|

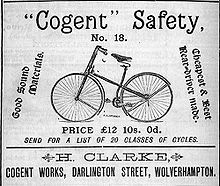

Writers are frequently enjoined to "write what they know," and my guest blogger today has certainly taken that message to heart. Edith Maxwell, author of the the forthcoming historical mystery, Delivering the Truth, features a Quaker midwife in 19th century New England. Edith is a Quaker, has taught childbirth classes, and lives in New England. So I guess she knows what she's talking about!!!  From the official blurb: For Quaker midwife Rose Carroll, life in Amesbury, Massachusetts, provides equal measures of joy and tribulation. She attends to the needs of mothers and newborns even as she mourns the recent death of her sister. Likewise, Rose enjoys the giddy feelings that come from being courted by a handsome doctor, but a suspicious fire and two murders leave her fearing for the well-being of her loved ones. Driven by her desire for safety and justice, Rose Carroll begins asking questions related to the crimes. Consulting with her friends and neighbors―including the famous Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier―Rose draws on her strengths as a counselor and problem solver in trying to bring the perpetrators to light.  Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used Bicycle of the sort Rose Carroll might have used In my Quaker Midwife Mysteries, Rose Carroll is a midwife helping pregnant women give birth in the safest way possible - in the 1888 New England mill town of Amesbury. She’s twenty-four, as yet unmarried, and a Quaker. Rose is an independent businesswoman, unconventional both for going about her business on her bicycle and for being a member of the Society of Friends. Quakers have long been known for being unconventional, though, and New England Friends of the era even more so. Rose’s mother works tirelessly for women’s suffrage. Rose’s friend and mentor, the real John Greenleaf Whittier, was an outspoken abolitionist and supported equality among his fellow humans. Rose addresses everyone by their first name regardless of social class or occupation, and speaks using “thee” and “thy” as Quakers did, so she’s used to traveling outside certain norms. She’s also known for her honesty and clean living. Her clients trust her. Although there was a New England Female Medical College, which was a training school for midwives, Rose took the traditional route and apprenticed with Orpha Perkins to learn her trade. When the elderly Orpha retires, Rose takes over her business. The late 1880s is a fascinating period to write about because so much was changing, including the practice of midwifery and medicine. The germ theory of infection was known, so Rose is careful to wash her hands and keep the birthing chamber clean. A new hospital had been built across the river in the bustling seaport town of Newburyport only a few years earlier. Cesarean sections were done, but it was still a very risky procedure. And male doctors were starting to do deliveries, practicing obstetrics. I read that this practice increased in part because women working in factories were living away from their female relatives who would normally support them through the birth and postpartum period. The husband of one of Rose’s clients insists that his baby be delivered by a male doctor, but most of Rose’s pregnant clients much prefer having a woman attend them. I also read an account of a Massachusetts midwife being sued in 1905 for practicing medicine without a license. I haven’t heard of such accusations twenty years earlier, however. Of course, being a midwife makes Rose a perfect protagonist. She can go places no male police officer can – women’s bed chambers – and hears secrets the detective isn’t privy to, both during labor and at client visits. I know in earlier times midwives had a obligation to extract information from unwed mothers about the father of the baby and report him to the authorities, but I haven’t been able to unearth whether that practice still stood at the end of the nineteenth century. (See Sam Thomas' excellent post on the role of midwives in 17th century England, for example. -SC)  Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission Meetinghouse interior. Photo by Edward Gerrish Mair, used with permission I’m delighted to follow Rose around the streets of my town where many of the buildings of the late 1880s still stand, including the Friends Meetinghouse where she and Whittier worship, and write down her adventures.  Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries (Midnight Ink) and the Local Foods Mysteries, the Country Store Mysteries (as Maddie Day), and the Lauren Rousseau Mysteries (as Tace Baker), as well as award-winning short crime fiction. Her short story, “A Questionable Death,” is nominated for a 2016 Agatha Award for Best Short Story. The tale features the 1888 setting and characters from her Quaker Midwife Mysteries series, which debuts with Delivering the Truth on April 8, 2016. Maxwell is Vice-President of Sisters in Crime New England and Clerk of Amesbury Friends Meeting. She lives north of Boston with her beau and three cats, and blogs with the other Wicked Cozy Authors. You can find her on Facebook, @edithmaxwell, on Pinterest, and at her web site, edithmaxwell.com. Want to know more about the original Quakers from 17th century England? Check out my discussion of the political activities and writing of Quaker women. Or this post on their last dying speeches.

0 Comments

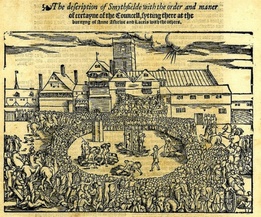

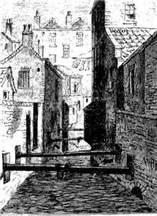

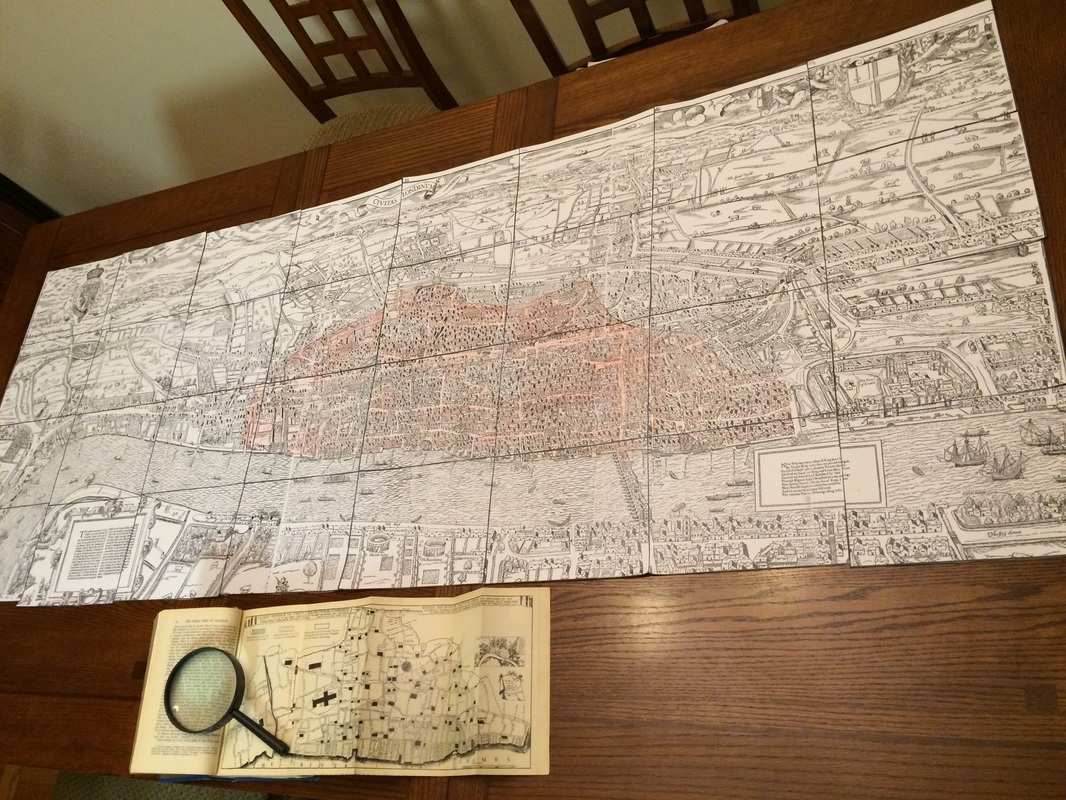

I am delighted to be joined on my blog today by Bridgette R Alexander, author of SOUTHERN GOTHIC: A Celine Caldwell Mystery (to be released March 15, 2016). I had the pleasure of reading Bridgette's debut novel a few weeks ago, and I was struck by the authenticity of her main character's voice. I thought that her amateur sleuth, Celine Caldwell, came across as a "real" teenager--which is actually not an easy feat. So I asked Bridgette to talk about her experience with writing YA fiction. SC: Bridgette, why did you decide to write YA? BA: I grew up loving ABC’s after school specials. What I liked about them was that each story was told from the perspective of a teenage girl, usually, and it gave me a sense that I wasn’t alone in my day-to-day struggles as an adolescent. By that I mean, adolescence is a tough place to be in and you’re there for a long period of time. You are caught between two worlds, one world of a child – its only two or three years ago you were taken to the junior’s section of a department store and your mother was selecting clothes for you. Your world was pretty much being established by the adults around you. Then, there is this other world of [looming] adulthood. Total and complete agency – by you; at 14 or 16 you can make some decisions for yourself, at least what you’re going to wear and who your friends are; and the biggest of all – eros – your attraction and your identity. For me, those moments were paramount. So much so, that I like to view being an adult as an old-kid with benefits. SC: Are there any authors who particularly inspired you? BA: I was introduced to some of my all-time favorite authors when I was in the 7th grade: Mark Twain; John Steinbeck; James Baldwin; William Faulkner; Tennessee Williams; and Hermann Melville. I loved how those works transformed me into the worlds the authors created and caused me to think about the world I inhabited. Then on my own I found the works of other authors and also fell in love with them: Jackie Collins; Harold Robbins; Judith Krantz; I know, I know…they are not exactly children’s authors, but I so loved their works. Mystery and thriller writers I just adore – Agatha Christie, Steven King Joyce Carol Oates and Sarah Paretsky; and of YA writers I really love the work of Sarah Dessen, I love her stories. She totally captures the voice of a strong, independent teenage girl. There are sooo many writers I love, these are just a few of them. SC: What do you enjoy most about writing YA? BA: I like seeing the world fresh again. SC: What kinds of challenges have you faced in writing YA? BA: In writing…not so much. At the moment when I could visualize Celine Caldwell and her life, then her all of her friends and their lives, it was like a motion picture – fluid, moving, colorful and rich with characters. For me it’s been more of a head-game I've had to overcome. The notion of the solitary artist…alone in his or her misery as the only path to creativity is a romantic construct. One that at the on-start of developing and trying to write the Celine Caldwell Mysteries, I thought I was bound to adapt. It was difficult. As a scholar my life was writing among other scholars; sharing my works and dissecting that work with other scholars. As a scholar and thinker I led a fully engaged life. Only in the archives and the library stacks would I actually be in solitude. When I adapted to my writing the engaged-life I was used to, it felt real and true. I am creating characters, developing scenes, structuring the chapters, going back and forth with my editors. SC: How do you make sure your characters are “authentic”? In terms of voice, dialogue, mannerisms? BA: At the beginning of writing Celine Caldwell Mystery series, I organized a teen council made up of girls between the ages of 12 and 18. We’d meet and I’d give them a Celine-Scenario and ask them what would they do or if Celine’s actions were authentic for a teenager, and not just as a teen being driven by an adult. It was important for me to remove myself as much as possible from the equation of Celine Caldwell, 16 year old art world sleuth. Now that’s more of the technical work I’ve done, compared to the easy going fun time I make time for in talking and listening to teen voices. I continue to spend a good deal of time with teenagers because I strongly believe from where I stand it easy for me to “slip” back into the voice and mannerism of an adult person. SC: I know you have a daughter...did you learn anything from her that helped you write your book, or offer insight into the teenager experience? BA: My daughter is the inspiration behind Celine Caldwell. I created [Celine] when my daughter was a newborn. I’d often imagine her future -- how would she relate to the world; what would she look like once she becomes a teenager. My daughter’s life is very different from my upbringing. Her life looks more like the character Celine Caldwell’s with the big exception, my daughter has a doting mother and father. SC: What advice if any would you offer someone interested in writing YA? People or writers hear this a lot…but it stands to be repeated. Write what you know and do it from your soul.  Bridgette R. Alexander is a modern art historian. She received her graduate training in 19th century French art history at the University of Chicago. Alexander worked with some of the world’s greatest museums in New York, Paris, Berlin and Chicago and developed art education programs; curated exhibits; she has taught and published in art history. She’s been featured in a number of publications including, Art + Auction Magazine; the Wall Street Journal; and the Washington Post. SOUTHERN GOTHIC is her debut novel. Alexander currently lives in Chicago and when not writing, she takes her husband, daughter and friends on midnight tours of the cultural institutions. Visit her website (http://celinecaldwell.com).  Civitas Londinum, 1561 Civitas Londinum, 1561 Like the lost River Fleet, another location in London that has long intrigued me is the infamous Smithfield market; a site of enormous contrasts: executions and extreme devotions, torture and merry-making. In the Middle Ages, Smithfield--"a smooth field" to the north of London's walls--was a natural place for jousts, tournaments, and the selling and butchering of livestock. Conveniently (!), animal waste from the market could be dumped into the River Fleet, which flowed into the Thames. It’s original origins as a place where livestock could be bought and sold, can be seen in the vestiges of its street names (e.g. Cow lane, Cock lane).  Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Not surprisingly, Smithfield, like most great open communal spaces was used for greatly varied purposes, including: Public torture: Over the centuries, many criminals—particularly those accused of treason—were tortured. One of the most famous was William Wallace (“Braveheart”)- - a twelfth century hero of the Scottish people. Drawing and quartered was the preferred method, and perhaps castrated as well (but studio executives probably thought movie audiences couldn’t stomach Mel Gibson undergoing that particular humiliation.)  Public executions: While Smithfield was a regular site of hangings and burnings for centuries, under Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary” to her detractors), quite a few Protestant dissenters were publicly burned as heretics. [Interesting side note: According to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, the “Marian Martyrs” would ask that their hands not be bound and their wood pile would consist of the greenest wood, so that their plaintive laments and prayers would last longer.) The burnings of these men and women were collectively referred to as “The Smithfield Fires.” Merry-making and Fair-going: Every August until the mid-seventeenth century, St. Bartholomew’s fair would be held at Smithfield. Originally it was supposed to be only three days of merry-making, but by the 17th century the fair was lasting over two weeks. Check out this advertisement for the entertainment to be had at the “Plow Music Booth” in 16xx:  Anon (1679) Anon (1679) “At the Plow-Music Booth in Smith Field Rounds, (a Red flag being on the Top) during the Time of Bartholomew-Fair, you may be entertained with excellent sports, [such as] Antique dances, entries, cerebrands and jigs, a little girl about 6 years old who danceth with two naked rapiers at her throat, to the admiration of all that ever see her…. With good Wine, Cider, Mum and Mead, and good music for the accommodation of those who are inclined to mirth.”  Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Altham, M. (1691) An auction of whores. Wing / 2858:01 Or of course, for "all single men and bachelors," there was also an ongoing "auction of whores," which--as Michael Altham (1691) joked--contained, “a curious collection of painted whores, cracks, night-walkers, newgate-nappers, bridewell-workers, ladies of pleasue, cart-dancers; with other such dissembling pick-pocket cheats, some pox’d, some clap’d, and some quite rotten and ready to fall in pieces.” Underlying this bill, however a real fear of disease and pollution that seemed to occur whenever so many people were brought in such close proximity. King Charles I tried to cease the Fair on several occasions during his reign. In 1637, he issued a proclamation for putting off the Bartholomew Fair, and a similar fair in Southwark:  Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 Printed by Robert Barker, 1637 “Whereas his Majesty hath taken special care and given several directions, that the usual assemblies and concourse of people might be omitted and forborne, the better to prevent the danger and increase of the infection: Yet finding that the plague is dispersed in sundry places in and near the City of London, his majesty in pursuance of those direction and out of his continual care of the safety of his subjects in general, and of the said city in particular, and to cut off all occasions that may conduce to the further spreading of the sickness, doth hereby declare his royal will and pleasure for the putting off this next fair…” This was only a temporary halt to such festivities; only Cromwell was able to completely stop the fun. The Fair, like all other such festivals, was banned under his regime, only to be restored in 1666 with the Restoration of the fun-loving Charles II.  Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Smithfield Market today (credit: Greg Light) Today, there is little indication of the mass executions and torture that occurred here, although Smithfield Market—now called the Central London Market—is the largest of its kind in London, and one of the largest in all of the European Union. But like the River Fleet, the Smithfield grounds are another part of secret London. There is a long tradition of authors using pseudonyms or writing under Anonymous, and I'm always curious about what makes someone wish to write under someone else's name. I asked Sharon Pisacreta to join me on my blog today, to discuss why she uses pseudonyms (FOUR!) and how she chose them. Her first book in a new series, DYING FOR STRAWBERRIES, will be released November 1, 2016.  Along with spies and people in the witness protection program, authors often feel compelled to change identities. My upcoming mystery series will be released under ‘Sharon Farrow’. It will be the fourth name I’ve used as an author. When my stories and articles first began to appear in magazines, I proudly used the name I was born with. Although it was a tricky Italian name that few non-Italians could pronounce, it made my family happy. However I learned that Shakespeare’s question “What’s in a name?” has special meaning for authors. After I sold my first novel, I thought I’d make things easier for my readers and decided on ‘Sharon Kirk’ as a pseudonym (yes, I’m a Trekkie). Unfortunately, someone in production forgot to read my contract and released that first book under my Italian name. Two other books followed, accompanied by numerous calls from my publisher asking how to pronounce ‘Pisacreta’. Sales reps ran into problems with my name when speaking with distributors. One of my novels was sold as part of a six-book package on the Home Shopping Network, eliciting more questions on exactly how the TV host should say my name. My editor finally asked if I would mind taking a pseudonym. I was happy to oblige. This time I went with ‘Cynthia Kirk’. It sounded British, elegant, and impossible to mispronounce. Soon after, I put aside novel writing and returned to magazine work under my maiden name. I got back in the novel writing game when a friend and fellow author convinced me to team up with her on a mystery series. Because our previous novels were in the romance and western genres, we needed a pen name for our historical mystery series. Marketing is everything in publishing, and an author’s name is a form of branding. If readers want to buy your mystery novel, they don’t want to be confused if you also write science fiction under the same name. We wanted an easy name to spell and remember. The result was D.E. Ireland. Since our series is based on Shaw’s Pygmalion and stars Eliza Doolittle, we chose her initials, transposing them for our first name. Ireland was selected because George Bernard Shaw was born and raised in Dublin. As a writing team, a pen name seemed necessary. Few teams publish under one of the pair’s real name. A notable exception is the Ian Rutledge mystery series by Charles Todd, written by Charles and his mother Caroline. Normally, a new pseudonym is created for the duo, such as Alice Alfonsi and husband Marc Cerasino who write as ‘Cleo Coyle’. All writers should keep a few pen names in their back pocket. If you’re prolific, publishers don’t want to flood the market with too any books under one name in the same year. Because Dean Koontz sometimes published eight books a year, he wrote under eleven different names. Famous authors may feel constrained by their success and want to try something new under a pseudonym. J.K. Rowling writes mystery novels as Robert Galbraith, Stephen King’s alter ego is Richard Bachman. When Anne Rice switched from vampires to erotica, she did so under two pen names. And prolific romance author Nora Roberts chose to write as J.D. Robb for her futuristic mysteries. Because mysteries are so popular, many authors meet demand by writing more than one series under different names. Vicki Delaney writes cozies and suspense novels under both the pseudonym Eva Gates and her own name. Eva K. Sandstrom uses the pseudonym JoAnna Carl for her long running Chocoholic series. Some authors simply prefer using a pseudonym. Janet Quin-Harkin became Rhys Bowen. Juliet Marion Hulme writes as Anne Perry. As we did with D.E. Ireland, choosing a gender neutral pen name also helps attract male readers not prone to buying novels by women. Famous examples include Marion McChesney Gibbons writing as M.C. Beaton, and Edith Mary Pargeter as Ellis Peters. A publisher might also insist on a pseudonym if books written under a previous name had lackluster sales. They often feel it is best to start fresh with a new writing identity. Whether it’s due to a difficult name to pronounce, being too prolific, a poor sales record, switching genres, a writing collaboration, or a desire to conceal your gender, taking on a pseudonym is always an adventure. Finally, writing under a pen name provides a measure of anonymity – and a bit of welcome distance. A bad review directed at books written under your real name cuts a little sharper than one aimed at one written under a pseudonym. It may sound odd, but it’s true. That alone may be worth a name change.  Sharon Farrow writes The Berry Basket Mysteries set in Oriole Point, Michigan. The first book in the series, DYING FOR STRAWBERRIES, will be released on November 1, 2016. While this is her debut as ‘Sharon Farrow’, she wrote romance novels under both ‘Sharon Pisacreta’ and ‘Cynthia Kirk’. In 2013, she took on another pseudonym as one half of the writing duo, ‘D.E. Ireland’, the Agatha Award nominated authors of the Eliza Doolittle/Henry Higgins mystery series. I'm joined on my blog today by Amy Shojai, author of the recently released Show and Tell. Because Amy is an expert on pet care and animal behavior and writes dog-viewpoint thrillers, I asked her to speak about what she had learned about writing pets into fiction.  I love reading stories that incorporate animals in a believable fashion, but far too many authors insert pet characters for the wrong reason—or fail to execute in a believable fashion. Reading fiction is all about a suspension of disbelief, and a large percentage of avid readers also love pets. About 65 percent of US Households have a pet—that’s a lot of potential book buyers! The trick, of course, is making your “talking cat” or “thinking dog” so natural that readers accept this ability as fact within your story world. The really avid pet parents already have opinions and insight into how cats and dogs act, and aren’t forgiving of missed paw-steps. PETS AS PROPS. Writers often give the hero a pet to make them more likable, or they’ll have the villain kill an animal to illustrate an unsympathetic character. Most pet-loving readers object to critter-killing simply for shock value. When pets appear in the first chapter and last, with no mention in between, pet lovers recognize this as artificial manipulation. When your hero’s call to action leaves the cat/dog alone at home for weeks, readers wonder why the house isn’t full of crappiocca and hissed-off pets when s/he returns. Please, for the love of doG (and cat), create a character’s relationship with the pet, which builds character depth and reader engagement. TALKING PETS. How your animal characters interact with the humans depends a great deal on the genre and what readers expect. Fantasy’s shape-shifters certainly may have all kinds of critters thinking and speaking the same as the human characters, and many children’s books use anthropomorphized characters to advantage. Based on your story, genre, and reader expectations, decide whether your animals will be “humans in fur coats” or true to their species. Mysteries today are full of talking dogs and cats, and the successful series make clear that these critters have both species-appropriate “extra” skills and limitations. In my September Day series, service dog Shadow has his own viewpoint chapters. He never says a word, yet speaks volumes. GOALS & REWARDS. When creating an animal viewpoint character, go beyond the gift of speech or tail semaphore. Just as your hero and villain require opposing story goals and motivations to fuel the plot, give your pet character reasons to care. Shadow’s story goal and motivation is quite different than his human partner September, and he’s able to offer an enriched reader experience through his enhanced senses. Because of my background as a certified animal behavior consultant, I wanted Shadow to act and react, communicate and feel emotion in a true reflection of the canine species I know (with a bit of fiction speculation). For me, that’s not just a plot device but shows respect for these unique creatures. Shadow has his own character arc in each book. He is not the same clueless nine-month-old puppy that began the series, and has grown and developed alongside his human partner September with each new story. One caution: when writing a series, be aware of the timeline, because pets age much more quickly than human characters. I don’t what Shadow to “age out” of the series too quickly, so the first book LOST AND FOUND happens at Thanksgiving, the second one HIDE AND SEEK follows at Christmas, and now SHOW AND TELL takes place right after Valentine’s Day. Today, pets are considered to be members of the family, in some cases surrogate children. People read for entertainment, for the spills and thrills and tug-at-the-heart rooting for the underdog human—or pet. So adding a furry character to a book, when done well, enhances the reader experiences and gives everyone an extra emotional tug. September and Shadow have just begun their life together, and have many more adventures to come!  Amy Shojai is a nationally known authority on pet care and behavior, a certified animal behavior consultant, a spokesperson for the pet products industry, and the author of 30+ nonfiction pet books. She also writes THRILLERS WITH BITE! which includes the dog-viewpoint thrillers LOST AND FOUND, HIDE AND SEEK, and SHOW AND TELL. Amy can be found on Facebook http://www.facebook.com/amyshojai.cabc, on Twitter @amyshojai, and on Pinterest @amyshojai. Check out her website at http://www.shojai.com.  When I first began to conceive of A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET (to be released April 12, 2016!), an image came to me that ultimately informed the entire novel. That image was of a young woman, barefoot and clad only in her shift, stumbling at dawn through the rubble left by the Great Fire of 1666 (and yes, I am counting down to the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire! See counter to the right!) And, of course, I needed her to run into Lucy, so that my intrepid chambermaid-turned-printer's apprentice would have a reason to be involved in the mystery that follows. But it took me a while to figure out exactly where this encounter could reasonably occur. I thought at first the woman could be found on London Bridge. And I really wanted to write something about how the impaled heads of traitors, which lined either side of the Bridge, had caught fire. After all, in Annus Mirabilis Dryden had described in macabre detail how sparks had scorched the heads: "The ghosts of traitors from the Bridge descend, But then when I did a little more digging, I discovered that London Bridge had been damaged in the Fire, and really was not much of a thoroughfare in the months that followed the blaze. Indeed, there would have been no good reason for Lucy to be traveling in that direction, particularly so early in the morning. So I realized that, first, I needed to think through what Lucy was doing out of Master Aubrey's house, just before dawn. Not too hard to figure out actually. She needed to be delivering books. But then the question became, in what direction did she need to travel to deliver those books? Most people were living to the west of where the Fire had stopped. So why would she be going into the wasteland at all? To figure out this challenge, I began to systematically create a large scale map of Lucy's London using photocopies of reconstructed maps of the period. As I marked in red the burnt out area of London, I realized that the Fire line had been stopped to the west along the River Fleet. The River Fleet? This was not a river I knew anything about. A vague recollection that the Romans had used the river to transport goods, but I couldn't remember ever hearing about it otherwise. I became even more curious when I saw that several bridges, including the Fleet Bridge and Holborn Bridge, crossed it. Clearly, the river was wide enough or significant enough to require actual bridges, so it couldn't just be a stream. Intrigued, I began to read more about this mysterious river. From the maps I could see that the river flowed from the north, went through the Smithfield butcher markets, traversed Fleet Street, and emptied into the Thames. There was also a region that surrounded it, awesomely called "Fleet Ditch." [Sidenote: I really wanted my book to be called "Murder at Fleet Ditch," but that title didn't even make it past my editor. A little too stark, I guess.]  By all accounts, by the 17th century, the River Fleet was no longer a river where boats could easily travel, but had instead become a place where people would dump animal parts, excrement, and general household waste. Indeed, Walter George Bill, one of the great original historians of the Great Fire, described the River Fleet as an "uncovered sewer of outrageous filthiness." And yet, there were still accounts of people bathing in its waters (yuck) and even drinking from it (yuck, yuck, double yuck), despite its considerable stench and grossness.  So the River Fleet--and the original bridges that crossed it--formed a natural backdrop for my story. I could not find a picture of the 17th century Holborn Bridge, but I thought this artist's rendering of Fleet Bridge might serve as a model. And because the Holborn Bridge was still in place after the Fire, with the unburnt area and markets on one side, and the burnt out area on the other, it became the perfect place for Lucy to encounter this desperate woman.  My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... My friend Greg at modern Holborn Bridge... But of course, I was still curious...is there still a River Fleet? The answer is, yes, of course, but it was finally bricked over in the 1730s, after being declared a public menace. It was still problematic though, particularly in the 19th century, when a great explosion occurred as a result of the expanding gasses in the pipes below the streets. Raw sewage apparently spilled everywhere!!! (Don't even think I wouldn't use that awesome detail if I ever set a book in 19th century London. But I doubt it would make it to the cover!) And if you want to know more, here is a nice overview of the history of the River Fleet in all its--ahem--glory. I'm always interested in the process of world-building. While world-building is important for any story, I think that it is even more critical when writers are creating an unfamiliar world for their readers. So, for example, my books are set in 17th century England, during the time of the plague and the Great Fire of London (check out my countdown to the right!!!). While many people know about the Tudor England or the Regency period, the 1660s are a far less familiar period. So, I spend a lot of time thinking about larger cultural, social, political and gender trends that helped define my world, as well as norms, conventions and features of the period. But I think world-building is also important for those setting their books in the future, by nature an undefined period. So I invited author H.A. Raynes onto my blog today to talk about how she went about conceiving and building the future for her debut novel, NATION OF ENEMIES.  Nation of Enemies is set in the near future world of 2032 in the United States. People ask me why that year, in particular, and how did I go about creating that future world? First, the choice to set the story in 2032. Integral to the plot is a presidential election, so that was key in determining the year. Next, and importantly, I wanted it to be near enough that we can almost feel it...imagine it. It’s in our lifetime, depending on our age. I didn’t want to get caught up in the technological advances which would put Nation of Enemies more in the sci-fi realm, which would make it a different book entirely. And so then came the research. In this world I built, the United States is war-torn, like any war-torn country, wrecked by attacks, non-functioning in many ways. People have left the cities, which are easy targets, and fled either to the countryside or else attempt to emigrate to safer shores. They’re less concerned with technology and comfort and more concerned about the safety of their families. As the economy fails, government spending goes toward fighting the war and maintaining hospitals that are on the front line. A doctor is one of my protagonists and for his point of view, I researched the future of medicine. Genetics, equipment, medicine. How a hospital might function with advances in these areas. I interviewed a friend who is a doctor and used the internet at length. Of course, there’s reality and predictions of what will be in the future. I combined those elements with my imagination. I also combined them with the politics of war when I introduced the legislation of the MedID biochip citizens are forced to wear in 2032. There is an actual biochip in use today, though it is quite simple in comparison to my MedID and how it’s been manipulated by the U.S. government. There’s freedom in creating a future world. I also considered schools - what would happen if schools became even more of a target than they are today? (Though just this week, several schools in my state of Massachusetts had bomb threats.) Knowing that parents are vulnerable, I imagined terrorists using schools to, well, terrorize society on a whole new, emotional level. That forced me to bring all schools online in 2032. Kids attend class virtually, creating a safer but less social educational experience. But children suffer in this way, locked in their bedroom away from friends and situations that foster personal growth. Finally, I researched the future of the internet, the language used by experts in the field, and the hackers who exist in a darker but very real realm. It was both fascinating and frightening to discover the skills of these hackers and how they challenge governments and corporations on a daily basis for their own agendas. To “futurize” my novel, though I used terminology hackers currently use along with society’s (and government’s) fears about their power, I simply ushered them down the path. As firewalls and encryptions become more sophisticated, so do hackers. Already we are experiencing hacks into financial institutions and government agencies - I found it easy to imagine an even more widespread problem, especially when the country is distracted by war. I don’t want to spoil any plot points in Nation of Enemies, but recently there was an aspect of the Paris Attacks that included an element I used (researched and pushed farther) in terrorist communications. It sent a chill up my spine. My near-future world of 2032 is not one in which I want to live. I’m a hopeful, positive person and I have great hopes for the futures of my children. Sadly, it wasn’t difficult and in fact was quite plausible to imagine the darker side of humanity emerging with the state of the world we live in today. Let’s hope my imagination does not win out. Doesn't this book sound great?! Here's the official blurb: 2032. Turned away by London Immigration because of his family’s inferior DNA, Dr. Cole Fitzgerald returns to work at Boston’s Mass General hospital. He purchases ballistics skins for family, a bulletproof car and a house in a Safe District. As the War at Home escalates, Cole begins an underground revolution to restore civil liberties and wipe away the inequity of biology. Along the way he’ll risk his family, his career and his life when he discovers the U.S. government may pose a greater threat than the terrorists themselves.  H.A. Raynes was inspired to write NATION OF ENEMIES by a family member who was a Titanic survivor and another who escaped Poland in World War II. Combining lessons from the past with a healthy fear of the modern landscape, this novel was born. A longtime member of Boston’s writing community, she was a finalist in the Massachusetts Screenwriting Competition and has published a short story in the online magazine REDIVIDER. H.A. Raynes has a history of trying anything once (acting, diving out of a plane, white water rafting, and parenting). Writing and raising children seem to have stuck.  I've been waiting for 2016 for a while. Since the Great Fire of London serves as the backdrop for my Lucy Campion mysteries, I decided I wanted to personally commemorate the 350th anniversary of the event here on my blog. And what better way than a countdown?! Check out my nifty calendar to the right! What is interesting, of course, is that the Fire was commonly understood to have begun on September 2, 1666 around 2 am.  Yet, as I have pointed out elsewhere, that was according to the Julian calendar. In France, where they used the same Gregorian calendar that we use today, the tragedy actually occurred on September 12, 1666. So confusing!  I'll talk about some of the other aspects of the Fire in future posts, (including 1666 as the "Devil's Year") but I thought for now, I'd offer the first-hand description from diarist Samuel Pepys. Personally I'm always struck by the calm way he describes the events, particularly in the first passage: "Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today, Jane called up about three in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City. So I rose, and slipped on my night-gown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back side of Mark Lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off, and so went to bed again, and to sleep. . . . By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down tonight by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish Street, by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently, and walked to the Tower; and there got up upon one of the high places, . . .and there I did see the houses at the end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side . . . of the bridge. . . . So down [I went], with my heart full of trouble, to the Lieutenant of the Tower, who tells me that it began this morning in the King's baker's house in Pudding Lane, and that it hath burned St. Magnus's Church and most part of Fish Street already. So I rode down to the waterside, . . . and there saw a lamentable fire. . . . Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that lay off; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies, till they some of them burned their wings and fell down. Having stayed, and in an hour's time seen the fire rage every way, and nobody to my sight endeavouring to quench it, . . . I [went next] to Whitehall (with a gentleman with me, who desired to go off from the Tower to see the fire in my boat); and there up to the King's closet in the Chapel, where people came about me, and I did give them an account [that]dismayed them all, and the word was carried into the King. so I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of York what I saw; and that unless His Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him, and command him to spare no houses. . . [I hurried] to [St.] Paul's; and there walked along Watling Street, as well as I could, every creature coming away laden with goods to save and, here and there, sick people carried away in beds. Extraordinary goods carried in carts and on backs. At last [I] met my Lord Mayor in Cannon Street, like a man spent, with a [handkerchief] about his neck. To the King's message he cried, like a fainting woman, 'Lord, what can I do? I am spent: people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.' . . . So he left me, and I him, and walked home; seeing people all distracted, and no manner of means used to quench the fire. The houses, too, so very thick thereabouts, and full of matter for burning, as pitch and tar, in Thames Street; and warehouses of oil and wines and brandy and other things.  I'm delighted to be joined today by D.M. Pirrone, author of the Hanley & Rivka mystery series (Allium Press). From the official blurb: On a spring morning in 1872, former Civil War captain Ben Champion is found dead in his Chicago bedroom, a bayonet protruding from his back. His death uncovers hidden truths best left buried, that still threaten powerful men. Defective guns sold to the Union army, an 1864 conspiracy to turn Chicago into the capital of a Northwest Confederacy, a former slave passing for white, an escaped Confederate guerrilla bent on revenge...any of these might have led to Champion's murder. Hanley and Rivka race to solve the crime before the secrets of bygone days claim more victims.  D.M.Pirrone D.M.Pirrone As writers of historical fiction, we must still relate to our readers today. What are some of the things from “back then” in your books that have resonance here and now? Corruption, in politics and law enforcement, comes immediately to mind, of course. I’m writing about Chicago in the 1870s, so that’s a no-brainer! Poor Frank Hanley, my Irish detective, is one of the few honest guys in a system that rewards those who go along to get along—he has to deal with bought politicians and corrupt fellow cops who are either just as bad as the “bad guys” or too willing to turn a blind eye. In both of the Hanley & Rivka mysteries so far (Shall We Not Revenge and For You Were Strangers), Hanley has run-ins with a particularly dirty superior officer, Captain Michael Hickey. Hickey was a real person in the Chicago Police Department, and well known for crooked dealing, but no one could ever prove anything. He kept getting kicked upstairs rather than drummed out of the force, which poses an interesting problem—I would love to have Hanley take Hickey down, but history says I can’t. At least, not exactly… Another thing that resonates is injustice against the poor, masquerading as morality. This is a major theme of Shall We Not Revenge, which takes place just after the Great Chicago Fire. Contributions to the stricken city—money, food, clothes, blankets, even books for the library we didn’t have!—were sent from around the world, but distribution of aid was taken from the City Council and given to the Relief and Aid Society, a private organization run by prominent businessmen. These guys set up a system of what was then called “scientific charity”—meaning, a way of making sure aid went only to the so-called deserving poor, and even that, for the briefest possible time. The Aid Society sent out legions of volunteers, many of them well-off society women, to interview those who applied for aid, and decide on the basis of a single visit whether or not each person or family was morally worthy of help.

Did these people really need aid, or were they lying malingerers? Would they use the assistance given them to get back on their feet, or simply mooch off the public? The assumption was that the poor were mostly moochers by nature, the “47 percent” of their day, who didn’t want to work or improve themselves. Giving them aid only encouraged their natural sloth—particularly the Irish, who were seen as lazy drunkards and (as Catholics, mainly) inherently unable to assimilate into Protestant America. Sound familiar? Hanley has to deal with this directly, when his mother requests aid funds to buy a new sewing machine so she can earn a living again as a seamstress. It shocked me to learn that the Relief and Aid Society kept $600,000 worth of aid, smugly confident that they’d reached all the “truly needy” cases in Chicago with only a small portion of the donations sent to the city. For You Were Strangers takes on another hot-button current issue—racial and ethnic divisions, and the whole question of who “belongs” or doesn’t. Not to give too much away, but Rivka Kelmansky’s brother Aaron—who left home ten years earlier to fight in the Civil War, and wasn’t heard from after it ended—turns up on Rivka’s doorstep with a mulatto wife and stepson. He’s been on a long, strange trip, and is seeking sanctuary from danger for himself and his Christian family members among the observant Jewish community he left so long ago. Another character in the book is passing for white, and is forced by events to come to terms with that. There’s also a major character from the South, formerly wealthy and pampered, whose world turned upside down when war came, and who doesn’t succeed very well at finding a new place to belong, with ultimately tragic consequences. So it’s a rich stew of issues that mattered back then as much as they do now.  1677 Wing / 1528:11 1677 Wing / 1528:11 "Where do you get your ideas?" I don't know what it is about this question that drives some writers bonkers, but it's one we all get at book talks and literary events. In response, some authors take the humorous approach ("In Aisle Twelve"), and others try to ignore the question outright ("Next!") Some will roll their eyes and joke about banning the question before offering their response. Personally, I never really understood the reluctance because I love answering this question. I find it so much fun to tell people about the murder ballads that inspired my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. I wonder sometimes whether the real question is not "Where did you get your ideas?" but really, "Where did you get your questions?" Because at the heart of all my books are questions I'm trying to answer, and I suspect this is the same for many authors, perhaps particularly those who write crime fiction. Indeed, I get a lot of my ideas--and questions-- simply by poking around the Early English Books Online. For example, I've been thinking a lot about poisons lately--because, you know, writer--and I came across this gem. The story from 1677 pretty much writes itself! "Horrid News from St. Martins: Or, Unheard of Murder and Poyson. Being a true relation how a girl not full Sixteen years of age murdered her own mother at one time, and a servant-maid at another time with ratsbane. As also, how she very lately gave poyson to two gentlewomen that since met her Mother's Death kept and maintained her. Upon which being apprehended, she has confessed the former villanies, and was on Tuesday last the 19th of this instant June, committed to Prison, where she now remain."  What a great story, right? A sixteen-year old serial killer poisoning the women closest to her? What's up with that? And with ratsbane? That's not an easy way to go either... So of course I have lots of questions... This story may not make it into one of my novels, or who knows? It could be the crux of the whole tale. But the point is, ideas don't come fully formed, they come in bits and pieces. The important thing is what we do with those ideas--the questions we ask when we ponder different ideas. It's not just whodunnit--its all the other questions that drive the story forward. I think, ultimately, that the idea is not a story until the writer learns to get beyond the "What happened?" and begins to ask "Why?" But what do you think? |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed