Understanding Motivation: Why do some writers complete a novel...and others do not? (yet...)10/12/2015 What motivates some writers to complete a novel? This question has been on my mind for a while. Last week, I did a keynote for another university on motivating and engaging students in higher education (a facet of my day job I won’t go into here). After my talk, someone who knew I was also a novelist said to me, “You know, I used to be a really good writer. All through school, from elementary school through college, everyone thought I would be a novelist. But as an adult, every time I’ve tried to sit down and write a novel, I just can’t do it. How did you do it?” Obviously, this person wasn’t asking me how to write a novel—I’m sure she is well aware of the scores of books that explore the craft of novel writing. But she was asking me a more fundamental question about motivation. “I want to write a book. I have the skills to write a book. I even have a great idea. Other people have written books, some far less skilled and imaginative than me. So why can’t I actually complete something I want to do?”  Why indeed? The day after I delivered that keynote on motivation, I traveled to Raleigh where Bouchercon, the world mystery convention, was getting underway. There, I heard variations of the same question being posed over and over to authors everywhere, in panels, in the book room, over drinks in the bar. How did you do it? And underlying that question, the more desperate ones: Why can’t I do this? What do you know that I don’t? To be clear, I am focusing here on the questions posed to novelists about how they complete a book-length manuscript (or do it more than once), not about how they got their books published (a process which generally transcends self-motivation). I began to pay more attention to how authors replied to this question. Setting the flippant replies aside (“Lots of chocolate!” “Wine!”), a lot of them said things like “Find the kind of writing style that works for you and stick to it.” “Write a set amount of words a day!” “Just keep going!” or most succinctly, “Butt. In. Chair.” Everyone has heard this sincerely intended, tried-and-true advice a million times. The questioner would dutifully nod, but the puzzled look would remain. How do I actually do that? I know what I’m supposed to do, but I don’t actually do it. Why can’t I do what you do? [It's like trying to lose 15 pounds. We all know we're supposed to exercise daily, eat vegetables, avoid sugar, and watch our portions. Or whatever. But it's hard to do.] On the flip side, when I was chatting with some of these writers, I’d ask them what they thought was keeping them from finishing their novels. Here, there were a few variations on a set of themes. Sometimes they focused on time. I have a full time job. I’m taking care of my children, aging parent etc. I can’t find a set time every day to write. I don’t have time to do the research. Or sometimes, they focused on the story itself. I don’t know where to begin. I have writer’s block. The middle is completely confusing. I don’t know how to end my story. My critique group has confused me and I don’t know what to do. Sometimes, they focused on doubt or self-worth or other emotions. I’m just not sure if my story is any good. I don’t know if readers will like it. People are expecting something really great from me, but they’ll know I’m a fraud. I’m not really a good writer. All challenges. All difficult and stressful things. All things that can keep a person from completing a novel. But I’m telling you with some confidence: Every writer who has successfully completed a book-length novel has probably experienced all or most of the same constraints, challenges and boulders in the road. But the difference is, they successfully managed to navigate the obstacles. So the question is: How? Or maybe, Why? [And the answer is not, I assure you, that they are somehow better or more talented than everyone else!] Interestingly, motivation theory can do much to explain why some people successfully complete a given task, and others do not. I’ll say right now that I don’t have a magical novel-completion formula on hand. But I do have a set of questions and some thoughts that might help writers explore their own motivations more fully. These questions include:

Go ahead. Think about these questions. Write down a few thoughts. I’ll wait.

3 Comments

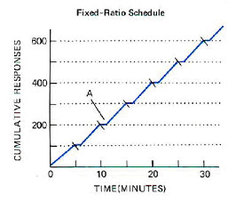

What's he waiting for? What's he waiting for? A few weeks ago, I received my editor's notes for A Death Along the River Fleet. As always, the comments were insightful and thorough, but not particularly hard to address or to think through. And yet I found myself wanting to do anything but sit down and work on them. Everything else was suddenly more immediate, more necessary--organizing a desk drawer, writing a blog post (including this one), and a vast array of other far less important things and activities. Classic procrastination, right?  http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg http://www.betabunny.com/behaviorism/Images/FR.jpg But why? Why would I procrastinate on a task that I knew I wouldn't mind doing--that I might even enjoy doing? I mean, usually when I procrastinate, its because there's a task looming that I really don't want to do. Like, cleaning the litter box. Pulling weeds in the garden. Other tedious or annoying tasks like that. So why was I putting off a task that I didn't really mind doing? If it's not procrastination, is it simple weariness? Or maybe fatigue? But I didn't really feel exhausted. I mentioned this question to my husband--my alpha reader and in-house cognitive psychologist--because he can offer a psychological explanation for anything that plagues me as a writer (e.g. Me: "Why can't I remember what happens in my books?" Him: "You're not crazy, you're just experiencing proactive interference.") So in this case, he told me that my most recent issue was probably not truly procrastination, but rather something called a "Schedule of Reinforcement." So the schedule of reinforcement goes something like this: Imagine that an adorable little rat with a bright twitching nose is in a box with a lever. That rat is on a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, which just means it will receive a food pellet (reward) after every 100 lever presses. Once the rat begins to press the lever, it will work at a fast steady pace until the food reward is earned (the up slope in the figure below). (So if I'm the rat in this scenario, I've earned my reward--I've sent my book in to my editor and received my edits.) However, once the rat earns the reward, it stops responding for a while (the flat point A in the figure). This is known as either the “post-reinforcement pause” or the “pre-ratio pause.” Essentially, the length of the pause is proportional to the amount of work that was required to get to the reward. The interesting part, he explains, is that, generally, the length of the pause is not due to fatigue. Instead, the rat--or other organism, like a human being--seems to use that time to mentally prepare for the large amount of work to come. He says it’s not fatigue because if you artificially get the organism to begin (e.g., place rat paws on lever so that it depresses), then the organism will go on a “ratio run” and perform the behavior until the next reward is given (even if it just completed a run and had no break). So apparently, this has interesting implications for procrastination with humans. As he explains, research on schedules of reinforcement suggest that the best way for a human to overcome procrastination is to artificially get the human to begin the project. For instance, if a college student has to write a term paper, s/he can trick themselves by saying, “I’m only going to write the first two sentences and then I’ll stop.” Often, once they begin, they go on a “ratio run” and write much more than intended (just like when the rat was forced to depress the lever). So, the takeaway for writers (because this is apparently what happened to me): "When you have to dig back into a project (e.g., edits), it’s probably not fatigue that leads to procrastination. That “procrastination time” is used to mentally gear up for the considerable amount of work to come. Even so, simply starting (e.g., on the easy edits), can lead to a ratio run and solid progress." So a scientific explanation for what we all at heart know is the secret for overcoming procrastination: Get your butt in chair and JUST START....but start with the easiest thing possible. The rest will come. And hey, let me know if you have any other writerly conundrums that you would like a professional psychologist to explain. He can come up with a theory for anything. Just address your query to "Dear Alpha Reader." :-) I think it looks beautiful! Great movement--a fresh direction. Who is that woman anyway..? Why is she running...?

All secrets will be revealed April 2016...!!! I received a query from a reader yesterday that gets at the many meddlesome and troublesome questions that writers of British historical fiction inevitably face--How do nobles address each other? "...I just wanted to know: if the oldest daughter of an earl was going to soon be marrying the oldest son of another earl, how would they address one another? The setting is 1860s London, if this helps answer my question. I have read many websites and guide-books that explain how the peerage would be addressed by various people in various situations, but I am having trouble finding information about two people, both children of earls, who are engaged to be married. Would they be more casual with one another? Or would it be inappropriate to address one another without their appropriate title? Your help would be greatly appreciated. Thank you." --Maryam. This is indeed a tricky question. I know something about the forms of address in 17th century England, but I didn't want to assume what was common or expected in the 1660s would be the same 200 years later, in the 1860s. So I threw this question out to the lovely and talented Sleuths in Time, who have spent a lot more time than I have thinking about this question.

So, first, the basics. According to Tessa Arlen: "The eldest daughter of an earl would be called Lady Susan; that would be the extent of her title until she marries. If she were to marry an ordinary man she would be called Lady Susan and then his surname: Lady Susan Blogs for example. The eldest son of an earl might be given an honorary title of his father's of a lower rank this would be given to him until he inherited his father's title. For example, his father who is Roger Parker, Earl of Bainbridge might bestow the honorary title of viscount on his eldest son. So the son's name and title would then be Denis Parker, the Viscount Lord Winslow. It is also important to remember that the Earl of Bainbridge would have a family name, in this case Parker." This seems pretty straightforward so far, right? Tessa continues: "I can't imagine why this young couple would call one anything other than by the first names when they were alone together. And if they are English the usual terms of endearment! If they were together out in society Lady Susan would be referred to as the Vicountess Lady Winslow and her husband would be the Viscount Lord Winslow and they would be announced as Lord and Lady Winslow. When Lord Winslow's father dies and he inherits the earldom he will become the next Earl of Bainbridge - and be called Lord Bainbridge and his wife would become the Countess of Bainbridge. The order of precedence can be very confusing - even for Brits. So tell your friend to follow this pattern and she will sound like she knows what she is talking about!" Excellent advice! Alyssa Maxwell also commented: "Sometimes the son and heir would be called by his courtesy title without Lord in front of it, as in Brideshead or Bridey as friends and family called him in the book." She also directed us to Jo Beverley's Guide to English Titles in the 18th and 19th centuries, a very helpful resource! As Anna Lee Huber further notes: "In the case of an earl, he usually does have a lesser title (viscount or baron) he can grant his eldest son as a courtesy, but it's also possible he doesn't. (Author's choice since it's fiction.) In that case he would be called Mr. Parker by his fiancé in public, Denis in private. The rules for daughters & sons of earls are slightly different. Daughters of dukes, marquesses, & earls receive the honorary Lady before their first name. Only sons of dukes & marquesses receive the honorary Lord before their first name." And to round us out, Ashley Weaver says, "I have always found [Laura Chinet's] site really useful for reference. She has little charts and everything!" [I will say, however, that what Laura Chinet describes for the 18th and 19th century may be different from 17th century conventions. In my research, I have seen many letters between family members that use endearments, like "My dearest Anne." So it stands to reason that if they use such intimacies in written letters, they would do the same in private conversations. There is a formalization of speech and manners that happened in the mid 18th century that was not as pervasive in earlier centuries-SC]. Ultimately, in my opinion, this comes down to an accuracy vs authenticity kind of question. I think writers of historical fiction should try their best to be as reasonably accurate as possible, but ultimately their focus should be on telling the best story possible, without jarring the reader. Hmmm.....what should I be watching? It's a Friday night, and I feel like starting a new mystery or crime-related series on TV, but I think I've run out of options. Can that be true? (Note: I never really watched classics like Perry Mason, Murder She Wrote, or Magnum PI and sometimes I wonder if it's too late to watch them now. What do you think?) I've listed my favorites below: So, what am I missing? All-time Favorites:

Enjoyable Mystery-Themed Shows I would watch again:

Honorable Mentions that May Not Pass the Test of Time (I don't want to re-watch to find out!)

Mysterious Not-Exactly-Mystery Mysteries that I Enjoy:

What about you? Which are your favorite television crime/mystery shows? Is it too late for the classics? Any recommendations for me?  A head-scratcher here... Recently, a friend of mine lamented on Facebook that she had just received another rejection to her agent query--and was clearly getting frustrated--a state to which I could relate. I made some sort of sympathetic comment about hanging in there, that every author experiences rejection, and to keep persevering. Or maybe even start a new project and set that one aside for a while. Platitudes perhaps, but sincerely meant. Well, I was quite surprised when other people jumped all over my comment, saying that rejection should be celebrated and that I was in the wrong for expressing sympathy. That rejection wasn't supposed to be viewed negatively. Now, I do understand about learning from feedback, no matter how negative, but celebrating rejection seems counter-intuitive. Giving yourself permission to take risks, permission to fail--these are things I believe in too. But permission to celebrate rejection and failure, as if these are the expected end products of a writer's journey--that I can never endorse. (Unless of course one wishes to remain unpublished, than by all means, celebrate rejection.) I thought this was an isolated incident, until I read a piece today by author Bryan Hutchinson, who talked about being wary of the rejectionists: "There’s a new bandwagon in the writing community, actually, it’s in nearly every community. The trend dictates that it’s okay to fail, in fact, it’s not just okay – you should expect to fail. And if you’re not careful you might jump on, tricked into not living your passion and not striving to achieve your goals." I could not agree more. Over the last few years I've had the good fortune of being able to spend a lot of time with other published authors--at conferences, at bookstores, or just over a drink--and one thing that still amazes me is how hard every single one of them had to work to get to where they are. I don't know a single author who doesn't have stacks of rejections and years--even decades--of toil, heartbreak, and anguish behind the image they present to the public, no matter how successful they appear now. Striving to get an agent, striving to get a publisher, striving to get the next contract, striving to develop a readership base...its all there. Every author I know says persistence and determination (and yes, maybe a lucky break) are crucial. We may cope with rejection in different ways, but the common element seems to be to grit your teeth and move forward and just...keep...trying. (I'm not saying this has to be done without copious amounts of ice cream, or alcohol, or rejection letter bonfires...) Simply speaking: There are no overnight successes. Just look at Jenny Milcham's fabulous Made it Moments blog and read through the inspirational stories there. No author's "Made it Moment" is the same, but the sense of perseverance is ever present. (Heck, check out Jenny's own story--she's incredible). Bottom line:

Rejection, yes it happens. It's painful, it hurts, its part of a writer's journey. LEARNING FROM REJECTION (or FAILURE)=GOOD THING. But CELEBRATING rejection, as if rejection should be the end in itself?!... NO! That's when dreams die. After my kids go to bed tonight, I'm going to be sinking into a novel that I've been looking forward to reading since I first heard about it-- Lori Rader-Day's, Little Pretty Things. In preparation I invited Lori to join me on my blog today and answer a few questions about her second novel, to be released July 7, 2015 from Seventh Street Books. But first, the official blurb:  OLD RIVALRIES NEVER DIE. BUT SOME RIVALS DO. Juliet Townsend is used to losing. Back in high school, she lost every track team race to her best friend, Madeleine Bell. Ten years later, she’s still running behind, stuck in a dead-end job cleaning rooms at the Mid-Night Inn, a one-star motel that attracts only the cheap or the desperate. But what life won’t provide, Juliet takes. Then one night, Maddy checks in. Well-dressed, flashing a huge diamond ring, and as beautiful as ever, Maddy has it all. By the next morning, though, Juliet is no longer jealous of Maddy—she’s the chief suspect in her murder. To protect herself, Juliet investigates the circumstances of her friend’s death. But what she learns about Maddy’s life might cost Juliet everything she didn’t realize she had. Can you tell us a little about Little Pretty Things? Little Pretty Things features Juliet Townsend, a not-quite-30 woman stuck in her hometown and in a bad job, cleaning rooms at a low-rate roadside motel where only crackpots and cheapskates stay. Then her former best friend and high school track team rival shows up—rich, beautiful, and everything that Juliet isn't—and checks in. What could have been a reunion takes a turn when Juliet discovers her friend's body the next morning. The book is about women's friendships, competition, and growing up, finally, long after you should have. Was it easier, harder or about the same as writing your first novel, The Black Hour? (What I’m really curious about is whether this was a similar process for you, or different?) I started Little Pretty Things back before my first novel was anywhere close to published, so I had a running start, but then I realized how much work publishing and promoting a novel was. The drafting part of Little Pretty Things got hung up a bit while I figured out some things, and then my agent sold the second novel before it was done. So in the end I had to write to a deadline for the first time. It was a little challenging for me, but I did learn some things about my own process and, due to my day-job schedule, when in the year's calendar it's best for me to be drafting and when it's best to be editing. Hoping to put some of that self-knowledge to work on my next book, which I'm writing for release next summer. How does your chambermaid compare to my chambermaid? Well, my chambermaid is in modern times, so she's very free to move around as a woman in society—but she really doesn't. Juliet is much more timid, in the beginning, than Lucy is in her situation. What they have in common is that they both won't stay chambermaids for long. (I was just joking when I asked this question, but thanks for the thoughtful reply!!!-SC) What kind of research did you have to do for this book? Well, I've never been a cleaner of any kind, so I read a book written by someone who had worked on the staff of a hotel. Luckily Juliet Townsend isn't much of a cleaner, either, so I didn't have to know how to do the job well. The other topic I had to learn about for Little Pretty Things was running. I was a runner for about five seconds over ten years ago, but I was never a high school track runner. I wrote the book as well as could, using good guesses, and then asked a friend of mine, a writer as well as a former track team runner, to read the book for gross errors. She said I got it right, and gave me a few additional ideas for opportunities to make things even better. I don't have the research background you do, Susie, so I don't mind stabbing into the dark a bit. It's fiction, after all. But I don't want to be wrong about the details that will take readers out of the story and ruin their enjoyment of reading. (Yes...I totally agree! -SC) Thanks Lori, and best of luck!

It seems like every day I receive a Google Alert, kindly informing me that another site has popped up, allowing my books to be downloaded for free. Not only are these parasitic companies stealing from me and other authors, but to add insult to injury, many users actually post comments on these sites, thanking these bottom-dwellers for the "service" they provide to readers. Sometimes these comments are so heartfelt it makes me wonder if the users don't realize they are committing an actual crime. Is that possible? Taking a step away from my indignant high horse for a moment, I do find it interesting that plagiarism and piracy of books has been around since the invention of the printing press. Initially, imitation in the Renaissance was seen as a compliment, a form of flattery, at least in art. In the world of the cheaply printed piece, necessity and practicality were at the heart of imitation. Printers regularly used the same woodcut again and again--say, of someone being hanged--most likely for ease of use and to evoke a certain image or memory in the audience. But over the next century or two, there seemed to be growing concern with the ability of printers to simply reset a piece and sell it for themselves. On occasion, advertisements to booksellers were created, informing them when a "sham" edition of a book had been created. They would implore the bookseller to consider the nature of property; they also seemed to speak to the bookseller's sense of quality, by reminding them of the inferiority of the sham piece. For example, this next advertisement reminds the bookseller that "The sham edition has several mistakes and blunders, contrary both to sense and grammar." Some of these advertisements even specified that the printer, publishers and dealers would be prosecuted by the Company of Stationers, who as a royal guild had the sole power to oversee the publication of most written work, including almanacks as described in this next advertisement. In particular, I like the last line, which warns against those who would claim not to have known they were doing anything illicit: "This notice is given to prevent all persons from coming into trouble through ignorance." Lastly, I suspect this is where the practice of authors signing their own books came from--the author was attesting to the authenticity of his (or possibly, her) books. I don't know if its particularly heartening to realize that piracy and plagiarism are not a new phenomenon for authors. But it is interesting to think that such acts had long been condemned by the publishing community, even if the problem is still present 200 years later.

In my next post, I will tell you what happened to one of these plagiarists...  I'm thrilled to be joined today by Alison McMahan, author of The Saffron Crocus, a Young Adult novel set in 17th century Venice. From the synopsis: Venice, 1643. Isabella, fifteen, longs to sing in Monteverdi’s Choir, but only boys (and castrati) can do that. Her singing teacher, Margherita, introduces her to a new wonder: opera! Then Isabella finds Margherita murdered. Now people keep trying to kill Margherita’s handsome rogue of a son, Rafaele. Was Margherita killed so someone could steal her saffron business? Or was it a disgruntled lover, as Margherita—unbeknownst to Isabella—was one of Venice’s wealthiest courtesans? Or will Isabella and Rafaele find the answer deep in Margherita's past, buried in the Jewish Ghetto? Isabella has to solve the mystery of the Saffron Crocus before Rafaele hangs for a murder he didn’t commit, though she fears the truth will drive her and the man she loves irrevocably apart.  Sometimes readers ask me why I set my YA historical mystery/romance novel in Venice in 1643. Why 1643? Most novels set in Venice are set during its heyday, from the 1300s to the 1500s. Or they are set in Vivaldi's Venice of the 18th century. Or they are set in the 19th century, mirroring the society Henry James setting in novels like Wings of the Dove. But the 17th century in Venice doesn't get much love. Venice was in decline, in between its period of grandeur and the invasion by the Ottoman Turks and Napoleon. Periods of decline are historically just as interesting as periods of greatness. There is much we can learn from them. I picked 1643 Venice for seven special reasons: 1. THE BLACK DEATH. In 1630 Venice, and the rest of what we now call northern Italy, was hit by the Bubonic Plague. Eighty thousand lives were lost in just seventeen months in Venice laone. On the 9th of November, for example, five hundred and ninety-five died. These enormous fatalities greatly affected the city. Even the Doge, Nicolò Contarini passed away. I wanted my heroine, Isabella, to have lost her parents at the age of five to the plague, and to be fifteen at the time the story begins, so the date of the of the story had to be 1643. 2. THE BIRTH OF OPERA. Yes, I know most teens consider opera to be uncool at best, unmentionable at worst. But I'm an opera fan, so there's a little bit of "write what you know" here, and I was hoping that my own love of opera would communicate itself through the pages. The word "opera" itself is an Italian word – it means "labor" or "work" in Italian. Opera originated in Italy when courtiers decided they preferred the "intermezzi," the light-hearted singing and dancing interludes that broke up heavy Roman plays, to the plays themselves. Opera evolved from these Intermezzi. The first complete opera, "Euridice" by Jacopo Peri was performed in Florence in 1600. 3. MONTEVERDI: If, like me, you are a fan of what the human voice can do in song, then you are a fan of Monteverdi. At the time the story of The Saffron Crocus takes place, Monteverdi was the musical director of the chorus of San Marco's Basilica. Because I admire his music so much, I wanted to give him a small role. My heroine wants to sing for the chorus, but only boys can do that, and she uses various ruses to get what she wants, which pits her against Monteverdi. 4. LOST OPERAS: There is something so romantic about lost works of art. Of course, in the 1600s, opera performances weren't recorded. But the scores were written down. You'd think it would be easy enough to keep a score, and copy it over when you need to. But one of the world's greatest operas, L'Arianna, is a lost opera. All we have is one recitative from it, "Arianna's lament," which plays a key role in my story. 5. CASTRATI: Castrati were male singers who were castrated before puberty to keep their voice artificially high. In other words, the baroque world was so opposed to women singing that they preferred to castrate little boys (only a lucky few survived the procedure) rather than let women perform. I was fascinated both by castrati themselves – what were their lives like? And enraged by the idea that Venetian society would prefer to go that far rather than let women sing. A key character in the story is a castrati. 6. CONCERTO DELLE DONNE (consort of ladies). Women could sing in private homes. This practice started after Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara, who established the first group of "amateur" singers to perform for him. They were considered "amateur" because they were women and could not perform professionally (that is, for pay), but in fact they were renowned for their technical and artistic virtuosity. I know professional musicians today who have tried to re-create some of their music and couldn't do it. My heroine sings in salons before she finds a way to sing professionally. 7. THE JEWISH GHETTO: The Jewish Ghetto in Venice was not the first, but it is where we get the name. The English term "ghetto" is an Italian loanword, which actually comes from the Venetian word "ghèto", slag, and was used in this sense in a reference to a foundry where slag was stored located on the same island as the area of Jewish confinement. I have always been fascinated by how the Jews lived in Venice, and almost half of the book takes place there. I could go on and on about what was special about Venice in 1643, as Venice is endlessly fascinating, but I'll stop there. Read the book, or better yet, listen to some of this music, preferably in Venice itself! Alison McMahan chased footage for her documentaries through jungles in Honduras and Cambodia, favelas in Brazil and racetracks in the U.S. She brings the same sense of adventure to her award-winning books of historical mystery and romantic adventure for teens and adults. Her latest publication is The Saffron Crocus, a historical mystery for young. Murder, Mystery & Music in 17th Century Venice. She loves hearing from readers. Feel free to check out her website, visit her on instagram, pinterest, tumblr, or on Facebook, or just send her a tweet! Her books can be found at Black Opal Books, AMAZON US; AMAZON UK.

I'm so happy and honored to say that my third historical novel, The Masque of a Murderer, officially launches today, April 14! And while I may not be quite as giddy when my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate (2013) launched two years ago--because nothing can ever compare to the release of a first novel--I'm still as loopy as I was last year, when From the Charred Remains (2014) entered the world. Recently, in preparation for the launch, I've been answering a lot of fun and interesting questions about The Masque of a Murderer (the historical background, the story and characters, and my writing process etc). So, I thought I'd do a quick round-up here! I welcome you to:

Thanks so much for sharing this journey with me!!! And I appreciate all the bloggers and reviewers who hosted me, including those through Amy Bruno's Historical Fiction Virtual Blog Tours! And I'm always so grateful to the wonderful people at Minotaur, especially Kelley Ragland and Elizabeth Lacks, and my agent David Hale Smith, and of course my wonderful alpha reader, Matt Kelley!! (and now, I turn my attention back to A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, due out April 2016!!!!) |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed