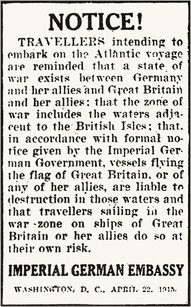

The Tranformative 1910s--a lesser known era. A guest post by debut novelist Radha Vatsal...6/13/2016  I invited debut novelist Radha Vatsal on my blog today, to share how she came to pick the 1910s as the backdrop for her Kitty Weeks historical mysteries. Now that I've got a little summer reading time ahead of me, I'm definitely looking forward to diving into this new series....I think Kitty and Lucy, my printer's apprentice, would have enjoyed hanging out!!!  1915 Warning from German Embassy 1915 Warning from German Embassy The first season of Downton Abbey ends in August 1914 with Lord Grantham announcing at a country party that World War I has begun. (Or rather, that England was at war with Germany—since no one knew just yet what kind of war it would become.) While we tend to associate World War I with Europe and think that America’s involvement in it was short-lived and only began when the US joined the fighting in 1917, life in the United States changed dramatically between 1914-1918, which is why it seemed a perfect era in which to set a mystery series. I find that so many people know about the “Gilded Age,” the period from about the 1870s to the 1900s with its fabulous wealth and “Robber Baron” businessmen. Through novels like The Great Gatsby, we’re also very familiar with the 1920s Jazz Era. But the period in between, the 1910s, remain largely uncharted in popular fiction and film—and so much happened then. The US went from a second-tier nation to the economically most powerful and culturally dominant country in the world. Women went from second-class citizens to finally winning the right to vote. Much of what we associate with modern life—cars, movies, even national boundaries—took their current form during that period. It was a transformative moment in history, which is why I explore it through the eyes of the protagonist of A Front Page Affair, Capability “Kitty” Weeks, a young woman journalist based in New York City. A Front Page Affair, the first in the Kitty Weeks mystery series, takes place during the summer of 1915, in the aftermath of the sinking of the Lusitania and an attack on financier, J.P. Morgan. As the series unfolds, Kitty will confront the many social and political changes taking place in America in the course of her investigations.  Radha Vatsal grew up in Mumbai, India, and came to the United States to attend boarding school when she was sixteen. She has stayed here ever since. Her fascination with the 1910s began when she studied women filmmakers and action-film heroines of silent cinema at Duke University, where she earned her Ph.D. from the English Department. A Front Page Affair is her first novel. You can email her directly at: radhavatsalauthor (at) gmail (dot) com. You can also connect with her on Tumblr, Facebook and Goodreads

0 Comments

1677 Wing / 1528:11 1677 Wing / 1528:11 "Where do you get your ideas?" I don't know what it is about this question that drives some writers bonkers, but it's one we all get at book talks and literary events. In response, some authors take the humorous approach ("In Aisle Twelve"), and others try to ignore the question outright ("Next!") Some will roll their eyes and joke about banning the question before offering their response. Personally, I never really understood the reluctance because I love answering this question. I find it so much fun to tell people about the murder ballads that inspired my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. I wonder sometimes whether the real question is not "Where did you get your ideas?" but really, "Where did you get your questions?" Because at the heart of all my books are questions I'm trying to answer, and I suspect this is the same for many authors, perhaps particularly those who write crime fiction. Indeed, I get a lot of my ideas--and questions-- simply by poking around the Early English Books Online. For example, I've been thinking a lot about poisons lately--because, you know, writer--and I came across this gem. The story from 1677 pretty much writes itself! "Horrid News from St. Martins: Or, Unheard of Murder and Poyson. Being a true relation how a girl not full Sixteen years of age murdered her own mother at one time, and a servant-maid at another time with ratsbane. As also, how she very lately gave poyson to two gentlewomen that since met her Mother's Death kept and maintained her. Upon which being apprehended, she has confessed the former villanies, and was on Tuesday last the 19th of this instant June, committed to Prison, where she now remain."  What a great story, right? A sixteen-year old serial killer poisoning the women closest to her? What's up with that? And with ratsbane? That's not an easy way to go either... So of course I have lots of questions... This story may not make it into one of my novels, or who knows? It could be the crux of the whole tale. But the point is, ideas don't come fully formed, they come in bits and pieces. The important thing is what we do with those ideas--the questions we ask when we ponder different ideas. It's not just whodunnit--its all the other questions that drive the story forward. I think, ultimately, that the idea is not a story until the writer learns to get beyond the "What happened?" and begins to ask "Why?" But what do you think?  I'm so happy and honored to say that my third historical novel, The Masque of a Murderer, officially launches today, April 14! And while I may not be quite as giddy when my first novel, A Murder at Rosamund's Gate (2013) launched two years ago--because nothing can ever compare to the release of a first novel--I'm still as loopy as I was last year, when From the Charred Remains (2014) entered the world. Recently, in preparation for the launch, I've been answering a lot of fun and interesting questions about The Masque of a Murderer (the historical background, the story and characters, and my writing process etc). So, I thought I'd do a quick round-up here! I welcome you to:

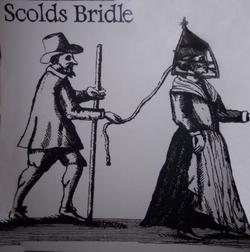

Thanks so much for sharing this journey with me!!! And I appreciate all the bloggers and reviewers who hosted me, including those through Amy Bruno's Historical Fiction Virtual Blog Tours! And I'm always so grateful to the wonderful people at Minotaur, especially Kelley Ragland and Elizabeth Lacks, and my agent David Hale Smith, and of course my wonderful alpha reader, Matt Kelley!! (and now, I turn my attention back to A DEATH ALONG THE RIVER FLEET, due out April 2016!!!!)  The scolding wife Date: 1670-1696 Tract Supplement / A2:4[78] The scolding wife Date: 1670-1696 Tract Supplement / A2:4[78] I won't say HOW exactly, but a scold's bridle features prominently in my third novel, Masque of a Murderer. (Well, okay, maybe one is found on the corpse of a young woman. Or not.) But the bridle does play an important role, and I thought I would give a little more background. Since at least the Middle Ages, women had been expected to heed Paul's admonition to be "chaste, silent and obedient," an expectation that became even more pronounced for women in early modern Europe. Women were branded "scolds" if they harangued their husbands or neighbors, or as we may say today, spoke their minds. "The Scolding Wife," shown here, is one of many tales of a merry young man who made the mistake of marrying a rich widow who very quickly made his life miserable. Indeed, the couple couldn't even sit down to eat without her scolding him: "They was not all at supper set, or at the board sat down, Such accounts explain how the men's good will and cheer are sapped by the woman's speech. It should be noted, however, that the tale is to be 'set to a pleasant tune.' The ballad is meant to be lighthearted--an everyday tale of a man who cannot control his wife. As such, it is as much a comment about his nature as it is about hers. Nevertheless, there is a gendered warning here about the respective roles that men and women should play in a marriage. My favorite of these little discourses is one by Anonymous (1684): "The tongue combatants, or A sharp dispute between a comical courageous country grasier, and a London bull-feather'd butchers twitling, twatling, turbulent, thundering, tempestuous, terrifying, taunting, troublesome, talkative tongu'd wife." Hmmmm.....  Sometimes, however, the warning against women's scolding was more explicit--and more terrifying. Devices known as scold's bridles, or scold's masks, first emerged in the Middle Ages, and continued to be used (in England at least) throughout the early modern era. The scold's mask was a painful contraption of iron and leather that fit over a woman's face that effectively prohibited her from speaking. Sometimes, the woman might be paraded about, as a humiliating reminder to keep her opinions to herself, and as a lesson to other women who might be inclined to do the same. So how does this play out in my novel? Find out in April 2015, when Masque of a Murderer is released! Oh, yes! It's exactly what you think. Read on! Naturally, the subtitle says it all... “Giving An Account of an Old Miserable Woman, who lately kept a blind ale-house, in St. Tooley-Streat, near the Burrough of Southwark; who was so wretchedly covetous, as to deny her self the common benefits of life, as to meat and cloaths; leaving, at her death, about fifteen hundred pounds, to her cat, using to say often, when the cat mow’d: “Peace Puss, peace: The poem that ensues is a bit silly but sort of endearing as well. (And I have to say, it was nice to see a relationship between a woman and her cat that was not wrapped in accusations of witchcraft, bestiality or other fantastical conjectures.) As the story goes, for years, this "mean" woman did not spend her money, preferring to keep her alehouse earnings to herself. Finally, when no one had seen her for a while, one of her neighbors went in to check on her: “Upstairs he went, and in the bed, He found the Rich Old Woman dead: And, looking in a truk just by, Near Eighteen Hundred Pounds did lie. No sooner he had found the hoard, But he divulg’d it all abroad: Then shockt the neighbours, to behold, The Treasur’d bags of coyned gold. Thus did she cheat the battle such, They thought her poor; for she was rich: Her belly saved it for her CAT, But Puss must shew the will for that." Unfortunately, there's no word on what the cat did with her legacy, but hopefully she was able to get a nice mouse cobbler from time to time.

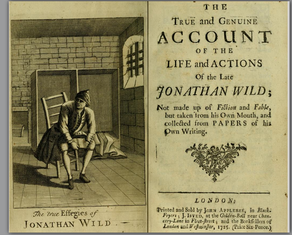

Not crazy though, right?  Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] Anon., Newgate's garland (1724) (Wing C17:1[219b] I started writing a post about murder ballads (which I've discussed on my blog before), to share specific examples about how crime was both a source of entertainment and news in early modern England. At random I selected a ballad to discuss, mainly for the gallows humor embedded in the title: "Newgate's Garland: Being a New Ballad shewing How Mr. Jonathon Wild's throat was cut, from ear to ear, with a penknife by Mr. Blake, alias Blueskin, the bold highwayman, as he stood at his trial at the Old Bailey."  the "newgate garland" may not be this festive the "newgate garland" may not be this festive A garland can refer to a miscellany, or a collection of literary works--so this ballad may have been one of several in a collection. But 'garland' also refers to a strand of material or wreath of flowers, usually hung in celebration. So I can only imagine there was a garland of sort that appeared when poor Mr. Wild's throat was slit "from ear to ear." Clearly there is a sense of celebration throughout this ballad, as the first stanza indicates: "Ye fellows of Newgate, whose fingers are nice, in diving in pockets, or cogging of dice, Ye Sharpers so rich, who can buy off the noose, Ye honester poor rogues, who die in your shoes, Attend and draw near, Good news ye shall hear, How Jonathan's throat was cut from ear to ear, How Blueskin's sharp penknife shall set you at ease, and every man round near me, may rob if they please."  But why would slitting Mr. Wild's throat be a cause for celebration? I began to wonder who Mr. Wild was. So I looked for additional ballads and pamphlets that may explain why Blueskin, that noted highwayman, had sought to murder him. That's when I found another ballad, this one titled: "Jonathan Wild's final fairwell to the world." This would seem more promising. Yet I noticed right away that this ballad was dated in 1725, a full year after the other ballad. Moreover, this ballad described how Jonathan Wild was executed at Tyburn Tree, not murdered at all. Certainly, there was no mention of the throat-slashing incident. So a little MORE digging revealed a fascinating story... As it turns out, Mr. Jonathan Wild was quite famous. After being arrested for debt in 1710, he was thrown into prison. During this time, he began to play two sides of the justice system. In a highly corrupt prison system, Wild first began to do small tasks for the jailers, to a point where he was even trusted to leave the prison to run errands. After a short time, he became a "thief-taker," which was akin to a bounty-hunter in this period before the establishment of a systematic police force. Great Britain's Privy Council even consulted with him on the best way to reduce crime in the country. His answer, not surprisingly, was to raise the reward given to thief-takers from forty pounds per criminal, to a hundred pounds each. Yet, even as he publicly brought criminals to justice--by some accounts, he brought nearly fifty criminals to justice--he was also running a large criminal operation of his own. Wild did very well for himself for quite some time, but his luck turned sour when he was caught helping some of his men break out of prison. Brought to trial, he was mocked roundly by thieves. It was at this point that Blueskin took that near-fatal swipe at him. That part of the ballad makes a little more sense now: "When to the Old-Bailey this Blueskin was led, He held up his Head, his indictment was read, For full forty pounds was the price of his blood. Then hopeless of life, He drew his Penknife, And made a sad widow of Jonathan's wife, But forty pounds paid her, her grief shall appease, and every man round me, may rob if they please.  Wild was in jail for some time, until he was finally brought to the Tyburn Tree for hanging. People were so eager to see him executed that they waited for hours before he arrived. Along the way, Wild was subject to great physical and mental abuse, even having rotting animals and feces thrown upon him as he was carted towards his hanging. He seems to have been dazed and disoriented by the time he emerged from the cart. After he died, apparently his body was stolen, illegally dissected by surgeons, and ended up on display at the Hunterian Museum in London. Already famous before his death, Jonathan Wild became further immortalized when Daniel Defoe wrote about his exploits and sojourn into organized crime. Later, the novelist Henry Fielding--who as a young man was among the spectators of Wild's execution--parodied the man's life and death in the fictionalized History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathon Wild the Great (1745). (Check out, too, historian Peter Ackroyd's wonderful discussion of this parody). Who knew that this murder ballad--which actually turned out to be an attempted murder--would have an incredible back story!  Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 Folly in Print, (London, 1667) Wing / 436:03 I had to laugh when I came across this tract by John Raymond, 17th century author of Folly in Print, or A Book of Rymes (1667). Right away, on the first page, he lets the readers know it really isn't his fault if you don't like his book: "Whoever buyes this Book will say, Next, Raymond then explains to his readers that if they believe what the bookseller says (or sings, as was often the case), it's their own fault if they find they don't like the book after all. "... in Books, where for money or exchange, we take our choice, and in our own Election please our selves; Can you imagine if authors could still add this type of caveat emptor today? Madness! But I'm sure there are many authors today--especially those stung by hurtful reviews--who might wish they could say something like this to their readers: I doe not promise for my Book nor say 'tis good, but here's variety and each man (of his own pallat) is the certain judge: You might like my book, you might not. To each her own!

But what do you think? Have you ever felt deceived about a book?  My book started years ago, when I was a graduate student, pouring over 17th century murder ballads. The ballads served as musical 'true accounts' of murderers who wrote letters to their victims, urging them to rendezvous in dark deserted fields. I knew I had to write about these monsters. I drank lots of coffee.  I spent years writing this first book, scene by scene, in little half hour bursts, at coffee shops, on the train, when the kids were sleeping, until one day--in 2010-- I finished. Even my husband--alpha reader extraordinaire--did not know much about the story. "It's set in the seventeenth century," I'd mumble. "A servant gets killed. Another servant tries to figure it out. Stuff like that." But eventually, I asked him and a few other trusted friends to read the book. I revised again, queried, queried, queried, while writing an entirely different book in the interim. In 2011, I got my wonderful agent who quickly connected me to my equally wonderful editor at Minotaur. My journey was no longer an imaginary jaunt; the path to publication was suddenly very real.  In 2012, more changes happened. The title of my book got changed. My publication date got pushed back. My beautiful cover was revealed. Multiple revisions happened. Copy edits made me crazy, but I learned a lot in the process. I had my first public appearance as a novelist ("2 minutes at Bouchercon"). At some point, I received my ARCs. 2013. Months still passed. My book began to be publicized. I reached the 100 Day mark. Another few months passed. My book started to be reviewed. My hardback copy came in the mail. And now...Be still my heart... MY BOOK IS FINALLY HERE!!!!

Thanks to all my colleagues, friends and family--especially my husband--who made this possible!!!!  Date: 1688 Reel position: Wing / 853:61 Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime. To find out more, check out my guest blog over on Criminal Element, found under the excerpt of A Murder at Rosamund's Gate. What's going on here?

You'll have to check out my post on A Bloody Good Read: Where Writers and Readers of Mysteries Talk Shop to find out!!! |

Susanna CalkinsHistorian. Mystery writer. Researcher. Teacher. Occasional blogger. Categories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed