|

Well, we've finally reached the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London (Well, sort of. We're on a different calendar now, but I guess it doesn't really matter really). The dome of St. Paul's is all lit up... ....and London--or at least a replica-- is about to start burning! The Great Fire has served as the main inspiration behind my Lucy Campion mysteries. When I was working as a PIRATE aboard the Golden Hinde in London, I was always so fascinated by the incredible changes wrought by both the plague and the Great Fire. I was even more intrigued by the so-called "Miracle of the Great Fire" too.

My first book, A MURDER AT ROSAMUND'S GATE, ends with London in flames. My second book, FROM THE CHARRED REMAINS, picks up two weeks afterwards, when Londoners are wearily starting the massive clean-up of the City, and the Fire Courts are established. The aftermath of the inferno continues in THE MASQUE OF A MURDERER and A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET. For those who survived the plague and Fire, London was a very different world--frightening on the one hand, but rife with opportunity for commoners and criminals alike....

1 Comment

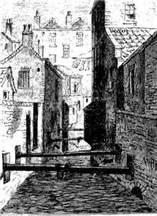

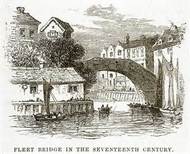

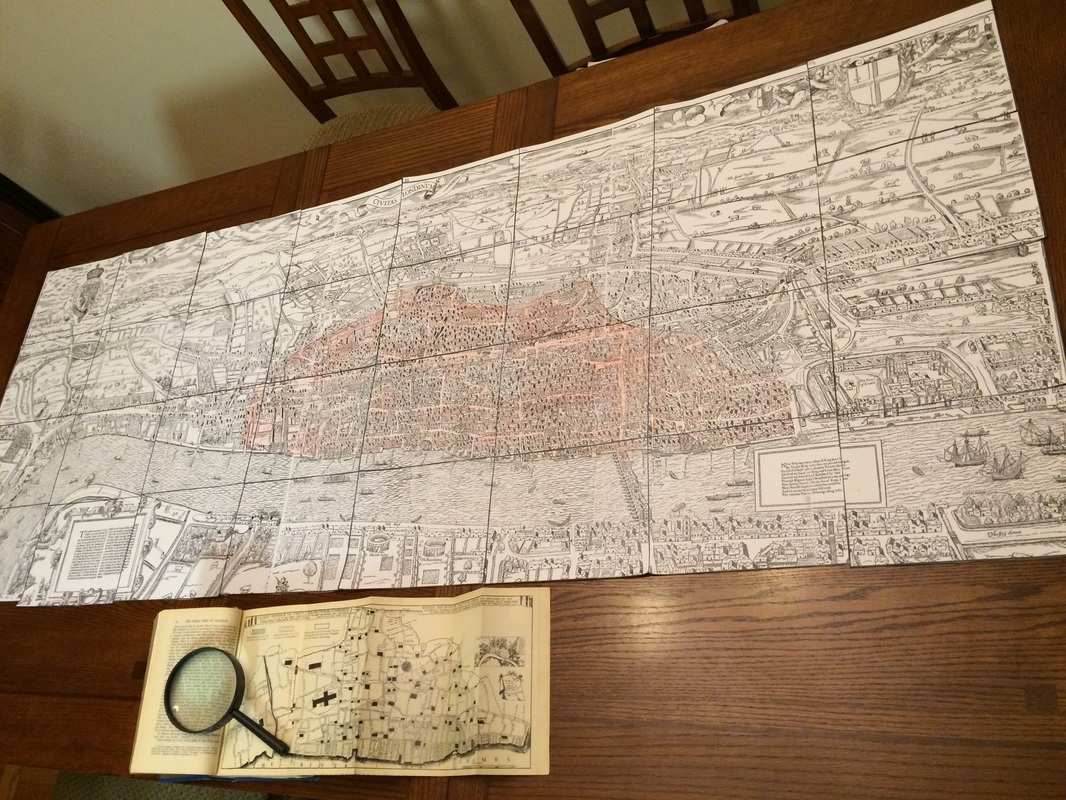

When I first began to conceive of A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET (to be released April 12, 2016!), an image came to me that ultimately informed the entire novel. That image was of a young woman, barefoot and clad only in her shift, stumbling at dawn through the rubble left by the Great Fire of 1666 (and yes, I am counting down to the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire! See counter to the right!) And, of course, I needed her to run into Lucy, so that my intrepid chambermaid-turned-printer's apprentice would have a reason to be involved in the mystery that follows. But it took me a while to figure out exactly where this encounter could reasonably occur. I thought at first the woman could be found on London Bridge. And I really wanted to write something about how the impaled heads of traitors, which lined either side of the Bridge, had caught fire. After all, in Annus Mirabilis Dryden had described in macabre detail how sparks had scorched the heads: "The ghosts of traitors from the Bridge descend, But then when I did a little more digging, I discovered that London Bridge had been damaged in the Fire, and really was not much of a thoroughfare in the months that followed the blaze. Indeed, there would have been no good reason for Lucy to be traveling in that direction, particularly so early in the morning. So I realized that, first, I needed to think through what Lucy was doing out of Master Aubrey's house, just before dawn. Not too hard to figure out actually. She needed to be delivering books. But then the question became, in what direction did she need to travel to deliver those books? Most people were living to the west of where the Fire had stopped. So why would she be going into the wasteland at all? To figure out this challenge, I began to systematically create a large scale map of Lucy's London using photocopies of reconstructed maps of the period. As I marked in red the burnt out area of London, I realized that the Fire line had been stopped to the west along the River Fleet. The River Fleet? This was not a river I knew anything about. A vague recollection that the Romans had used the river to transport goods, but I couldn't remember ever hearing about it otherwise. I became even more curious when I saw that several bridges, including the Fleet Bridge and Holborn Bridge, crossed it. Clearly, the river was wide enough or significant enough to require actual bridges, so it couldn't just be a stream. Intrigued, I began to read more about this mysterious river. From the maps I could see that the river flowed from the north, went through the Smithfield butcher markets, traversed Fleet Street, and emptied into the Thames. There was also a region that surrounded it, awesomely called "Fleet Ditch." [Sidenote: I really wanted my book to be called "Murder at Fleet Ditch," but that title didn't even make it past my editor. A little too stark, I guess.]  By all accounts, by the 17th century, the River Fleet was no longer a river where boats could easily travel, but had instead become a place where people would dump animal parts, excrement, and general household waste. Indeed, Walter George Bill, one of the great original historians of the Great Fire, described the River Fleet as an "uncovered sewer of outrageous filthiness." And yet, there were still accounts of people bathing in its waters (yuck) and even drinking from it (yuck, yuck, double yuck), despite its considerable stench and grossness.  So the River Fleet--and the original bridges that crossed it--formed a natural backdrop for my story. I could not find a picture of the 17th century Holborn Bridge, but I thought this artist's rendering of Fleet Bridge might serve as a model. And because the Holborn Bridge was still in place after the Fire, with the unburnt area and markets on one side, and the burnt out area on the other, it became the perfect place for Lucy to encounter this desperate woman.  My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... But of course, I was still curious...is there still a River Fleet? The answer is, yes, of course, but it was finally bricked over in the 1730s, after being declared a public menace. It was still problematic though, particularly in the 19th century, when a great explosion occurred as a result of the expanding gasses in the pipes below the streets. Raw sewage apparently spilled everywhere!!! (Don't even think I wouldn't use that awesome detail if I ever set a book in 19th century London. But I doubt it would make it to the cover!) And if you want to know more, here is a nice overview of the history of the River Fleet in all its--ahem--glory. I'm always interested in the process of world-building. While world-building is important for any story, I think that it is even more critical when writers are creating an unfamiliar world for their readers. So, for example, my books are set in 17th century England, during the time of the plague and the Great Fire of London (check out my countdown to the right!!!). While many people know about the Tudor England or the Regency period, the 1660s are a far less familiar period. So, I spend a lot of time thinking about larger cultural, social, political and gender trends that helped define my world, as well as norms, conventions and features of the period. But I think world-building is also important for those setting their books in the future, by nature an undefined period. So I invited author H.A. Raynes onto my blog today to talk about how she went about conceiving and building the future for her debut novel, NATION OF ENEMIES.  Nation of Enemies is set in the near future world of 2032 in the United States. People ask me why that year, in particular, and how did I go about creating that future world? First, the choice to set the story in 2032. Integral to the plot is a presidential election, so that was key in determining the year. Next, and importantly, I wanted it to be near enough that we can almost feel it...imagine it. It’s in our lifetime, depending on our age. I didn’t want to get caught up in the technological advances which would put Nation of Enemies more in the sci-fi realm, which would make it a different book entirely. And so then came the research. In this world I built, the United States is war-torn, like any war-torn country, wrecked by attacks, non-functioning in many ways. People have left the cities, which are easy targets, and fled either to the countryside or else attempt to emigrate to safer shores. They’re less concerned with technology and comfort and more concerned about the safety of their families. As the economy fails, government spending goes toward fighting the war and maintaining hospitals that are on the front line. A doctor is one of my protagonists and for his point of view, I researched the future of medicine. Genetics, equipment, medicine. How a hospital might function with advances in these areas. I interviewed a friend who is a doctor and used the internet at length. Of course, there’s reality and predictions of what will be in the future. I combined those elements with my imagination. I also combined them with the politics of war when I introduced the legislation of the MedID biochip citizens are forced to wear in 2032. There is an actual biochip in use today, though it is quite simple in comparison to my MedID and how it’s been manipulated by the U.S. government. There’s freedom in creating a future world. I also considered schools - what would happen if schools became even more of a target than they are today? (Though just this week, several schools in my state of Massachusetts had bomb threats.) Knowing that parents are vulnerable, I imagined terrorists using schools to, well, terrorize society on a whole new, emotional level. That forced me to bring all schools online in 2032. Kids attend class virtually, creating a safer but less social educational experience. But children suffer in this way, locked in their bedroom away from friends and situations that foster personal growth. Finally, I researched the future of the internet, the language used by experts in the field, and the hackers who exist in a darker but very real realm. It was both fascinating and frightening to discover the skills of these hackers and how they challenge governments and corporations on a daily basis for their own agendas. To “futurize” my novel, though I used terminology hackers currently use along with society’s (and government’s) fears about their power, I simply ushered them down the path. As firewalls and encryptions become more sophisticated, so do hackers. Already we are experiencing hacks into financial institutions and government agencies - I found it easy to imagine an even more widespread problem, especially when the country is distracted by war. I don’t want to spoil any plot points in Nation of Enemies, but recently there was an aspect of the Paris Attacks that included an element I used (researched and pushed farther) in terrorist communications. It sent a chill up my spine. My near-future world of 2032 is not one in which I want to live. I’m a hopeful, positive person and I have great hopes for the futures of my children. Sadly, it wasn’t difficult and in fact was quite plausible to imagine the darker side of humanity emerging with the state of the world we live in today. Let’s hope my imagination does not win out. Doesn't this book sound great?! Here's the official blurb: 2032. Turned away by London Immigration because of his family’s inferior DNA, Dr. Cole Fitzgerald returns to work at Boston’s Mass General hospital. He purchases ballistics skins for family, a bulletproof car and a house in a Safe District. As the War at Home escalates, Cole begins an underground revolution to restore civil liberties and wipe away the inequity of biology. Along the way he’ll risk his family, his career and his life when he discovers the U.S. government may pose a greater threat than the terrorists themselves.  H.A. Raynes was inspired to write NATION OF ENEMIES by a family member who was a Titanic survivor and another who escaped Poland in World War II. Combining lessons from the past with a healthy fear of the modern landscape, this novel was born. A longtime member of Boston’s writing community, she was a finalist in the Massachusetts Screenwriting Competition and has published a short story in the online magazine REDIVIDER. H.A. Raynes has a history of trying anything once (acting, diving out of a plane, white water rafting, and parenting). Writing and raising children seem to have stuck.  I've been waiting for 2016 for a while. Since the Great Fire of London serves as the backdrop for my Lucy Campion mysteries, I decided I wanted to personally commemorate the 350th anniversary of the event here on my blog. And what better way than a countdown?! Check out my nifty calendar to the right! What is interesting, of course, is that the Fire was commonly understood to have begun on September 2, 1666 around 2 am.  Yet, as I have pointed out elsewhere, that was according to the Julian calendar. In France, where they used the same Gregorian calendar that we use today, the tragedy actually occurred on September 12, 1666. So confusing!  I'll talk about some of the other aspects of the Fire in future posts, (including 1666 as the "Devil's Year") but I thought for now, I'd offer the first-hand description from diarist Samuel Pepys. Personally I'm always struck by the calm way he describes the events, particularly in the first passage: "Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today, Jane called up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose, and slipped on my night-gown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back side of Mark Lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off, and so went to bed again, and to sleep. . . . By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down tonight by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish Street, by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently, and walked to the Tower; and there got up upon one of the high places, . . .and there I did see the houses at the end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side . . . of the bridge. . . . So down [I went], with my heart full of trouble, to the Lieutenant of the Tower, who tells me that it began this morning in the King's baker's house in Pudding Lane, and that it hath burned St. Magnus's Church and most part of Fish Street already. So I rode down to the waterside, . . . and there saw a lamentable fire. . . . Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that lay off; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies, till they some of them burned their wings and fell down. Having stayed, and in an hour's time seen the fire rage every way, and nobody to my sight endeavouring to quench it, . . . I [went next] to Whitehall (with a gentleman with me, who desired to go off from the Tower to see the fire in my boat); and there up to the King's closet in the Chapel, where people came about me, and I did give them an account [that]dismayed them all, and the word was carried into the King. so I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of York what I saw; and that unless His Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him, and command him to spare no houses. . . [I hurried] to [St.] Paul's; and there walked along Watling Street, as well as I could, every creature coming away laden with goods to save and, here and there, sick people carried away in beds. Extraordinary goods carried in carts and on backs. At last [I] met my Lord Mayor in Cannon Street, like a man spent, with a [handkerchief] about his neck. To the King's message he cried, like a fainting woman, 'Lord, what can I do? I am spent: people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.' . . . So he left me, and I him, and walked home; seeing people all distracted, and no manner of means used to quench the fire. The houses, too, so very thick thereabouts, and full of matter for burning, as pitch and tar, in Thames Street; and warehouses of oil and wines and brandy and other things.  A little belatedly I am taking part in the September Sisters in Crime Sinc-Up for writers. (There are a few days left of September, right?) So one of the prompts was this question, "If someone said 'Nothing against women writers, but all of my favorite crime fiction authors happen to be men,' how would you respond?" Well, someone did say something along these lines to me once... I was at a mystery conference, and a fellow author introduced me to an older gentleman--I'll call him George--who apparently is a huge history buff. My friend told George that I write historical mysteries set in seventeenth-century London. George's eyes lit up and he told me that he had just been in London recently. I asked him what he had liked about his trip. George told me that he had liked seeing the Cheshire Cheese, a tavern that had been rebuilt in 1667 after the original was burnt down during the Great Fire of London. We-l-l-l-l....the Cheshire Cheese was actually the setting of my second novel--From the Charred Remains. In fact, I have a murder happen there just before the place burns down. So I told George this, and again, his eyes lit up. Then he asked me about my protagonist. I started to tell him about Lucy, my chambermaid-turned-apprentice, and he held up his hand and said, "I don't read books about women." Conversation over. Wha-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-t? I couldn't even begin to tell him about all the wonderful crime fiction that feature female detectives, sleuths, lawyers, reporters and a zillion other investigators that he was missing out on with such a dismissive stance. Patricia Cornwell's forensics specialist Kay Scarpetta. Rhys Bowen's amateur sleuth Molly Murphy. Kerry Greenwood's private investigator Phryne Fisher. Sara Parestsky's kick-ass V.I.Warshawski. Hank Phillippi Ryan's intrepid TV reporter Charlotte McNally. Not to mention the unflappable Miss Marple! And for anyone who likes strong female protagonists in historical mysteries, I've got a few that you MUST check out: Meg Mims writes the "Double Series" featuring feisty Western heroine Lily Granville; Anna Loan-Wilsey writes a terrific series set in New England featuring Hattie Davish, "a travelling secretary and dillettante detective," and Alyssa Maxwell writes the charming Gilded Newport Series with Emmaline Cross--"a Vanderbilt by heritage, a Newporter by birth, and a force to be reckoned with!" Well-written historical mysteries all! Hopefully we can turn the Georges of the world around, one fabulous female protagonist at a time! What about you? Who are your favorite female sleuths, detectives and investigators? Why do you enjoy them?

what bad event might have happened here? what bad event might have happened here? Since my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate, was published in 2013, I have gotten many questions about my writing process. “Are you a plotter or a pantser?” is the question I most often get. Back then, I didn’t even know what the question meant. Now I know the questioner wants to know whether I outline my books in elaborate detail before I start writing (plotting), or do I go by the seat of my pants (pantsing), figuring out the plot and details as I go. I want to say that I’m usually captivated by an opening image—and that’s what my story revolves around. For my first novel, I have a young woman walking innocently up to a man she knows, who then surprises her by sticking a knife in her gut. Who was this woman? Why did she trust this man? And of course, why did he kill her? (Ironically, the image that inspired A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate never even made it into the final version. I had written it as a prologue, but I worried about starting the story twice. You can check it out here, if you are interested.). However, I've now learned that some things truly need to be figured out before I start writing the book. As I start my fourth Lucy Campion novel, I thought I'd try to share something of my process of thinking through the plot. I have my opening image, and--for now--a one paragraph description of the plot: When the niece of one of Master Hargrave’s high-ranking friends is found on London Bridge, huddled near a pool of blood, traumatized and unable to speak, Lucy Campion, printer’s apprentice, is enlisted to serve temporarily as the young woman’s companion. As she recovers over the month of April 1667, the woman begins—with Lucy’s help—to reconstruct a terrible event that occurred on the bridge. When the woman is attacked while in her care, Lucy becomes unwillingly privy to a plot with far-reaching political implications. So I have my opening image, but now I have to start thinking through all the big questions. Initially, I seem to do this as a reader. Who is this woman? What happened to her? What was this terrible event? Was it something that she witnessed, or is she physically injured. Whose blood is it? Why is she on London Bridge alone?

Then I will start the hard part--thinking through these questions as a writer. I've definitely learned that I need to figure out who the antagonist is from the outset. My natural tendency is to reveal the story to myself (pantsing), probably because I'm naturally more interested in how terrible events affect a community, not why people do terrible things. However, that approach usually means I don't know whodunnit, and that's a challenge for a mystery writer! I usually have to do a lot of backtracking and rethinking motivations and actions, when I have not worked out who the killer is upfront. So then, my next set of questions will be plot-related. What is this terrible event that occurred? Why did it happen? Who caused it to happen? How did this young noblewoman get involved in such a thing? And--sadly enough--I need to figure out if the London Bridge will work as a backdrop. I know it got burnt in the Great Fire, but I'm not sure yet how feasible it is that she ends up there. Then, because Lucy needs to be brought in, I need to figure out what makes this so urgent. Will this woman be attacked under Lucy's care? Probably. Why? What does she know? What are the larger implications of this crime. So, over the next week or so, I will brainstorm these big questions, and from there--voila!--a plot of sorts will emerge for me. I will figure out anchor points, motivations, and subplots from there. Then I will start writing. Every time I hit a roadblock, I will just start the questioning process again, until I figure out the direction I need to take to move forward. So I will call my approach, Plot-Pantsing. What about you? If you are a writer, what approach do you prefer? As a reader, do you think you can tell which approach a writer took?  the codes in the fire poems... There's been sort of a funny game of tag going among writers recently, called "The Next Big Thing." So crime fiction writer Holly West was kind enough to tag me, which means it's my turn to answer some writerly questions and tag some other writers. 1) What is the working title of your next book? After A Murder at Rosamund's Gate releases April 23, 2013 (sigh, yes, I'm still awaiting this great moment), my next book featuring Lucy Campion is From the Charred Remains. That's still my working title at the moment, although I will probably change it when the book gets closer to publication (in 2014). 2) Where did the idea come from? FTCR continues two weeks after A Murder at Rosamund's Gate leaves off; that is, directly after the Great Fire of London in 1666. So many people, including Lucy, were pressed into service to assist in the great clean-up after the Fire. I thought for sure secrets would have to emerge from charred remains. Of course, plucky Lucy has to be the one to encounter an intriguing puzzle.... 3) What genre does your book fall under? FTCR is a mystery, and within that historical fiction and traditional. I'm not quite sure if readers at Danna's awesome cozy mystery blog would call it a cozy or not, but like Anne Perry's books, it has elements of a cozy.  4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition? I don't want to give away my thinking completely (since I prefer readers to imagine characters for themselves) but I wouldn't be adverse to the compelling Michael Kitchen (Foyle's War) portraying my kindly magistrate. 5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book? Ack! The dreaded one-sentence synopsis. Torture to the writer! Here goes... Lucy Campion, a chambermaid turned printer's apprentice, discovers in the aftermath of the Great Fire the body of a murdered man; on his corpse, she finds a poem which she publishes, little realizing that this act would bring her once again into direct confrontation with a murderer. 6) Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency? I am represented by the amazing David Hale Smith of Inkwell Management. Both books will be released by Minotaur Books (St. Martin's Press). 7) How long did it take you to write the first draft? Given that A Murder at Rosamund's Gate took me about ten years to write (seriously!) I'm amazed to say that I wrote FTCR in just a few months. 8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre? I've been inspired by both Anne Perry and Rhys Bowen. 9) Who or what inspired you to write this book? I've been inspired to write these stories ever since I was a doctoral student of history. My husband and kids inspire me every day to keep pursuing my dream... 10) What else about the book might pique the reader's interest? If you like puzzles and codes, this one is for you... On Dec. 19, please be sure to check out these awesome writer's blogs...

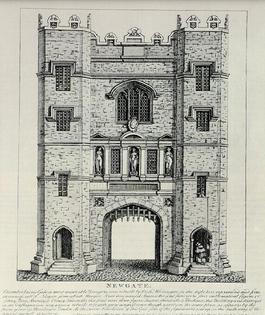

Anna Lee Huber, The Anatomist's Wife Helen Smith, Alison Wonderland  After Newgate burned down, then what? When I wrote the first draft of From the Charred Remains, I focused mainly on getting the story worked out--finding the heart and shape of my tale. I didn't stress too much over language, description, and dialogue on the first go-round--I figured I could elevate my prose later. As for historical details, I frequently had to make my best educated guess about what might have been true in those first weeks after the Great Fire of London (September 1666)...and move on. Now as I work through draft two, I'm doing the hard--I mean fun--part: Fixing and double-checking all the historical details. I've already mentioned two of my recent questions (How plausible was the stated death toll of the Great Fire of London?) and (How far could a horse travel in the seventeenth-century anyway?), but here are a few other things that I've pondered: Since my heroine is now a printer's apprentice (yes, unusually so!) I had to figure out a lot of specifics about the early booksellers and their trade. So I wondered, for example, how did a seventeenth-century printing press operate? As it turns out, the press operated in a remarkably gendered way--parts of the machine were referred to as "female blocks," which had to connect with "male blocks." The interconnected parts were supposed to work together harmoniously, but on occasion--usually when the female "leaked"--the whole press might stop working. (Naturally, the female part was to blame!) And another question: Since three of the largest prisons--Newgate, Fleet, and Bridewell--were all destroyed in the Great Fire, where were criminals held? I had to make my best guess on this one. There were other prisons of course: Gatehouse prison in Westminster, the White Lion prison, the Tower, and my favorite, the Clink in Southwark. But I decided to invent my own makeshift jail--after all, in those chaotic days after the Great Fire, order had to be regained quickly, and it stands to reason that royal and civil authorities might have wanted lawless behavior contained as quickly as possible. I couldn't find evidence to the contrary, so an old chandler's shop became a temporary jail. And were criminals still being hanged at the Tyburn tree immediately after the Fire? Executions resumed quickly after the Fire, conducted as they had been since the twelfth century, in the village of Tyburn (now Marble Arch in London). Prisoners were progressed by cart, from jail to the "hanging" tree, parading through the streets--often praying, preaching, repenting or depending on their personality, even swapping jokes with the spectators. Usually they stopped at a tavern for one last drink along the way, before being forced to do the "Tyburn jig," as Londoners cheerfully called execution by hanging. Of course, I also looked up countless other details...Who used acrostics and anagrams to convey messages? What secrets might be conveyed in a family emblem? And most significantly of all: What happened when the first pineapple arrived in London? Ah-h-h, but I can't tell you about these answers....I'd be giving too much away about Book 2!!! I don't really have a question for you to answer, so I'll just end with a maniacal laugh... MWAH HA HA HA HA....!!!  The backdrop of my second novel, From the Charred Remains, begins where The Murder at Rosamund's Gate left off...at one of the most traumatic moments in London's history: The Great Fire of 1666. Yet as I researched the extent of the devastation, looking at a wide range of sources, I became increasingly perplexed by how few people were alleged to have perished during the conflagration. Over and over, I'd see repeated the same impossibly low numbers--nine, ten, a dozen people. How could that be? You see, the Fire--which started in early September 1666 when a baker failed to bank his coals properly--raged out of control for several days before the winds mercifully shifted. In that time, the Fire destroyed thousands and thousands of homes and businesses, and a hundred thousand people were left homeless. Just imagine--as I've tried to do--the mayhem, the panic, the crush of humanity. Could the elderly, the infirm, the drunk have fled so easily? And what about the inmates of Newgate prison? It's unlikely the wardens of that dreadful place would have thought through a systematic evacuation plan. And yet, historians have long pointed out (very reasonably, I might add) that the death toll could not have been very high. Someone would have noticed. Surely, someone would have written about death on a massive scale. But, such written accounts don't exist. Contemporaries (such as Pepys or other chroniclers from this time period) only noted a handful of deaths. Two elderly women found huddled by St. Paul's. A young serving girl afraid to jump from the third story of a building in flames. Such tales are scattered about, but they are notable in their rarity. More significantly, the Bills of Mortality, which carefully documented all deaths from the plague and other misfortunes in the 1660s, did not describe any great numbers after the Fire. Cover up? hmmmm.... As it turns out, I'm not the only one who has pondered this very question. Neil Hanson, author of The Dreadful Judgment, has made a compelling argument that thousands may have perished in this blaze--in direct opposition to the commonly accepted view. Hanson raised two important questions: Why were these deaths not recorded, and what happened to their bodies? (You can read his fascinating address to the Museum of London here). Sadly, Hanson's conclusion is deeply troubling but may well be accurate--the bodies of the missing had simply disappeared into the flame. Everyone had missing neighbors who never returned....numbering in the thousands. So, this is one of those odd cases where the silence of evidence could be evidence in itself. But what do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed