do not go. I do drink, yet no thirst lack; I do eat, yet do not feed; I do wake, yet no work make. What am I? And another: Question 2: I was not, I am not, I shall not be, yet I do walk as men do see. What am I? ********************************************************** Let me know: Are you as smart as a 17th century youth? I'll post the answers soon..... *********SPOILERS!!! Solutions ahead!!!***************

I figure that's sufficient space, if you're really concerned. Question 1: so, so, SO LAME. The solution is "Someone moving about in a dream." Question 2: so, so, so, SO, SO, SO LAME! (or fiendishly clever, you decide). The solution is "A person with the surname of 'Not'." As in Susie Not. NOT!!!  After Newgate burned down, then what? When I wrote the first draft of From the Charred Remains, I focused mainly on getting the story worked out--finding the heart and shape of my tale. I didn't stress too much over language, description, and dialogue on the first go-round--I figured I could elevate my prose later. As for historical details, I frequently had to make my best educated guess about what might have been true in those first weeks after the Great Fire of London (September 1666)...and move on. Now as I work through draft two, I'm doing the hard--I mean fun--part: Fixing and double-checking all the historical details. I've already mentioned two of my recent questions (How plausible was the stated death toll of the Great Fire of London?) and (How far could a horse travel in the seventeenth-century anyway?), but here are a few other things that I've pondered: Since my heroine is now a printer's apprentice (yes, unusually so!) I had to figure out a lot of specifics about the early booksellers and their trade. So I wondered, for example, how did a seventeenth-century printing press operate? As it turns out, the press operated in a remarkably gendered way--parts of the machine were referred to as "female blocks," which had to connect with "male blocks." The interconnected parts were supposed to work together harmoniously, but on occasion--usually when the female "leaked"--the whole press might stop working. (Naturally, the female part was to blame!) And another question: Since three of the largest prisons--Newgate, Fleet, and Bridewell--were all destroyed in the Great Fire, where were criminals held? I had to make my best guess on this one. There were other prisons of course: Gatehouse prison in Westminster, the White Lion prison, the Tower, and my favorite, the Clink in Southwark. But I decided to invent my own makeshift jail--after all, in those chaotic days after the Great Fire, order had to be regained quickly, and it stands to reason that royal and civil authorities might have wanted lawless behavior contained as quickly as possible. I couldn't find evidence to the contrary, so an old chandler's shop became a temporary jail. And were criminals still being hanged at the Tyburn tree immediately after the Fire? Executions resumed quickly after the Fire, conducted as they had been since the twelfth century, in the village of Tyburn (now Marble Arch in London). Prisoners were progressed by cart, from jail to the "hanging" tree, parading through the streets--often praying, preaching, repenting or depending on their personality, even swapping jokes with the spectators. Usually they stopped at a tavern for one last drink along the way, before being forced to do the "Tyburn jig," as Londoners cheerfully called execution by hanging. Of course, I also looked up countless other details...Who used acrostics and anagrams to convey messages? What secrets might be conveyed in a family emblem? And most significantly of all: What happened when the first pineapple arrived in London? Ah-h-h, but I can't tell you about these answers....I'd be giving too much away about Book 2!!! I don't really have a question for you to answer, so I'll just end with a maniacal laugh... MWAH HA HA HA HA....!!!  Early English Books Wing / B4610 Is bookselling today so very different than it was a few hundred years ago? Certainly, some similarities can be found. For example, an author could write a piece and see it published and distributed the very next day if he or she chose. Some printers would pay the authors for particularly compelling (read: sellable!) chapbooks, ballads, broadsides and woodcuts. Authors might also have paid a printer to see their work published. However, there was one notable difference: Early modern booksellers and chapmen might chant or 'sing' their wares, in order to garner reader interest and directly engage their audiences. (Unlike today where authors read their own books. So fun, though, to think of modern publishing executives standing on street corners, singing their clients' books!). Authors often wrote their pennypieces, knowing they would be read out loud. So, take a typical seventeenth-century woodcut. A Brief Narrative of a Strange and Wonderful Old Woman that hath a Pair of Horns growing upon her Head (London, 1676). Having identified a busy intersection near a market, church or tavern, the bookseller would call out to passers-by: "You that love Wonders to behold Here you may of a Wonder read. The strangest that was ever seen or told, A Woman with Horns upon her Head." Horns upon her head? Surely a crowd would gather. The bookseller would continue, acknowledging that the tale about to be told was completely preposterous. "It may be, upon the first View of the Title of this short Relation, thou wilt throw it down with all the carelessness imaginable, supposing it to be but an idle and impertinent Fiction..." But the author's stated goal was to make the incredible seem credible, and the bookseller needed to convey that in order to sell the piece. Evidence, eye-witness testimony, whatever worked: "Take but a Walk to the Swan in the Strand, near Charing-Cross, and there thou mayest satisfie thy Curiosity, and be able to tell the World whether this following Narration be truth or invention." And a few more specifics intended to help the reader/listener connect and visualize the story: The 76 year old woman had been born and bred in "the parish of Shotwick in Cheshire." Married for 35 years before being widowed, she had lived a "spotless and unblameable life," helping her neighbors in her role as a midwife. The groundwork laid, now the bookseller might offer some more sensational details. How did the woman's horns first emerge? "This strange and stupendious[sic] Effect began first from a Soreness in that place where now the Horns grow, which (as 'tis thought) was occasioned by wearing a straight Hat." Would the audience believe that? While some authors might have portrayed this hapless woman as a monster, this one took a more sympathetic view. Good booksellers might have changed their tone here, to cull the sympathies of their listeners.... "This Soreness continued Twenty Years, in which time it miserably afflicted this good Woman, and ripened gradually unto a Wenn near the bigness of a large Hen Egg... After which time it was, by a strange operation of Nature, changed into Horns, which are in shew and substance much like a Ramms Horns, solid and wrinckled, but sadly grieving the Old Woman, especially upon the change of Weather." And yet the poor woman could not rid herself of the horns. You can almost imagine the audience leaning in, taking in each of the bookseller's words... "She hath cast her Horns three times already; The first time was but a single Horn, which grew long, but as slender as an Oaten straw: The second was thicker than the former: The two first Mr. Hewson Minister of Shotwick (to whose Wife this Rarity was first discovered) ob|tained of the Old Woman his Parishioner: They kept not an equal distance of time in falling off, some at three, some at four, and another at four Years and a halfs Growth. The third time grew two Horns, both which were beat off by a Fall backward." And if the pennies weren't being loosed from tightly clasped purses, the bookseller might offer one more fantastic detail about what happened to the horns... "One of them an English Lord obtained, and (as is reported) presented it to the French King for the greatest Rarity in Nature, and received with no less Admiration." (Yes, it seems the poor woman's horns may have been given to King Louis XIV of France! Surely, owning a woodcut detailing the story was the next best thing to seeing the horns with one's own eyes?) The early modern townspeople and merchants and fishwives--and anyone else who enjoyed the strange account--might purchase the piece to share with family and neighbors later. After passing it around, and thoroughly re-reading the story, the buyers might even paste the pennypiece somewhere on their walls, a cheap way to decorate their homes. Hmmm....maybe we should go back to pasting strange and wonderful stories on our walls. What do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed